|

Research Ideas and Outcomes :

Research Article

|

|

Corresponding author: Andrey Vyshedskiy (vysha@bu.edu)

Academic editor: Editorial Secretary

Received: 10 May 2022 | Accepted: 23 Jun 2022 | Published: 14 Jul 2022

© 2022 Andrey Vyshedskiy

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Vyshedskiy A (2022) Language evolution is not limited to speech acquisition: a large study of language development in children with language deficits highlights the importance of the voluntary imagination component of language. Research Ideas and Outcomes 8: e86401. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.8.e86401

|

|

Abstract

Did the boy bite the cat or was it the other way around? When processing a sentence with several objects, one has to establish ‘who did what to whom’. When a sentence cannot be interpreted by recalling an image from memory, we rely on the special type of voluntary constructive imagination called Prefrontal synthesis (PFS). PFS is defined as the ability to juxtapose mental visuospatial objects at will. We hypothesised that PFS has fundamental importance for language acquisition. To test this hypothesis, we designed a PFS-targeting intervention and administered it to 6,454 children with language deficiencies (age 2 to 12 years). The results from the three-year-long study demonstrated that children who engaged with the PFS intervention showed 2.2-fold improvement in combinatorial language comprehension compared to children with similar initial evaluations. These findings suggest that language can be improved by training the PFS and exposes the importance of the visuospatial component of language. This manuscript reflects on the experimental findings from the point of view of human language evolution. When used as a proxy for evolutionary language acquisition, the study results suggest a dichotomy of language evolution, with its speech component and its visuospatial component developing in parallel. The study highlights the radical idea that evolutionary acquisition of language was driven primarily by improvements of voluntary imagination rather than by improvements in the speech apparatus.

Keywords

linguistics, comparative cognition, developmental psychology, evolution of imagination, language evolution, human evolution, recursive language, human language, syntactic language, modern language, neurolinguistics, combinatorial language, language-as-thought-system

Prefrontal Synthesis is an essential component of recursive language

Language cannot be equalled with speech alone. An essential component of language is Prefrontal Synthesis (PFS), which is defined as the process of juxtaposing mental visuospatial objects at will. Consider the two sentences: “The lion carries the monkey” and “The monkey carries the lion.” The two sentences use identical words and the same grammatical structure. Appreciating the delight of the first sentence and the absurdity of the second sentence depends on the visualisation of the scene, that is accomplished by the lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) synthesising the mental object of the monkey and the mental object of the lion into a novel picture (hence the name Prefrontal Synthesis or PFS).

The PFS ability is essential to imagine a hybrid object with the head of a lion and body of a human; to predict the outcome of an imaginary event (“The tiger ate the lion. Who is alive?”); to add two two-digit numbers mentally; to imagine yesterday’s football game per friend’s description; and to follow a fairy tale (“…the Shark took a deep breath and, as he breathed, he drank in the Marionette as easily as he would have sucked an egg. Then he swallowed him so fast that Pinocchio, falling down into the body of the fish, lay stunned for a half hour...”) (

Full language comprehension depends on the PFS ability. PFS is necessary for grasping the meaning of sentences with spatial prepositions (e.g. “Put the pen {under|on|behind} the table”), time prepositions (e.g. “Touch your nose {before|after} you touch your ear”), passive verb tense (“The boy was defeated by the girl”) and nested sentences (e.g. “John lives below Mary, who lives below Steve”). Nesting in sentences is also called recursion. For this reason, linguists refer to modern human languages (that rely on PFS) as recursive languages.

The majority of people report actively imagining the scenes when reading a fairy tale, but a small minority (~ 0.8% of population) claim a life-long trait in which visual mental imagery is entirely absent, a condition called aphantasia (

Neurology of recursive language

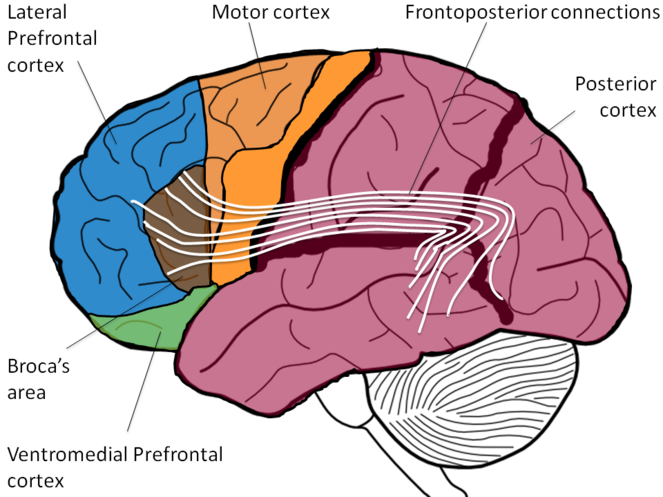

Association of language with Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas is well-known. Less common is the realisation that understanding of the full language depends on the lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC). Wernicke’s area primarily links words with objects (

PFS was hypothesised to be mediated by LPFC-dependent synchronisation of object-encoding neuronal ensembles (

The PFS is a component of voluntary imagination. The word “voluntary” is always associated with activity initiated in and controlled by the frontal cortex. Voluntary muscle contraction is initiated in and controlled by the motor cortex (

A stroke affecting the motor cortex commonly results in paralysis of voluntary movement, but cannot prevent involuntary muscle spasms. A stroke in the LPFC often results in paralysis of voluntary imagination, but does not affect dreaming (

Voluntary imagination includes multiple neurologically distinct components: integration of colour, integration of size, PFS. The time of acquisition of different voluntary imagination components (

Prefrontal synthesis and Chomskyan Merge

Chomskyan Merge (

Neurologically, the Merge operation depends on a broad range of distinct mechanisms. Interpreting a sentence ‘ship sinks,’ can be accomplished via simple memory recall, i.e. by remembering a previously-seen picture of a sinking ship. Memory recall involves activation of a single objectNE in the posterior cortex and only minimally involves the LPFC (

Therefore, it is impossible to describe PFS in terms of the Merge operation. PFS, defined as deliberate visuospatial juxtaposition of mental objects, is mediated by a single neurological mechanism: synchronisation of objectNEs. The Merge operation employs the neurological process of PFS for some functions, but many of the Merge operations rely exclusively on simpler neurological mechanisms: simple recall, categorically-primed spontaneous imagination, integration of modifiers etc. (

Dissociation of PFS and articulate speech in patients with brain damage

Patients with damage to the LPFC (

The “high-speed” connections between the front (marked as Lateral Prefrontal Cortex) and the back of the brain (marked as Posterior Cortex), such as arcuate fasciculus and superior longitudinal fasciculus, mediate voluntary imagination and combinatorial language comprehension. The connections are marked Frontoposterior connections.

There is no established term for ‘PFS paralysis’ in the English-speaking literature. Henry Head, English neurologist, first identified this condition in aphasiacs in 1920 and named it “semantic aphasia” (

Acquisition of PFS in children

Typically developing children acquire PFS between the ages of 3 and 4 years (

Failure to acquire PFS results in a lifelong inability to understand recursive language, including spatial prepositions, time prepositions, fairytales (that require the listener to imagine unrealistic situations) and recursion (here and later, recursion is used to refer to sentence level recursion only as in this example: “John lives below Mary, who lives below Steve”). Amongst individuals diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), the prevalence of lifelong PFS paralysis is 30 to 40% (

Accordingly, ASD children with language deficits could serve as a proxy for early hominins who were not exposed to recursive language (

Voluntary imagination exercises are associated with improvement of combinatorial language in children with autism

We hypothesised that language in ASD children could be significantly improved with voluntary imagination exercises. Accordingly, we developed voluntary imagination exercises, organised them into an application and provided this application to ASD children ages 2 to 12 years (

This application includes both non-verbal and verbal gamified exercises. Non-verbal activities aim to provide voluntary imagination training visually through implicit instructions. For example, a child can be presented with two separate images: that of a train and a window pattern. The task is to mentally integrate the train and the window pattern and to match the result of integration to the picture of the complete train positioned amongst several incorrect trains. The child is encouraged to avoid trial-and-error, focusing instead on integrating separate train parts mentally, thus training voluntary imagination. Different games use various tasks and visual patterns to keep the child engaged. Verbal activities train the same voluntary imagination ability by using higher forms of language, such as noun-adjective combinations, spatial prepositions, recursion and syntax. For example, a child can be instructed to put the cup {behind|in front of|on|under} the table or take animals home following an explanation that the lion lives above the monkey and under the cow. In every activity, a child listens to a short story and then works within an immersive interface to generate an answer. Correct answers are rewarded with pre-recorded encouragement and animations.

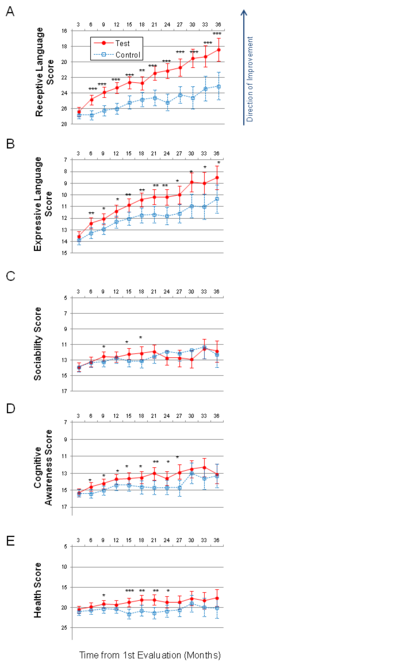

In a 3-year clinical study of 6,454 ASD children, children who engaged with voluntary imagination exercises showed 2.2-fold greater combinatorial language comprehension improvement and 1.4-fold expressive language improvement than children with similar initial evaluations (

Longitudinal plots of subscale scores LS Means. Horizontal axis shows months from the 1st evaluation (0 to 36 months). Error bars set at 95% confidence interval. To facilitate comparison between subscales, all vertical axes ranges have been normalised to show 35% of their corresponding subscale’s maximum available score. A lower score indicates symptoms improvement. P-value is marked: ***< 0.0001; **< 0.001; *< 0.05. (A) Receptive Language score. (B) Expressive Language score. (C) Sociability score. (D) Cognitive awareness score. (E) Health score. The test group included study participants who completed more than one thousand PFS exercises and made no more than one error per exercise. The control group was selected from the rest of participants by a matching procedure. Each test group participant was matched to the control group participant by age, gender, expressive language, receptive language, sociability, cognitive awareness and health score at 1st evaluation using propensity score analysis. The complete methods and the discussion of results can be found in

These findings suggest that language may be improved by training voluntary imagination and exposes the importance of the voluntary imagination in language evolution.

Evolution of voluntary imagination

The LPFC is smaller in apes and the frontoposterior fibres (such as arcuate fasciculus) mediating all aspects of voluntary imagination in humans are much smaller or absent in apes (

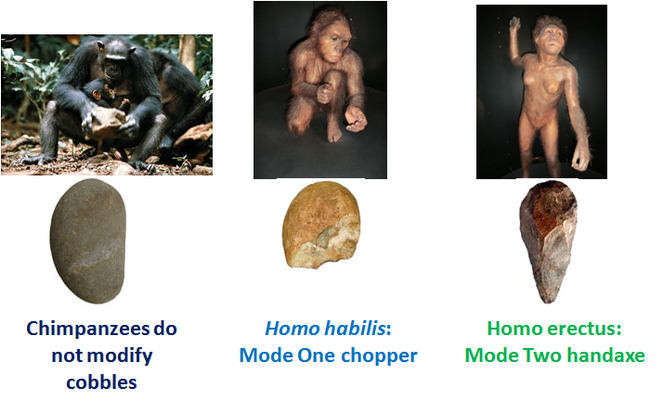

Evolutionary improvement of voluntary imagination can be followed by looking at the stone tools evolution (Fig.

Evolution of stone tool culture. Chimpanzees make use of cobbles to break nuts, but they do not modify them. Homo habilis was one of the earliest hominin species that intentionally modified cobbles to manufacture the crude, Mode One choppers. Homo habilis was only able to break out large flakes from a cobble; its voluntarily control of its mental template was quite crude. Homo erectus, on the other hand, was able to break off much smaller flakes and produce the fine, symmetrical, Mode Two handaxes; therefore, Homo erectus was most likely capable of finer voluntary control of its mental template. (Ape reproductions as photographed by the author at the evolution exhibit the Valladoki Science Museum, Spain.)

Apes do not manufacture stone tools in the wild and attempts to teach stone tools manufacturing to apes have failed (

Speech and voluntary imagination could have been acquired separately

The two components of language – articulate speech and the voluntary imagination – are mediated by different cortical areas and, therefore, it is possible that the two processes have evolved separately. It has been hypothesised that the visuospatial control by the LPFC evolved in response to the predation pressure (

The evolutionary pressure for improvement of the speech apparatus likely came from a different and independent source. Speech apparatus evolution was hypothesised to be the result of hundreds of mutations, each of which incrementally improved articulation ability by enhancing the control of the diaphragm, lips, tongue, chicks, vocal cords, larynx position in the trachea and so on (

When articulate speech mutations originate in a leader, they result in immediate improvement in communication, albeit one-way communication from the leader to tribe members and, consequently, increase tribe’s productivity and the leader’s survival chances. As an alpha male, the leader would have a high number of children and, thus, his “improved vocal apparatus” mutation would have been fixed in a population.

Thus, articulate speech could have developed separately from voluntary imagination: their evolutionary driving forces could have been different and hundreds of mutations associated with improvement of each function could have been independent.

When was speech acquired by hominins?

There is general consensus that articulate speech was acquired from 2 million to 600,000 ya (

- the changes in hyoid bone,

- the flexion of the bones of the skull base,

- increased voluntary control of the muscles of the diaphragm,

- anatomy of external and middle ear and

- the evolution of the FOXP2 gene.

1. The changes in hyoid bone. This small U-shaped bone lies in the front of the neck between the chin and the thyroid cartilage. The hyoid does not contact any other bone. Rather, it is connected by tendons to the musculature of the tongue and the lower jaw above, the larynx below and the epiglottis and pharynx behind. The hyoid aids in tongue movement used for swallowing and sound production. Accordingly, phylogenetic changes in the shape of the hyoid provide information on the evolution of the vocal apparatus.

The hyoid bone of a chimpanzee is very different from that of a modern human (

2. The flexion of the bones of the skull base. Laitman (

3. Increased voluntary control of respiratory muscles. Voluntary cortical control of respiratory muscles is a crucial prerequisite for complex speech production (

4. The anatomy of the external and middle ear. Modern humans show increased sensitivity to sounds between 1 kHz and 6 kHz and particularly between 2 kHz and 4 kHz. Chimpanzees, on the other hand, are not particularly sensitive to sounds in this range (

5. The evolution of the FOXP2 gene. The most convincing evidence for the timing of the acquisition of the modern speech apparatus is provided by DNA analysis. The FOXP2 gene is the first identified gene that, when mutated, causes a specific language deficit in humans. Patients with FOXP2 mutations exhibit great difficulties in controlling their facial movements, as well as with reading, writing, grammar and oral comprehension (

Conclusions on acquisition of articulate speech. Based on these five lines of evidence — the structure of the hyoid bone, the flexion of the bones of the skull base, increased voluntary control of the muscles of the diaphragm, anatomy of external and middle ear and the FOXP2 gene evolution — most paleoanthropologists conclude that the speech apparatus experienced significant development starting with Homo erectus about 2 million ya and that it reached modern or nearly modern configurations in Homo heidelbergensis about 600,000 year ago (

When was prefrontal synthesis acquired?

When was PFS, the most advanced component of voluntary imagination mechanisms, acquired by hominins? Voluntary imagination was improving slowly in our ancestors over the last 3.3 million years as revealed by the changing quality of stone tools (

What artifacts unambiguously signify acquisition of PFS?

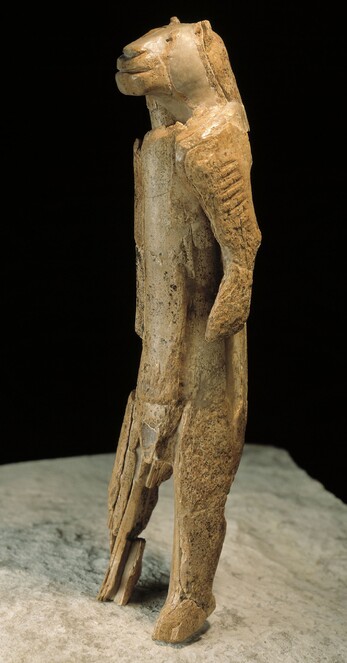

1) Composite figurative arts. Depiction of composite objects that do not exist in nature provides undeniable evidence of PFS. These composite objects must have been imagined by the artists by first mentally synthesising parts of two independent mental objects together and then executing the product of this mental creation in ivory or other material.

2) Bone needles with an eye. Bone needles are used for stitching clothing. To cut and stitch an animal hide into a well-fitting garment, one needs first to mentally simulate the process, i.e. imagine how the parts can be combined into a finished product that fits the body. Such mental simulation is impossible without PFS.

3) Construction of dwellings. An integral part in construction of a dwelling is visual planning, which relies on the mental simulation of all the necessary construction steps, which is impossible without PFS.

4) Religious beliefs. An individual without PFS cannot be induced into believing in spirits, as they cannot understand a description of gods, cyclops, mermaids or any other hybrid creatures. Therefore, religious beliefs and beliefs in the afterlife are the ultimate manifestations of PFS. The origin of religious beliefs can be traced by following the evidence of beliefs in the afterlife. Beliefs in the afterlife, in turn, are thought to be associated with adorned burials. Hence, the development of religious beliefs may be inferred by studying the time period when humans started to bury their deceased in elaborate graves with accompanying “grave goods.”

The PFS hypothesis can be rejected if these four types of artifacts appear in the archaeological record at different times: if composite figurative arts appeared in the archaeological record 100,000 years before bone needles with an eye, that would indicate that their manufacturing is not associated with the same underlying cognitive ability. Conversely, the PFS hypothesis would be strengthened if all four types of artifacts were associated with each other in time and geography. Let us look at the archeological evidence.

1. Composite figurative objects. Multiple composite objects appear in the archaeological record around 40,000 ya. The Lowenmensch (“lion-man”) sculpture excavated from the caves of Lone valley in Germany was dated to 39,000 years ago (

2. Bone needles with an eye. Earliest bone needles are dated to 61,000 years ago (

This time period was also marked by the arrival of bow-and-arrow and musical instruments. The earliest quartz-tipped arrows have been dated to about 64,000 years ago (

3. Construction of dwellings. There is little evidence of hominins constructing dwellings or fire hearths until the arrival of Homo sapiens. While Neanderthals controlled the use of fire, their hearths were usually very simple: most were just shallow depressions in the ground. There is almost a complete lack of evidence of any dwelling construction at this period (

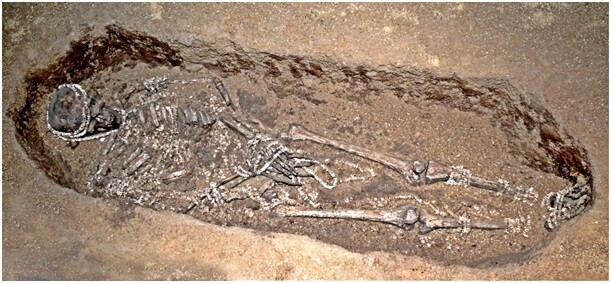

4. Religious beliefs. The oldest known human burial, dated at 500,000 years ago and attributed to Homo heidelbergensis, was found in the Sima de los Huesos site in Atapuerca, Spain and consists of various corpses deposited in a vertical shaft (

Human skeletal remains that were intentionally stained with red ochre were discovered in the Skhul and Qafzeh Caves, in Levant and dated to approximately 100,000 years ago (

The number of known adorned burials and the sophistication of the offerings significantly increased around 40,000 years ago. To date, over one hundred graves of Homo sapiens have been discovered that date back to the period between 42,000 and 20,000 years ago (

An elaborate burial of a 60-year-old found in Sungir, Russia. The man is wearing bracelets, necklaces, pendants and a tunic adorned with thousands of mammoth-ivory beads. Two juvenile burials were found at the same site. The site and the skeletons date back to 30,000 ya (

Conclusions from paleontological evidence. Multiple types of archaeological artifacts unambiguously associated with PFS appear simultaneously around 65,000 ya in multiple geographical locations. This abrupt change in archaeological artifacts’ quality indicating modern imagination has been characterised by paleoanthropologists as the “Upper Paleolithic Revolution” (

Additional evidence of PFS acquisition by humans migrating out of Africa 65,000 ya is provided by a significant change in hunting strategy. Without PFS, one cannot envision the building of an animal trap, for example, pitfall trap, which requires digging a deep pit and camouflaging it with twigs and branches. While Neanderthals hunted large animals, such as mammoths, they were not using traps or stratagem. The high frequency of bone fractures found in Neanderthal skeletons, especially in the ribs, femur, fibulae, spine and skull, suggests that their primary hunting technique has been to use thrusting spears (

Furthermore, trapping large animals must have provided a significant boost to our ancestors’ diet and set their population growth on to an exponential trajectory. In fact, both the extent and the speed of colonisation of the planet by Homo sapiens 70,000 to 65,000 years ago are unprecedented. Our ancestors quickly settled in Europe and Asia and crossed open water to Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean by 65,000 years ago (

Non-recursive communication system in pre-PFS hominids is counter-intuitive

If PFS was acquired around 70,000 ya and articulate speech was acquired before 600,000 ya, there must have been at least half a million year interval when hominins were using non-recursive communication systems. Visualising a pre-PFS hominin from before 70,000 ya is extremely counterintuitive. Students tend to imagine an ape, which has learned several thousand words, gained an ability to generate articulate sounds, acquired control over their impulses and improved their imagination. A better way to visualise a pre-PFS hominin is to imagine a modern human with a LPFC lesion that resulted in PFS paralysis. Waltz et al. has demonstrated that these individuals can perform many voluntary imagination tasks, such as integration of modifier and mental rotation, but fail precipitously in visuospatial and verbal relational questions that require PFS (

Individuals with PFS paralysis (as a result of lesion or a neurodevelopmental condition) do not understand recursive sentences (e.g. “John lives below Mary, who lives below Steve”) and spatial prepositions and, therefore, by definition, use a non-recursive communication system. They provide the best window into the non-recursive communication system of pre-PFS hominins living before 70,000 ya.

The great synergy: marriage of articulate speech and PFS creates modern language

While speech apparatus and voluntary imagination were improving as a result of separate independent evolutionary pressures over several million years, it does not mean that there was no synergy between them. Recent studies demonstrate a clear synergistic relationship between language proficiency and voluntary imagination in children. Deaf individuals communicating through a formal sign language from an early age develop normal voluntary imagination. However, in the absence of early communication or when the sign language is lacking spatial prepositions and recursion, deaf individuals show clear deficits of voluntary imagination. Deaf individuals who had learned American Sign Language (ASL) early in life were found to be more accurate than later learners at identifying whether two complex-shape figures presented at different degrees of rotation were identical or mirror images of each other (

All available experimental evidence from modern-day children suggests the existence of an ontogenetic synergistic relationship between early childhood recursive language use and voluntary imagination skills. It is likely that similar synergy also existed on the phylogenetic level. Improving speech apparatus enabled better visuospatial processing and vice versa. The greatest synergy between articulate speech and voluntary imagination has been achieved with acquisition of PFS. PFS has enabled articulate speech to communicate an infinite number of novel object combinations with the use of a finite number of words, the system of communication that we call recursive language. At the same time, PFS endowed the human mind with the most efficient way to simulate the future in the neocortex: by voluntarily combining and re-combining mental objects from memory. The marriage of articulate speech and voluntary imagination at approximately 70,000 ya resulted in the birth of a practically new species – the modern Homo sapiens, the species with the same creativity and imagination as modern humans.

Improvement of voluntary imagination defined the pace of language evolution

In this manuscript, we have presented multiple theoretical and experimental observations that argue for dissociation of articulate speech and voluntary imagination: 1) The neurological apparatus for articulate speech (the Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas) is distinct from the neurological apparatus for voluntary imagination (the LPFC control over the visual areas in the posterior cortex). 2) Double dissociation of PFS and articulate speech in patients with brain lesions: patients with PFS paralysis do not demonstrate changes in articulate speech and patients with expressive aphasia can have normal PFS. 3) Double dissociation of PFS and articulate speech in childhood language development: some children acquire normal articulate speech while showing clear deficits in voluntary imagination, while others can have trouble in articulate speech, but attain normal PFS. 4) Our recent data from a large group of children with autism demonstrate that children improve their language following a course of voluntary imagination exercises. All these observations point to the dichotomy of recursive language evolution and the importance of the visuospatial component of language.

The dichotomy of recursive language evolution poses a dilemma: which of the two components of language was driving recursive language acquisition in hominins? Since articulate speech is so obviously different between humans and apes, this question has been commonly answered in favour of articulate speech. Charles Darwin wrote in 1871: “I cannot doubt that language owes its origin to the imitation and modification, aided by signs and gestures, of various natural sounds, the voices of other animals, and man’s own instinctive cries” (

In this paper, we propose a radical idea that evolutionary acquisition of recursive language was limited not by the capacities of the speech apparatus, but by the improvement of voluntary imagination (i.e. the gradual progress in the development of the visuospatial control by the LPFC). Voluntary imagination is mediated via some of the longest fibres in the brain (arcuate fasciculus). Fine-tuning of these fibres by experience-dependent myelination is far more complex and slower than acquisition of vocabulary. Typically-developing children commonly acquire articulate speech by 2 years of age, but do not acquire PFS until 4 years of age (

In fact, the argument in favour of the speech apparatus limiting the acquisition of recursive language is fundamentally weak, as speech is not an obligatory component of recursive language at all. If hominins had neurological machinery for voluntary imagination, they could have invented sign language. A sign language does not require hundreds of mutations necessary for an articulate speech apparatus and apes easily learn hundreds of signs (

Additional supporting evidence for this hypothesis comes from the observation of the variety of sound boxes in birds and the uniqueness of human voluntary imagination. Articulate sounds can be generated by Grey parrots and thousands of other songbird species (

On the bases of neurological observations, archaeological findings, children studies, the sign language argument and variety of sound boxes in birds, we argue that the evolution of hominin speech apparatus must have followed (rather than led to) the improvements in voluntary imagination. Contrary to Darwin’s prediction, not speech, but voluntary imagination appears to define the pace of recursive language evolution.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. P. Ilyinskii for careful editing of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- A juvenile early hominin skeleton from Dikika, Ethiopia.Nature443(7109):296‑301. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05047

- Evidence that two main bottleneck events shaped modern human genetic diversity.Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences277(1678):131‑137. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1473

- A Middle Palaeolithic human hyoid bone.Nature338(6218):758‑760. https://doi.org/10.1038/338758a0

- The Sima de los Huesos crania (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). A comparative study.Journal of Human Evolution33:219‑281. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.1997.0133

- Earliest hunting scene in prehistoric art.Nature576(7787):442‑445. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1806-y

- Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa.Journal of Archaeological Science35(6):1566‑1580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.006

- Neural systems engaged by planning: a PET study of the Tower of London task.Neuropsychologia34(6):515‑526. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(95)00133-6

- Assessing the causes of Late Pleistocene extinctions on the continents.Science306(5693):70‑75. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1101476

- Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: indications for modern behavior.Journal of Human Evolution56(3):307‑314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.10.005

- The archaeological framework of the Upper Paleolithic Revolution.Diogenes54(2):3‑18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0392192107076869

- A review of subtyping in autism and proposed dimensional classification model.Journal of Autism and DEvelopmental Disorders31(4):411‑22. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010616719877

- Editorial: The biology of language under a minimalist lens: promises, achievements, and limits.Frontiers in Psychology12https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.654768

- Memory, language and intellectual ability in low-functioning autism.Memory in Autism268‑290. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511490101.016

- 82,000-year-old shell beads from North Africa and implications for the origins of modern human behavior.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences104(24):9964‑9969. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0703877104

- Endurance running and the evolution of Homo.Nature432(7015):345‑352. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03052

- Regional cerebral blood flow throughout the sleep-wake cycle. An H2(15)O PET study.Brain120(7):1173‑1197. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/120.7.1173

- Endocast of Sambungmacan 3 (Sm 3): A new Homo erectus from Indonesia.The Anatomical Record262(4):369‑379. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.1047

- A Homo erectus hyoid bone: possible implications for the origin of the human capability for speech.Collegium antropologicum32(4):1007‑11.

- Lower Pleistocene hominids and artifacts from Atapuerca-TD6 (Spain).Science269(5225):826‑830. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7638598

- On Phases.Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory132‑166. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262062787.003.0007

- The frontopolar cortex and human cognition: Evidence for a rostrocaudal hierarchical organization within the human prefrontal cortex.Psychobiology28(2):168‑186. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03331976

- Changes in cortical activity during mental rotation A mapping study using functional MRI.Brain119(1):89‑100. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/119.1.89

- The Autobiography of Alexander Luria.Psychology Preshttps://doi.org/10.4324/9781315799353

- The Adventures of Pinocchio.

- Neanderthals and Homo sapiens had similar auditory and speech capacities.Nature Ecology & Evolution5(5):609‑615. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01391-6

- Dynamic in-hand movements in adult and young juvenile chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes).American Journal of Physical Anthropology138(3):274‑285. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20925

- Speech naturalness detection and language representation in the dog brain.NeuroImage248https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118811

- Lion man takes pride of place as oldest statue.Naturehttps://doi.org/10.1038/news030901-6

- Micro-biomechanics of the Kebara 2 Hyoid and its implications for speech in Neanderthals.PLoS ONE8(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082261

- The prevalence of aphantasia (imagery weakness) in the general population.Consciousness and Cognition97https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2021.103243

- The Descent of Man and Seletion in Relation to Sex.John Murrayhttps://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.121292

- On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neandertal linguistic capacities and its consequences.Frontiers in Psychology4https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00397

- Encyclopedia of human evolution and prehistory. Routledge.Routledgehttps://doi.org/10.4324/9780203009420

- Nassarius kraussianus shell beads from Blombos Cave: evidence for symbolic behaviour in the Middle Stone Age.Journal of Human Evolution48(1):3‑24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.09.002

- Refusing to imagine? On the possibility of psychogenic aphantasia. A commentary on Zeman et al. (2015).Cortex74:334‑335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2015.06.013

- The third chimpanzee.Oneworld Publications

- Toward a functional neuroanatomy of semantic aphasia: A history and ten new cases.Cortex97:164‑182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2016.09.012

- Fluid intelligence after frontal lobe lesions.Neuropsychologia33(3):261‑268. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(94)00124-8

- Mental Imagery Therapy for Autism (MITA) - An early intervention computerized brain training program for children with ASD.Autism-Open Access05(03). https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7890.1000153

- Children with autism appear to benefit from parent-administered computerized cognitive and language exercises independent of the child’s age or autism severity.Autism-Open Access07(05). https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7890.1000217

- Tablet-based cognitive exercises as an early parent-administered intervention tool for toddlers with autism - evidence from a field study.Clinical Psychiatry03(01). https://doi.org/10.21767/2471-9854.100037

- Visual imagery and visual-spatial language: Enhanced imagery abilities in deaf and hearing ASL signers.Cognition46(2):139‑181. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(93)90017-p

- Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry.American Psychologist34(10):906‑911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.34.10.906

- Epidemiological surveys of pervasive developmental disorders.Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders33‑68. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511544446.003

- Fossil Evidence for the Origin of Speech Sounds.The Origins of Musichttps://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5190.003.0019

- The brain basis of language processing: from structure to function.Physiological Reviews91(4):1357‑1392. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00006.2011

- Overview of prefrontal functions.The Prefrontal Cortex375‑425. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-407815-4.00008-8

- Conceptual size representation in ventral visual cortex.Neuropsychologia81:198‑206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.12.029

- Richness and diversity of burial rituals in the Upper Paleolithic.Diogenes54(2):19‑39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0392192107077649

- Separate visual pathways for perception and action.Trends in Neurosciences15(1):20‑25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(92)90344-8

- Chimpanzees of the Gombe Stream Reserve. In:Primate Behavior: Field Studies of Monkey and Apes.Holt, Rinehart & Winston,425-473pp.

- A complete Neandertal mitochondrial genome sequence determined by high-throughput sequencing.Cell134(3):416‑426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.021

- A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome.Science (New York, N.Y.)328(5979):710‑722. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188021

- The revolution that didn't arrive: A review of Pleistocene Sahul.Journal of Human Evolution55(2):187‑222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.11.006

- Studies on the evolution and function of FoxP2, a gene implicated in human speech and language, using songbirds as a model.Freie Universität Berlinhttps://doi.org/10.17169/refubium-13866

- Sapiens: A brief history of humankind.Harvill Secker London

- 3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya.Nature521(7552):310‑315. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14464

- Man the Hunted. In:Man the Hunted: Primates, Predators, and Human Evolution.Routledgehttps://doi.org/10.4324/9780429499081

- Aphasia and kindred disorders of speech.Brain43(2):87‑165. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/43.2.87

- The organization of behavior: A neuropsychological approach.John Wiley & Sons

- Middle Stone Age shell beads from South Africa.Science304(5669):404‑404. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1095905

- Engraved ochres from the Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa.Journal of Human Evolution57(1):27‑47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.01.005

- Τesting models for the beginnings of the Aurignacian and the advent of figurative art and music: The radiocarbon chronology of Geißenklösterle.Journal of Human Evolution62(6):664‑676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.03.003

- Oscillatory synchronization in large-scale cortical networks predicts perception.Neuron69(2):387‑396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.027

- Dynamically modulated spike correlation in monkey inferior temporal cortex depending on the feature configuration within a whole object.Journal of Neuroscience25(44):10299‑10307. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3036-05.2005

- Geoarchaeology of the Kostenki–Borshchevo sites, Don River Valley, Russia.Geoarchaeology22(2):181‑228. https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.20163

- Desert kites in the Negev desert and northeast Sinai: Their function, chronology and ecology.Journal of Arid Environments74(7):806‑817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2009.12.001

- Striped bodypainting protects against horseflies.Royal Society Open Science6(1). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.181325

- Scales drive detection, attention, and memory of snakes in wild vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus pygerythrus).Primates58(1):121‑129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-016-0562-y

- Why we curse: A neuro-psycho-social theory of speech.John Benjamins Publishinghttps://doi.org/10.1075/z.91

- ‘Behavioral modernity’ as a process, not an event, in the human niche.Time and Mind11(2):163‑183. https://doi.org/10.1080/1751696x.2018.1469230

- The dawn of human culture.Wiley New York

- The Human Career.University of Chicago Presshttps://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226027524.001.0001

- A triple burial from the Upper Paleolithic of Dolní Věstonice, Czechoslovakia.Journal of Human Evolution16:831‑835. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(87)90027-3

- Neural correlates of consciousness: progress and problems.Nature Reviews Neuroscience17(5):307‑321. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.22

- Comparison of auditory functions in the chimpanzee and human.Folia Primatologica55(2):62‑72. https://doi.org/10.1159/000156501

- Hominids without homes: On the nature of Middle Palaeolithic settlement in Europe. In:The Middle Palaeolithic Occupation of Europe.

- The derived FOXP2 variant of modern humans was shared with Neandertals.Current Biology17(21):1908‑1912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.008

- The basicranium of fossil hominids as an indicator of their upper respiratory systems.American Journal of Physical Anthropology51(1):15‑33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330510103

- The basicranium of Plio-Pleistocene hominids as an indicator of their upper respiratory systems.American Journal of Physical Anthropology59(3):323‑343. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330590315

- Advances in understanding the relationship between the skull base and larynx with comments on the origins of speech.Human Evolution3:99‑109. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02436593

- Neural correlates of superior intelligence: Stronger recruitment of posterior parietal cortex.NeuroImage29(2):578‑586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.036

- A motor cortex circuit for motor planning and movement.Nature519(7541):51‑56. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14178

- Quartz-tipped arrows older than 60 ka: further use-trace evidence from Sibudu, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.Journal of Archaeological Science38(8):1918‑1930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2011.04.001

- A Complete skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the evolutionary biology of early Homo.Science342(6156):326‑331. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238484

- Stimulus overselectivity in autism: A review of research.Psychological Bulletin86(6):1236‑1254. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.6.1236

- Traumatic Aphasia.Mouton,The Hague. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110816297

- Higher cortical functions in man.Springer Science & Business Mediahttps://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-8579-4

- Single, rapid coastal settlement of Asia revealed by analysis of complete mitochondrial genomes.Science308(5724):1034‑1036. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1109792

- The evolution of human speech: The role of enhanced breathing control.American Journal of Physical Anthropology109(3):341‑363. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-8644(199907)109:33.0.co;2-2

- The correlation theory of brain function (Internal Report 81-2).Goettingen: Department of Neurobiology, Max Planck.

- A recent evolutionary change affects a regulatory element in the human FOXP2 Gene.Molecular Biology and Evolution30(4):844‑852. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mss271

- Does age of language acquisition affect the relation between American sign language and mental rotation.University of Minnesota

- Age of acquisition effects on mental rotation: Evidence from Nicaraguan sign language. In:BUCLD 37: Proceedings of the 37th Boston University Conference on Language Development.

- Communicative capacities in Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sierra de Atapuerca in Spain.Quaternary International295:94‑101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.07.001

- Language evolution and complexity considerations: The no half-Merge fallacy.PLOS Biology17(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000389

- The Stone Age of Mount Carmel. The Fossil Human Remains from the Levalloiso-Mousterian.Clarendon Press, Oxford

- The Neanderthal Legacy: An Archaeological Perspective from Western Europe.Princeton University Presshttps://doi.org/10.1515/9781400843602

- Dialects in wild chimpanzees?American Journal of Primatology27(4):233‑243. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.1350270402

- Language deficits in schizophrenia and autism as related oscillatory connectomopathies: An evolutionary account.Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews83:742‑764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.029

- Twenty-Seven Years of Project Koko and Michael.All Apes Great and Small165‑176. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47461-1_15

- Vocal learning in Grey parrots: A brief review of perception, production, and cross-species comparisons.Brain and Language115(1):81‑91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2009.11.002

- Direct AMS Radiocarbon dates for the Sungir mid Upper Palaeolithic burials.Antiquity74(284):269‑270. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003598x00059196

- Stimulus overselectivity four decades later: A review of the literature and its implications for current research in Autism spectrum disorder.Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders40(11):1332‑1349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0990-2

- Evidence from an emerging sign language reveals that language supports spatial cognition.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences107(27):12116‑12120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0914044107

- Auditory ossicles from southwest Asian Mousterian sites.Journal of Human Evolution54(3):414‑433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.10.005

- Sparse but not ‘Grandmother-cell’ coding in the medial temporal lobe.Trends in Cognitive Sciences12(3):87‑91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.12.003

- Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia.Nature468(7327):1053‑1060. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09710

- The evolution of the arcuate fasciculus revealed with comparative DTI.Nature Neuroscience11(4):426‑428. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn2072

- Breve nota sobre el hioides Neandertalense de Sidrón (Piloña, Asturias).Barcelona: Edicions Bellaterra

- Perception's shadow: long-distance synchronization of human brain activity.Nature397(6718):430‑433. https://doi.org/10.1038/17120

- Mental rotation and object categorization share a common network of prefrontal and dorsal and ventral regions of posterior cortex.NeuroImage35(3):1264‑1277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.012

- Diagnostic features of autism.Journal of Child Neurology3https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073888003001s11

- Kanzi’s primal language: The cultural initiation of primates into language.Springerhttps://doi.org/10.1057/9780230513389

- Early Middle Stone Age personal ornaments from Bizmoune Cave, Essaouira, Morocco.Science Advances7(39). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abi8620

- A human intracranial study of long-range oscillatory coherence across a frontal–occipital–hippocampal brain network during visual object processing.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences105(11):4399‑4404. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708418105

- 2.5-million-year-old stone tools from Gona, Ethiopia.Nature385(6614):333‑336. https://doi.org/10.1038/385333a0

- Children creating language: how Nicaraguan sign language acquired a spatial grammar.Psychological science12(4):323‑8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00359

- The neural correlates of dreaming.Nature Neuroscience20(6). https://doi.org/10.1101/012443

- Visual feature integration and the temporal correlation hypothesis.Annual Review of Neuroscience18(1):555‑586. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.003011

- Binding by synchrony.Scholarpedia2(12). https://doi.org/10.4249/scholarpedia.1657

- Brain functional and structural predictors of language performance.Cerebral Cortex26(5):2127‑2139. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhv042

- Chimpanzees modify recruitment screams as a function of audience composition.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences104(43):17228‑17233. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706741104

- Wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) distinguish between different scream types: evidence from a playback study.Animal Cognition12(3):441‑449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-008-0204-x

- Body size downgrading of mammals over the late Quaternary.Science360(6386):310‑313. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao5987

- Correcting for purifying selection: An improved human mitochondrial molecular clock.The American Journal of Human Genetics84(6):740‑759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.001

- The neuropsychology of dreams: A clinico-anatomical study.ErlbaumURL: http://www.cell.com/trends/cognitive-sciences/pdf/S1364-6613(98)01166-8.pdf

- Becoming human: Evolution and human uniqueness.Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Australia's oldest human remains: age of the Lake Mungo 3 skeleton.Journal of Human Evolution36(6):591‑612. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.1999.0305

- Pan the tool-maker: Investigations into the stone tool-making and tool-using capabilities of a Bonobo (Pan paniscus).Journal of Archaeological Science20(1):81‑91. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1993.1006

- Grooming, gossip, and the evolution of language.Language75(1). https://doi.org/10.2307/417520

- Neural synchrony in brain disorders: Relevance for cognitive dysfunctions and pathophysiology.Neuron52(1):155‑168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.020

- Praxic and nonverbal cognitive deficits in a large family with a genetically transmitted speech and language disorder.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences92(3):930‑933. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.3.930

- Places of art, traces of fire. A contextual approach to anthropomorphic figurines in the Pavlovian. URL: https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/13512

- Mental synthesis involves the synchronization of independent neuronal ensembles.Research Ideas and Outcomes1https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.1.e7642

- Neurobiological mechanisms for nonverbal IQ tests: implications for instruction of nonverbal children with autism.Research Ideas and Outcomes3https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.3.e13239

- Linguistically deprived children: meta-analysis of published research underlines the importance of early syntactic language use for normal brain development.Research Ideas and Outcomes3https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.3.e20696

- Comparison of performance on verbal and nonverbal multiple-cue responding tasks in children with ASD.Autism-Open Access07(05). https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7890.1000218

- Language evolution to revolution: the leap from rich-vocabulary non-recursive communication system to recursive language 70,000 years ago was associated with acquisition of a novel component of imagination, called Prefrontal Synthesis, enabled by a mutation that slowed down the prefrontal cortex maturation simultaneously in two or more children – the Romulus and Remus hypothesis.Research Ideas and Outcomes5https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.5.e38546

- Neuroscience of imagination and implications for human evolution.Journal of Current Neurobiologyhttps://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/skxwc

- Novel linguistic evaluation of prefrontal synthesis (LEPS) test measures prefrontal synthesis acquisition in neurotypical children and predicts high-functioning versus low-functioning class assignment in individuals with autism.Applied Neuropsychology: Child1‑16. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622965.2020.1758700

- Novel prefrontal synthesis intervention improves language in children with autism.Healthcare8(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040566

- On the Origin of the Human Mind.3d.MobileReference[InEnglish]. URL: https://www.amazon.com/Origin-Human-Mind-Andrey-Vyshedskiy/dp/1611988888 [ISBN978-1611988888]

- A system for relational reasoning in human prefrontal cortex.Psychological Science10(2):119‑125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00118

- Syntactic processing depends on dorsal language tracts.Neuron72(2):397‑403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.014

- The growth of language: Universal Grammar, experience, and principles of computation.Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews81:103‑119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.023

- Neuroimaging studies of mental rotation: A meta-analysis and review.Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience20(1):1‑19. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2008.20013

- Features of evolution and expansion of modern humans, inferred from genomewide microsatellite markers.The American Journal of Human Genetics72(5):1171‑1186. https://doi.org/10.1086/375120

- Symbolic use of marine shells and mineral pigments by Iberian Neandertals.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences107(3):1023‑1028. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0914088107