|

Research Ideas and Outcomes :

Research Article

|

|

Corresponding author: Roger Hyam (rhyam@rbge.org.uk)

Received: 22 Apr 2020 | Published: 23 Apr 2020

© 2020 Roger Hyam

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: Hyam R (2020) Greenness, mortality and mental health prescription rates in urban Scotland - a population level, observational study. Research Ideas and Outcomes 6: e53542. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.6.e53542

|

|

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Recent studies have shown an association between vegetation around dwellings and mortality, with mental health as a possible mediator.

OBJECTIVES: Examine whether there is an association between greenness and mortality or greenness and the proportion of the population being prescribed drugs for anxiety, depression or psychosis in urban areas of Scotland.

METHODS: Two greenness maps were prepared based on Landsat 8 Normalised Difference Vegetation Index data from 2013 to 2016, one for summer and one for winter. Greenness was sampled from these maps around each of 91,357 urban postcodes. The greenness data was averaged by 4,883 urban Data Zones covering 71% of the Scottish population and compared with mortality and prescription rate data from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

RESULTS: The areas least green in the summer were found to have higher mortality rates but no association was found between mortality and winter-greenness. The largest relative differences of mortality were around 9%. High levels of summer-greenness were associated with an increase in mental health prescription rates but areas with the highest differences between summer and winter-greenness had lower prescription rates than other areas. The largest relative difference in prescription rate was 17%. All models controlled for overall deprivation. It is hypothesised that the year round greenness of mown grass is associated with increased mental health prescriptions and obscures the benefits of other kinds of vegetation on both mortality and mental health.

DISCUSSION: There is an association between greenness and mortality and greenness and mental health. The association is both statistically significant and large enough to be of importance for policy making. Higher levels of non mown grass vegetation may be preferable for human wellbeing but more detailed understanding of the diversity of plant life in urban areas and how people related to it is required to make more specific recommendations.

Keywords

Mental health, mortality, greenspace, greenness, deprivation, NDVI, beanplot, wellbeing, well-being

Introduction

There is considerable body of work showing the positive effect greenness and green space has on human health in urban areas, recent reviews of evidence include,

Two recent papers from North America have shown a decrease in mortality with increased greenness around subjects’ home addresses, as measured by Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) (

Taking these papers as an inspiration, this ecological study examines whether this effect is visible at the population level in urban areas of Scotland. Three broad research questions are addressed.

- Is there a detectable relationship between mortality rates and greenness near peoples’ homes in urban Scotland?

- Is there a relationship between mental health prescription rate and greenness that may indicate a mediating effect on mortality?

- Are urban areas of multiple deprivation also deprived of greenness?

Methods

The study is primarily concerned with four variables: Greenness (satellite measured NDVI), Deprivation (the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation, SIMD), Mortality (Standardised Mortality Ratio) and the proportion of population being prescribed drugs for anxiety, depression or psychosis. Mental health prescription rate is included because mediation analysis by

Sampling rationale

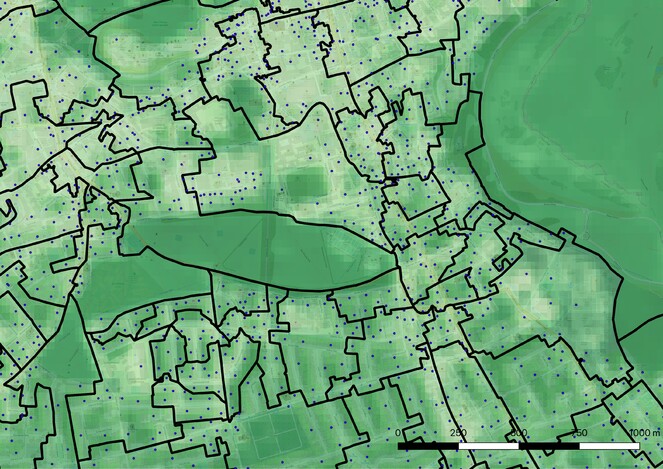

A wide range of population statistics in Scotland are compiled to geographical units called Data Zones (DZ) (Suppl. material

DZs were originally based on primary school catchment areas and then manually adjusted to produce polygons that are a compact shape, take account of physical boundaries, were felt to be homogeneous and have a population of between five hundred and one thousand (

Greenness (NDVI) from Landsat 8

NDVI data was downloaded from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Land Satellites Data System (LSDS) Science Research and Development (LSRD) (

All of Scotland is over 54° North and so for many satellite images the sun is at too low an angle to give reliable surface reflectance data especially in the winter months. Scotland also has an oceanic climate so the ground is often obscured by cloud or mist. To build a detailed, contiguous NDVI map of the whole country therefore requires combining images taken on many satellite passes especially if points are to be sampled multiple times to overcome measurement errors. The images downloaded from USGS were therefore combined. A cloud free version of each NDVI image was created by setting the pixels that corresponded to cloud, snow or water in the Quality Assurance Assessment band to NA. These cloud free images were then combined into a single, mosaic stack of images to cover all of the study area and then averaged down to a single layer as a tiff image. This was done for two seasonal periods, Winter (October, November, December of 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016 combined with January, February, March of 2014, 2015, 2016) and summer (April, May, June, July, August, September of 2014, 2015, and 2016). The resulting two images covering most of Scotland for winters and summers between 2013 and 2016 and formed the basis of subsequent analysis. This data was published separately (

Residential addresses and deprivation

Data on deprivation came from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2016. (

Sampling NDVI

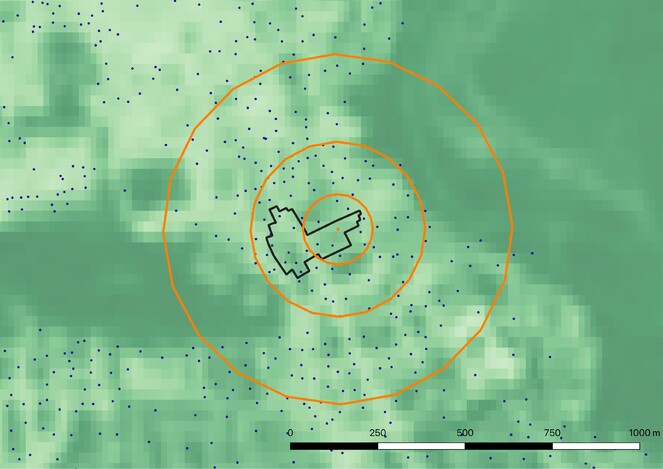

The geospatial point data for each postcode was extracted from the small users postcode dataset. The gBuffer function from the rgeos package in R was used to create circular polygons around each of these points with radii of 100, 250 and 500 m. The NDVI values of the pixels within these buffer zones was averaged for both the summer and winter maps. A further three values were added for each point by calculating the difference between summer and winter at each buffer size as an absolute value. Each postcode then had nine associated values. The mean and standard deviations for each of these values for postcodes within each DZ were calculated resulting in nine measures (and standard deviations) for each DZ that were taken forward into further analysis. DZs were ranked into quintiles of average greenness both for the full set as well as the pure-urban DZs (Suppl. material

Controlling for Deprivation

Throughout the analyses the model was controlled for deprivation using SIMD which is a summary statistic containing both the SMR and the Depression (prescription rate) data as two of its indicators. This biases the results to some degree. The possibility of constructing two new measures of deprivation (SIMD minus Mortality and SIMD minus Depression) was considered. It is apparent from the initial results that the full SIMD has a very small influence on the associations being measured. Any new measures would have even smaller effects, would not change the conclusions being drawn and would be a potential source of error so only the full SIMD, as published, was used here.

Results

The total number of postcode sample points was 91,357. Because of missing data not all of these had NDVI measurements for every pixel. Samples where the buffer had greater than 5% or more missing data were excluded from further analysis. This resulted in 90,689 for the 100 m buffer size, 90,060 for the 250 m buffer size and 89,537 for the 500 m buffer size going forward into the analysis. The average number of sample points per datazone for each combination of season and buffer size was 19.27 (standard dev 10.4).

The DZs used in the study have a total population of 3,776,237, the pure-urban subset represent 1,795,419 people. These are 71% and 34% of the Scottish population of 5.3 million respectively.

There is a constraining relationship between summer-greenness, winter-greenness and seasonal-difference. An urban area that has no vegetation in the summer is unlikely to develop it in the winter to any great extent and an area that is green in the winter is likely to continue being green in the summer. Despite this a minority of DZs showed small negative seasonality. For the 250 m buffer this was 10% both for mixed and pure-urban samples. For mixed-urban the average negative NDVI was 24% of the average positive NDVI, 20% for pure-urban areas. Aerial photos on Google Maps of sites of negative seasonal NDVI change showed a predominance of deciduous trees over lawns from which it was assumed that a major cause of negative NDVI may be less productive tree foliage obscuring highly productive grass during the summer months. This assumption warrants further investigation but for the purposes of this study the absolute value of NDVI difference between summer and winter was used.

The constraints were also evident in the overlap in membership of the NDVI quintiles. For the 250 m buffer the greenest winter quintile shared 62% of its DZs with the greenest summer quintile because areas, typically of mown grass, that were green in the winter were also likely to be amongst the most green areas in the summer. For the least green quintiles 71% of DZs were shared between winter and summer because areas that lacked vegetation were never going to be green either in winter or summer. Of the 449 most seasonal pure-urban DZs only 2% were also in the most winter-green quintile whilst 43% were in the least winter-green quintile.

Following exploratory Pearson’s correlation analyses between all variables an Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was used to model mortality/prescription rate conditional on different levels of greenness whilst controlling for deprivation.

There did not appear to be any meaningful correlations in the exploratory stage of analysis. For summer-greenness r ranged from 0.014 to 0.151 for pure-urban for both mortality and prescription rate. It was lower for mixed-urban. For winter-greenness r ranged from 0.007 to 0.031. Scatter plots of the NDVI against each of the variables didn’t reveal any obvious patterns. The only measure that might be considered weakly correlated was prescription rate against winter-greenness with r ranging from 0.287 to 0.230 for pure-urban areas. This suggests that increased greenness near the home in the winter may be associated with increased (not decreased) use of prescriptions for mental health.

James et al. 2016 specifically reported a 12% lower rate of all-cause non-accidental mortality for subjects living in the highest quintile of greenness compared to those in lowest quintile and so comparisons were made between greenest and least green quintiles for summer and winter as well as the most seasonal and lease seasonal quintiles controlling for mental health prescription rate (SIMD) using the two linear models “Mortality ~ Greenness Quintile + SIMD Rank” and “Depression ~ Greenness Quintile + SIMD Rank” in the R function lm. For the pure-urban datasets this gave significant differences between the extreme quintiles for all combinations of greenness measure and buffer size apart from mortality versus seasonality (See Tables

Comparison of Standardised Mortality Rates (SMR) in greenest and least green quintiles for pure-urban Data Zones controlling for Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). (n=2,246). Deltas are absolute changes in SMR and SIMD.

|

Buffer Size |

Mortality (SMR) |

Deprivation (SIMD) |

|||||

|

Δ |

t |

p |

Δ |

t |

p |

||

|

Summer |

100 |

-10.238 |

-2.922 |

0.004 |

-0.014 |

-18.542 |

<0.001 |

|

250 |

-9.410 |

-2.761 |

0.006 |

-0.014 |

-18.504 |

<0.001 |

|

|

500 |

-10.136 |

-3.476 |

0.001 |

-0.014 |

-21.393 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Winter |

100 |

-8.926 |

-3.041 |

0.002 |

-0.014 |

-22.072 |

<0.001 |

|

250 |

-7.260 |

-2.489 |

0.013 |

-0.014 |

-21.679 |

<0.001 |

|

|

500 |

-8.609 |

-2.890 |

0.004 |

-0.013 |

-20.229 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Seasons |

100 |

-2.384 |

-0.899 |

0.369 |

-0.013 |

-21.955 |

<0.001 |

|

250 |

-5.610 |

-1.869 |

0.062 |

-0.013 |

-19.960 |

<0.001 |

|

|

500 |

-5.610 |

-1.869 |

0.062 |

-0.013 |

-19.960 |

<0.001 |

|

Comparison of prescription rates for mental health with greenest and least green quintiles for pure-urban Data Zones (DZ) controlling for Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). (n=2,246). Deltas are absolute percentage change in prescription rate and SIMD.

|

Buffer Size |

Depression |

Deprivation (SIMD) |

|||||

|

Δ |

t |

p |

Δ |

t |

p |

||

|

Summer |

100 |

2.70% |

12.922 |

<0.001 |

-2.16E-05 |

-47.193 |

<0.001 |

|

250 |

2.58% |

12.587 |

<0.001 |

-2.18E-05 |

-47.731 |

<0.001 |

|

|

500 |

2.55% |

12.140 |

<0.001 |

-2.13E-05 |

-45.866 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Winter |

100 |

3.02% |

15.122 |

<0.001 |

-1.98E-05 |

-45.681 |

<0.001 |

|

250 |

3.06% |

15.824 |

<0.001 |

-1.97E-05 |

-46.997 |

<0.001 |

|

|

500 |

3.02% |

15.319 |

<0.001 |

-1.97E-05 |

-45.380 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Seasons |

100 |

-1.43% |

-6.991 |

<0.001 |

-1.96E-05 |

-44.214 |

<0.001 |

|

250 |

-1.24% |

-5.799 |

<0.001 |

-1.90E-05 |

-41.429 |

<0.001 |

|

|

500 |

-1.24% |

-5.799 |

<0.001 |

-1.90E-05 |

-41.429 |

<0.001 |

|

The mortality rate (SMR) is centred on a value of 100 so unsurprisingly the mean for all DZs in the SIMD dataset is 99.766 (sd=44.866). The mean for DZs in this study was 104.301 (sd=49.060) and 107.853 (sd=54.336) for the pure-urban areas showing an underlying increase in mortality rates in more urbanised areas but with a great deal of variability. The largest differences shown in Table

The mean prescription rate for all DZs in the SIMD data is 17.55% (sd=5.01). The mean for all DZs in this study was 18.07% (sd=5.26) for mixed-urban and 17.67% (sd=5.66) for pure-urban areas. The largest differences shown in Table

Finding significant differences between the highest and lowest quintiles but not an overall linear relationship suggested a more complex pattern. In an ANCOVA for quintiles of all combinations of greenness measure against mortality and prescription rate for both mixed-urban and pure-urban sets controlling for SIMD there were significant differences (p < 0.01) in all combinations apart from two cases. No significant difference between quintiles was found for any buffer sizes in winter-greenness verses mortality in the pure-urban subset of DZs and in seasons verses mortality for the 100 m buffer size in the mixed-urban set.

To understand the size of the statistically significant differences found Cohen’s d was calculated for the differences between highest and lowest quintiles for 250 m buffers for pure-urban DZ. Summer-greenness was associated with a small to medium changes in both mortality and prescription rate (Cohen’s d 0.265 and 0.296). Seasonal-difference was associated with medium size differences in mortality (Cohen’s d 0.467). Winter-greenness and seasonal-difference were associated with medium to large differences in prescription rates, albeit in opposite directions (Cohen’s d 0.728 and 0.764).

To help interpret these relationships Tukey’s HSD test was carried out for each combination of variables for the five quintiles G1 (least green or least seasonal) to G5 (greenest or most seasonal). Significance in these comparisons is taken as p < 0.01.

Mortality and summer-greenness

For pure-urban DZs at 250 m G1 was significantly higher than all other quintiles (p < 0.01) with the difference ranging from 11.550 to 15.231 SMR. G2 through G5 didn’t vary from each other significantly at all. This pattern was stronger at 100 m buffer size but broke down at 500 m buffer size. For the mixed-urban DZs the pattern was similar but didn’t break down at the 500 m buffer size.

Mortality and winter-greenness

As per the ANCOVA for pure-urban DZs there were no significant differences between quintiles at any buffer size. For the mixed-urban DZs G5 was significantly lower than other quintiles at 500 m but this broke down at 100 m and 250 m with low levels of significance of any differences between quintiles compared.

Mortality and seasonal difference

For pure-urban DZs G5 was significantly lower than all the other quintiles for 250 m which held for 100 m and 500 m. For mixed-urban DZs G1 and G5 had significant lower mortality rates at larger buffer sizes only but the confidence levels were low and the difference disappeared for the 100 m buffer size.

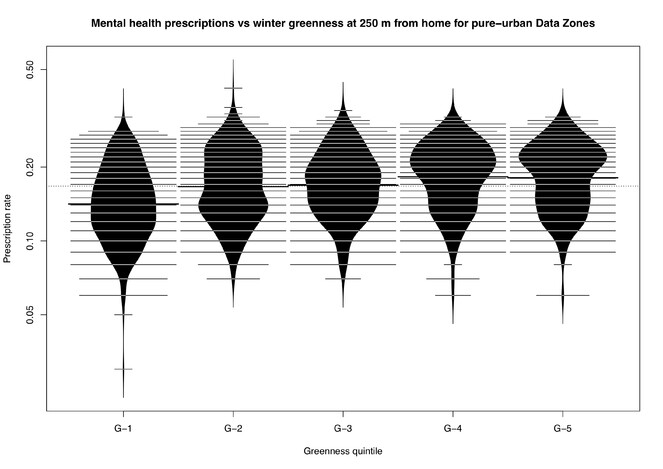

Mental health prescription rate and summer-greenness

For pure-urban DZs there were significant differences between most of the quintiles with the largest being between G1 and the rest. Notably higher levels of greenness were associated with higher prescription rates. For mixed-urban this did not hold. There were significant differences between some combinations of quintiles but confidence levels were low apart from at 500 m where G5 stood out as having small but significant reduced prescription rates compared to the other quintiles.

Mental health prescription rate and winter-greenness

For pure-urban DZs there were significant differences between most of the quintiles which were maintained at all buffer sizes. Areas of higher winter-greenness had higher prescription rates. These differences are visualised in Fig.

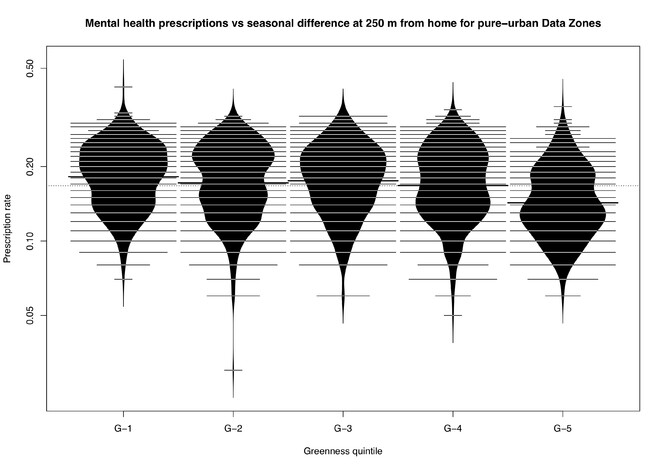

Mental health prescription rate and seasonal difference

The significant differences between quintiles approximated a mirror image of that for pure-urban DZs, winter-greenness for 250 m and 500 m buffers. These differences are visualised in Fig.

Discussion

Mechanisms for how the benefits of greenness and greenspace on health may occur fall into three broad areas: Physiological mechanisms involve vegetation ameliorating the hostile aspects of the built environment (

Urban areas in Scotland fall within a single, oceanic climatic zone at or close to sea level. Although there are many deciduous trees in some areas there is also a large amount of mown grass which grows nearly year around. One would therefore expect a lower level of variance in NDVI than in the North American studies which cover a range of climatic zones and altitudes. The published figures suggest this may be the case. The mean NDVI for 250 m buffer zone of the current study is 0.48 (sd=0.08) while

The association of mortality rates with greenness needs to be interpreted in the context of the constrained pattern of seasonal differences, that areas green in winter are also green in summer but areas not green in summer are never green in winter. No overall relationship between winter-greenness and mortality was found, only a relationship between summer- greenness and mortality, yet a large amount of that summer-greenness must be the result of the same vegetation that causes winter-greenness. This is confirmed by the seasonal-difference data where differences in mortality are again found suggesting that the relationship is only with summer-greenness. Only the least summer-green areas have a detectable rise in mortality rate suggesting that there is an absolute level of summer-greenness beyond which no benefit to mortality rates occurs. The influence of greenness on mortality has to approach an asymptote at some level and, because of the low variance in Scottish urban greenness, it is plausible the majority of the urban areas are at or above this level. Any planning policy might therefore only look at increasing summer-greenness in a restricted range of areas. Alternatively differences in mortality at higher levels of summer-greenness may be obscured by associated winter-greenness and if this could be controlled for the relationship may be more linear. This is supported by the most seasonal areas having a fall in mortality rate compared to the rest.

The findings on mental health prescription rate were initially surprising. It was expected that, as a potential mediator of mortality rate, they would be found to vary either in the same direction as the mortality rate or not at all. The observed relationship could be entirely spurious but the size of the differences and level of statistical support as well as the robustness between pure-urban and mixed-urban datasets make this unlikely. There could be a direct causal link between winter-greenness and prescription rates but it seems unlikely that mown lawns cause mental health problems or attract people with poor mental health. A more likely explanation is a confounding variable that leads to the geospatial association of a this kind of vegetation and mental illness. Deprivation would be the lead candidate but an attempt was made to controlled for this in the analysis. Identification of the confounder will require other studies but the restricted range of climatic characteristics of urban Scotland rule out some of the physiological candidates such as heat stress. Pollution may be a candidate in association with busy roads but psychosocial mechanisms may also play a part (

Despite varying in the opposite direction to mortality, mental health prescription rate might still be a mediator of mortality rate or share a confounding variable. Prescription rates fall with increased seasonal difference just as mortality rates do. More deciduous areas have lower mortality rates and reduced prescription rates suggesting, again, that the nature of the vegetation is as important as the amount. A recent study from the Netherlands (

This more complex relationship between greenness and health has implications for the suggested mechanisms as to how nature effects well-being. Publicly accessible, mown parkland might appear to increase the overall greenness in a community but have little effect on noise and air pollution or provide meaningful social spaces that are visited throughout the year. In contrast street trees and a patchwork of private or shared gardens may be more beneficial, provided they are tended in a way that maintains sufficient volume of seasonally diverse vegetation. Looking at new mothers

Conclusions

There is a relationship between greenness around peoples’ homes and standardised mortality rates at the DZ level (Research question 1). Least green areas have higher mortality rates. This relationship only holds for levels of greenness in summer, not winter. It only exists for the least green 20% of areas, the other 80% being indistinguishable. Areas with highest levels of seasonal difference have lower mortality rates compared to others suggesting that the kind of vegetation plays a role. The sizes of differences in mortality are small to medium representing a relative difference of around 9%.

Higher levels of greenness around homes is associated with higher mental health prescription rates especially greenness in the winter (Research question 2). There is a stronger relationship closer to the home. The opposite is true of seasonal difference. Higher seasonal difference is associated with lower prescription rates. The differences are medium to large in size with the largest seasonal difference having a relative difference in prescription rate of 17%.

Because relationships between greenness and mortality and mental health prescription rates hold despite controlling for deprivation it is unlikely areas of higher deprivation are also deprived of raw greenness in general (Research question 2). This does not exclude the kind of vegetation playing a role in deprivation or lack of greenness playing a role under certain circumstances.

This is an ecological, observational study and no causation can be concluded from the fact that variables measured vary together however the context, level of support and size of the variation suggests that the variables may form parts of chains of causation rather than their association merely being chance. Further investigation of these relationships requires patient level data on the one hand and more granular information about kinds of vegetation and people’s lived experience of that vegetation on the other. Our urban environments are complex cultural constructs which require a truly interdisciplinary approach to understand.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant in aid from the Scottish Government. It would not have been possible if the Scottish government, NASA and USDA hadn’t made their data openly available. Dr Antje Ahrends gave valuable advice on statistical analysis.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares he has no actual or potential competing financial interests.

References

-

The importance of green spaces to public health: a multi-continental analysis.Ecological Applications28(6):1473‑1480. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1748

-

Attention restoration theory: Exploring the role of soft fascination and mental bandwidth.Environment and Behavior51:1055‑1081. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916518774400

-

Urban woodlands: their role in reducing the effects of particulate pollution.Environmental Pollution99(3):347‑360. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0269-7491(98)00016-5

-

The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: A literature review on restorativeness.Behavioral Sciences4(4):394‑409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4040394

-

Urban greenness and mortality in Canada's largest cities: a national cohort study.The Lancet Planetary Health1(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(17)30118-3

-

Surrounding Greenness and exposure to air pollution during pregnancy: An analysis of personal monitoring data.Environmental Health Perspectives120(9):1286‑1290. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104609

-

The relationship between trees and human health.American Journal of Preventive Medicine44(2):139‑145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.066

-

Is tree loss associated with cardiovascular-disease risk in the Women's Health Initiative? A natural experiment.Health & Place36:1‑7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.08.007

-

The relationship between the natural environment and individual-level academic performance in Portland, Oregon.Environment and Behavior52(2):164‑186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916518796885

-

Residential greenspace might modify the effect of road traffic noise exposure on general mental health in students.Urban Forestry & Urban Greening34:233‑239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.06.022

-

Residential green space quantity and quality and symptoms of psychological distress: a 15-year longitudinal study of 3897 women in postpartum.BMC Psychiatry18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1926-1

-

A review of epidemiologic studies on greenness and health: Updated literature through 2017.Current Environmental Health Reports5(1):77‑87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-018-0179-y

-

Residential green spaces and mortality: A systematic review.Environment International86:60‑67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.013

-

Research note: Natural environments and prescribing in England.Landscape and Urban Planning151:103‑108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.02.002

-

Nature and health.Annual Review of Public Health35(1):207‑228. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443

-

More green space is related to less antidepressant prescription rates in the Netherlands: A Bayesian geoadditive quantile regression approach.Environmental Research166:290‑297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.010

-

NDVI raster maps of Scotland for 2013-2016 used to analyse correlations between greenness, mortality and mental health.1.Zenodo. Release date:2020-3-25. URL: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3727288

-

Exposure to greenness and mortality in a nationwide prospective cohort study of women.Environmental Health Perspectives124(9):1344‑1352. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1510363

-

Beanplot: A boxplot alternative for visual comparison of distributions.Journal of Statistical Software28https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v028.c01

-

The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework.Journal of Environmental Psychology15(3):169‑182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

-

Effects of flowering, foliation, and autumn colors on preference and restorative potential for designed digital landscape models.Environment and Behaviorhttps://doi.org/10.1177/0013916518811424

-

Beyond the school grounds: Links between density of tree cover in school surroundings and high school academic performance.Urban Forestry & Urban Greening38:42‑53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.11.001

-

Morbidity is related to a green living environment.Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health63(12):967‑973. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.079038

-

Do urban environments increase the risk of anxiety, depression and psychosis? An epidemiological study.Journal of Affective Disorders150(3):1019‑1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.032

- https://landsat.gsfc.nasa.gov/the-worldwide-reference-system/. Accessed on: 2018-6-27.

-

National Records of Scotland Postcodes 2017-2. https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/geography/our-products/scottish-postcode-directory/2017-2. Accessed on: 2018-6-27.

-

Air pollution removal by urban trees and shrubs in the United States.Urban Forestry & Urban Greening4:115‑123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2006.01.007

-

Scottish neighbourhood statistics data zones background information.Scottish Executive,45pp.

-

Is all urban green space the same? A comparison of the health benefits of trees and grass in New York City.International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health14(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111411

-

Green spaces and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies.The Lancet Planetary Health3(11). https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(19)30215-3

-

Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation. https://simd.scot/#/simd2020/BTTTFTT/9/-4.0000/55.9000/. Accessed on: 2018-6-27.

-

Tree cover and species composition effects on academic performance of primary school students.PLOS One13(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193254

-

Research note: Urban street tree density and antidepressant prescription rates—A cross-sectional study in London, UK.Landscape and Urban Planning136:174‑179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.12.005

-

Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment.Behavior and the Natural Environment85‑125. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3539-9_4

-

Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments.Journal of Environmental Psychology11(3):201‑230. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-4944(05)80184-7

- https://espa.cr.usgs.gov/. Accessed on: 2018-6-27.

-

Mitigating stress and supporting health in deprived urban communities: The importance of green space and the social environment.International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health13(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13040440

-

Urban green spaces and health: A review of evidence.WHO Regional Office for Europe,Copenhagen. [InEnglish]. URL: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/321971/Urban-green-spaces-and-health-review-evidence.pdf?ua=1

-

An ecological study of the association between area-level green space and adult mortality in Hong Kong.Climate5(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/cli5030055

-

A conceptual framework for studying urban green spaces effects on health.Journal of Urban Ecology3(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/jue/jux015

Supplementary materials

A vector map layer of the boundaries of the Data Zones used in the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

List of products downloaded from USGS and used to create summer and winter maps.

List of small user postcodes as downloaded from Scotland Registry.

Nine data tables containing the NDVI and SIMD data used in the analysis.