|

Research Ideas and Outcomes :

Policy Brief

|

|

Corresponding author: Thomas Borsch (t.borsch@bgbm.org)

Received: 31 Jan 2020 | Published: 03 Feb 2020

© 2020 Thomas Borsch, Albert-Dieter Stevens, Eva Häffner, Anton Güntsch, Walter G. Berendsohn, Marc Appelhans, Christina Barilaro, Bánk Beszteri, Frank Blattner, Oliver Bossdorf, Helmut Dalitz, Stefan Dressler, Rhinaixa Duque-Thüs, Hans-Joachim Esser, Andreas Franzke, Dethardt Goetze, Michaela Grein, Uta Grünert, Frank Hellwig, Jörn Hentschel, Elvira Hörandl, Thomas Janßen, Norbert Jürgens, Gudrun Kadereit, Timm Karisch, Marcus Koch, Frank Müller, Jochen Müller, Dietrich Ober, Stefan Porembski, Peter Poschlod, Christian Printzen, Martin Röser, Peter Sack, Philipp Schlüter, Marco Schmidt, Martin Schnittler, Markus Scholler, Matthias Schultz, Elke Seeber, Josef Simmel, Michael Stiller, Mike Thiv, Holger Thüs, Natalia Tkach, Dagmar Triebel, Ursula Warnke, Tanja Weibulat, Karsten Wesche, Andrey Yurkov, Georg Zizka

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: Borsch T, Stevens A-D, Häffner E, Güntsch A, Berendsohn WG, Appelhans MS, Barilaro C, Beszteri B, Blattner FR, Bossdorf O, Dalitz H, Dressler S, Duque-Thüs R, Esser H-J, Franzke A, Goetze D, Grein M, Grünert U, Hellwig F, Hentschel J, Hörandl E, Janßen T, Jürgens N, Kadereit G, Karisch T, Koch MA, Müller F, Müller J, Ober D, Porembski S, Poschlod P, Printzen C, Röser M, Sack P, Schlüter P, Schmidt M, Schnittler M, Scholler M, Schultz M, Seeber E, Simmel J, Stiller M, Thiv M, Thüs H, Tkach N, Triebel D, Warnke U, Weibulat T, Wesche K, Yurkov A, Zizka G (2020) A complete digitization of German herbaria is possible, sensible and should be started now. Research Ideas and Outcomes 6: e50675. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.6.e50675

|

|

Abstract

Plants, fungi and algae are important components of global biodiversity and are fundamental to all ecosystems. They are the basis for human well-being, providing food, materials and medicines. Specimens of all three groups of organisms are accommodated in herbaria, where they are commonly referred to as botanical specimens.

The large number of specimens in herbaria provides an ample, permanent and continuously improving knowledge base on these organisms and an indispensable source for the analysis of the distribution of species in space and time critical for current and future research relating to global biodiversity. In order to make full use of this resource, a research infrastructure has to be built that grants comprehensive and free access to the information in herbaria and botanical collections in general. This can be achieved through digitization of the botanical objects and associated data.

The botanical research community can count on a long-standing tradition of collaboration among institutions and individuals. It agreed on data standards and standard services even before the advent of computerization and information networking, an example being the Index Herbariorum as a global registry of herbaria helping towards the unique identification of specimens cited in the literature.

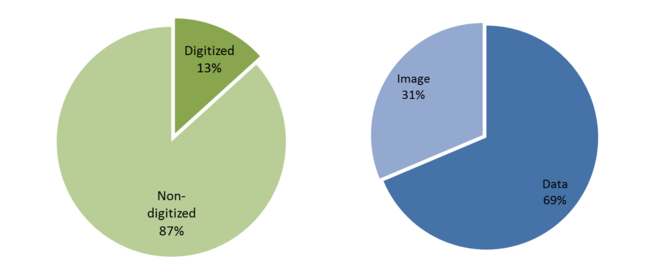

In the spirit of this collaborative history, 51 representatives from 30 institutions advocate to start the digitization of botanical collections with the overall wall-to-wall digitization of the flat objects stored in German herbaria. Germany has 70 herbaria holding almost 23 million specimens according to a national survey carried out in 2019. 87% of these specimens are not yet digitized. Experiences from other countries like France, the Netherlands, Finland, the US and Australia show that herbaria can be comprehensively and cost-efficiently digitized in a relatively short time due to established workflows and protocols for the high-throughput digitization of flat objects.

Most of the herbaria are part of a university (34), fewer belong to municipal museums (10) or state museums (8), six herbaria belong to institutions also supported by federal funds such as Leibniz institutes, and four belong to non-governmental organizations. A common data infrastructure must therefore integrate different kinds of institutions.

Making full use of the data gained by digitization requires the set-up of a digital infrastructure for storage, archiving, content indexing and networking as well as standardized access for the scientific use of digital objects. A standards-based portfolio of technical components has already been developed and successfully tested by the Biodiversity Informatics Community over the last two decades, comprising among others access protocols, collection databases, portals, tools for semantic enrichment and annotation, international networking, storage and archiving in accordance with international standards. This was achieved through the funding by national and international programs and initiatives, which also paved the road for the German contribution to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF).

Herbaria constitute a large part of the German botanical collections that also comprise living collections in botanical gardens and seed banks, DNA- and tissue samples, specimens preserved in fluids or on microscope slides and more. Once the herbaria are digitized, these resources can be integrated, adding to the value of the overall research infrastructure. The community has agreed on tasks that are shared between the herbaria, as the German GBIF model already successfully demonstrates.

We have compiled nine scientific use cases of immediate societal relevance for an integrated infrastructure of botanical collections. They address accelerated biodiversity discovery and research, biomonitoring and conservation planning, biodiversity modelling, the generation of trait information, automated image recognition by artificial intelligence, automated pathogen detection, contextualization by interlinking objects, enabling provenance research, as well as education, outreach and citizen science.

We propose to start this initiative now in order to valorize German botanical collections as a vital part of a worldwide biodiversity data pool.

Keywords

Herbaria, Digitization, Botanical Collections, Research Infrastructure, Biodiversity Data, Conservation, Biomonitoring, Taxonomy, Semantics, Artificial Intelligence

Introduction

Plants, fungi and algae are important components of global biodiversity, and they are the basis of all ecosystems. Specimens of all three groups of organisms are accommodated in herbaria where they are commonly referred to as botanical specimens. As primary producers of biomass, plants and algae are fundamental for ecosystem services including carbon sequestration and the provision of oxygen. Primary producers also fuel marine and terrestrial food webs supporting the existence of a huge diversity of living organisms. Fungi are the major decomposers of organic material and are obligate symbionts of land plants (mycorrhiza) and many algae (lichen symbiosis). Plants, fungi and algae are the basis for human well-being, providing food, materials and medicines. To protect and sustainably use this wealth of different organisms on our planet in line with global goals such as the sustainable development goals (United Nations 2015)*

Information on plants, algae and fungi present in an area, as well as on global distribution patterns of species and their changes over time is of primary importance. Herbaria play a pivotal role in this respect because each collected and preserved specimen represents a verifiable record of the presence of a species in a defined place at a specific time. The large numbers of specimens in herbaria provide an ample geographic coverage and information on character variability (both morphological and molecular), and this information is continuously improving with the increasing number of specimens. Most importantly, the taxonomic identification of these specimens can be verified at any time, offering a robust knowledge base in which new research findings from the ongoing investigation of life with current methods can be continuously integrated. In this context it is important to consider that scientific approaches of elucidating the ancestral relationships of organisms and delimiting species and taxonomic groups - the field of biological systematics - has been revolutionized by the advent of (mainly molecular) phylogenetics as an evolutionary method and by electronic tools that will enable an integrative taxonomy. In addition to past and present distribution records of species, herbaria provide material samples for biological research in diverse fields (

The botanical research community can count on a long-standing tradition of collaboration among institutions and individuals. Herbaria are essentially forming a global infrastructure for research, with individual specialists for specific organismic groups contributing their expertise to many collaborative projects. This is fostered by the tradition of collecting and distributing duplicate specimens, and sharing of expert identifications. The botanical community came together to agree on data standards and standard services even before the advent of computerisation and information networking. For example, the Index Herbariorum*

Collaborative efforts for creating floras, i.e. inventories of plants from a defined region with detailed descriptions and identification keys, also go back a long way. A well-known example is the Flora Brasiliensis (

Collaboration has also been fundamental to the development of digitization in the botanical community, possibly best demonstrated by the Global Plants Initiative (GPI)*

Botanical Collections in Germany

Botanical collections are composed of a variety of different kinds of specimens including dried specimens mounted on herbarium sheets (higher plants and ferns) or in envelopes (bryophytes, fungi, algae), living collections of botanical gardens and seed banks, DNA and tissue collections, specimens preserved in fluids, wood, fruit, seed, fibre, and pollen collections, as well as micro-preparations on microscope slides. Worldwide as many as 388 million specimens are stored in nearly 3,100 herbaria in 178 countries. The three countries in Europe with the highest number of herbarium specimens are France, the UK, and Germany with 25.96, 22.31, and 22.16 million specimens, respectively (

In Europe 37 countries have listed herbaria in the Index Herbariorum. The 15 countries with the highest number of specimens and the total numbers are given here (extracted from

|

Country |

Number of Herbaria |

Number of specimens in million |

Percent of specimens in European herbaria |

Percent of specimens in herbaria worldwide |

|

France |

76 |

25.9 |

14.8 |

6.7 |

|

U.K. |

107 |

22.3 |

12.7 |

5.7 |

|

Germany |

70 |

22.2 |

12.6 |

5.7 |

|

Switzerland |

17 |

12.0 |

6.8 |

3.1 |

|

Sweden |

10 |

11.9 |

6.8 |

3.1 |

|

Italy |

78 |

11.6 |

6.6 |

3.0 |

|

Austria |

19 |

10.5 |

6.0 |

2.7 |

|

Czech Republic |

45 |

8.4 |

4.8 |

2.2 |

|

Netherlands |

15 |

7.4 |

4.2 |

1.9 |

|

Spain |

56 |

6.2 |

3.5 |

1.6 |

|

Finland |

11 |

5.5 |

3.1 |

1.4 |

|

Poland |

32 |

5.3 |

3.0 |

1.4 |

|

Belgium |

10 |

5.1 |

2.9 |

1.3 |

|

Denmark |

2 |

3.6 |

2.0 |

0.9 |

|

Norway |

7 |

3.4 |

1.9 |

0.9 |

|

EUROPE total |

688 |

176 Mio |

100 |

45 |

In order to foster the digitization efforts in botanical collections two workshops with participants representing many of the botanical collections in Germany were held at Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum (BGBM) in Berlin in February 2017 and in February 2019. During these workshops a survey on key data on the collections in Germany was organized. Data collated and discussed included the number and kind of mounted and unmounted specimens, the available percentage and degree of digitization (e.g. ranging from label information as text in a data base to high resolution images), the state of curation (e.g. availability of staff dedicated to curation and technical management of the collection), the institutional setup of the collection (i.e. supported by a university and state funded; with partial or complete federal support, mostly in a Leibniz institute; state or municipality funded museum; or private registered association), the availability of infrastructure for digitization and data management, and the annual growth of the collections. The most recent survey among the herbaria of Germany was performed in 2019 and covered collections in 62 herbaria.

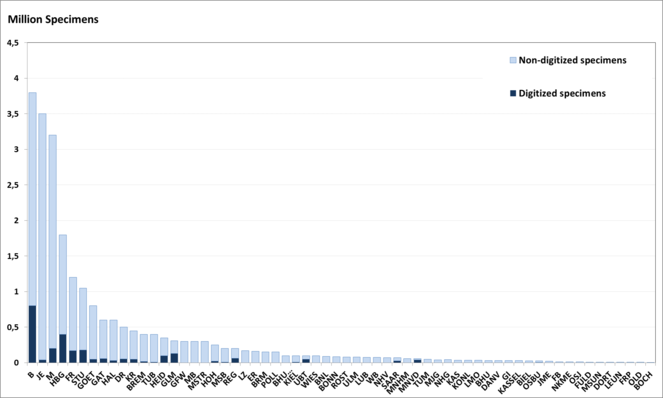

According to this survey, the number of specimens in these 62 herbaria exceeded the number listed in Index Herbariorum for all 70 herbaria in Germany. Our survey revealed an estimated number of 22.8 million specimens that are held by these 62 institutions, of which 19.8 million specimens or 87% are not yet digitized (Fig.

Of the 22.8 million specimens held in the herbaria 53% are objects mounted on cardboard sheet (mostly seed plants, ferns, lycophytes, macroalgae), which lend themselves to imaging of the entire specimen. Another 21% are not mounted yet and 26% are stored in other forms, such as in boxes, in envelopes, on slides, or in liquids (mostly bryophytes, lichens, fungi, and algae). For these special formats photographic capture of label data is of interest, which has to be done in a separate work flow. Imaging often requires the consideration of specific objectives and may require specific expertise on the taxonomic group and special preparation to visualize characters relevant for identification. For example in the large herbarium Munich (M) 75% of the flat objects are vascular plants, and 25% are bryophytes, macroalgae, and phytopathogenic fungi. In the largest German herbarium in Berlin (B) 71% of the specimens are flat objects (seed plants and ferns), 28,5% are stored in envelopes and boxes (bryophytes, licophytes, fungi), and only 0,5% are on slides or in liquids (algae). It is reasonable to expect a similar distribution in most of the other German herbaria.

The rich academic history of German universities and the federal structure of the country today results in more distributed contributions compared to the more centralised collections within countries of similar size and history of science. The ten largest of the 62 herbaria harbour approximately 75% of the total number of specimens, whereas the majority of herbaria hold between 50 and 100 thousand specimens (Fig.

Most of the herbaria are part of a university (34 herbaria with a total of 14.3 million specimens). Fewer belong to municipal museums (10) or state museums (8), with a total of six million specimens. Six herbaria with a total of 2.5 million specimens belong to institutions also supported by federal funds such as Leibniz institutes, and four belong to non-governmental organisations with a total of 0.06 million specimens. A common data infrastructure must therefore integrate different kinds of institutions.

Digitization of Herbaria in Germany

Digitization within 23 herbaria in Germany has so far resulted in three million digitized specimens. These herbaria hold 19.5 million specimens, approximately 86% of the total holdings in the 62 herbaria surveyed in Germany. In most cases, only textual data (label information) have been recorded (70%). More rarely (30%), entire specimens have been photographed or scanned in addition to textual data. An average of 48,000 specimens are digitized per year; 75% are sheet-mounted specimens. Given the figure above of 200,000 accessions per year, this implies that currently only about a quarter of newly acquired specimens are being digitized (with huge differences between institutions). Only three to four service stations strategically placed in larger herbaria throughout Germany would be sufficient to digitize this annual increase in specimens in a cost-efficient way.

Most of the type specimens digitized are resulting from the aforementioned Global Plants Initiative (GPI). German collections contributed 224,324 type specimens and specimens from important historical collections to GPI. With a resolution of 600 dpi and implemented quality control for the images, as well as (mostly) detailed metadata, the GPI data are forming a high-quality resource which is made available through a common data portal. However, curation of the records is left to the individual contributors and there is no centralised quality control, especially with respect to taxonomic identification and actual type status, after the end of the project phase. Infrastructures such as the one proposed here could help to remedy that situation. Also, the establishment of globally unique identifiers for physical specimens (

Because of the specific distribution and setup of the botanical collections in Germany, an integrative concept for their comprehensive digitization was already envisaged in the architecture of a proposal to transform Germany’s natural history collections into an integrated research infrastructure within the DCOLL project (DCOLL - German Natural Sciences Collections as an Integrated Research Infrastructure*

Despite the successful industrial-scale digitization initiatives in other countries, the use of high throughput digitization techniques like a conveyor belt or digitization station have - for financial reasons - only been an exception up to now in Germany. However, 33 herbaria (53.2%) do possess basic equipment like scanners, digital cameras, and microscopes and use them to digitize their specimens. At BGBM, a project is testing a mass throughput digitization station designed for museum objects (Fig.

Overall digitization of specimens that are not sheet-mounted still requires the development of efficient techniques and in some cases (e. g. microscopic slides) considerable curatorial effort. This is, however, especially relevant for specific herbaria that hold larger numbers of unmounted specimens. Digitizing the label information of boxes and envelopes containing bryophytes, lichens, and fungi mounted on flat card board could make use of the mass throughput workflow tested at BGBM. Other specimens would currently substantially increase the effort and time period needed and should thus rather be digitized in the longer term and driven by demand. Here, we do advocate starting the digitization of German botanical collections with the complete digitization of the flat objects stored in herbaria.

Experiences and Achievements in other Countries

The successful digitization initiatives in Naturalis (Netherlands), Digitarium (Finland), and the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (France) show that major herbaria can be digitized in just a few years. The Paris Herbarium was fully digitized between 2012 and 2019 and now delivers 5,400,000 digital records to GBIF for free use by the international research community (

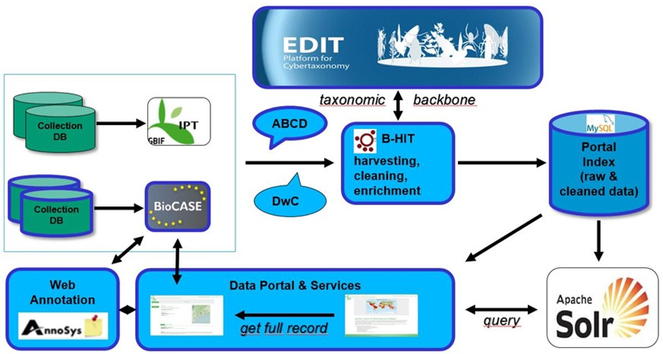

Technical Components for Infrastructures of Scientific Collections

An overall digitization of the German herbaria requires the setup of an efficient digital infrastructure for storage, archiving, content indexing, networking as well as standardized access for the scientific use of digital objects. The digital storage and linking of botanical collection objects can be based on a standards-based portfolio of technical components already developed and tested by the Biodiversity Informatics Community over the last two decades. Therefore, the focus can be on upscaling with an extensive use of well-established components, as well as digitization protocols established at individual institutions (e.g.

Standards and access protocols

A digital infrastructure for the German botanical collections must be based on common data standards and access protocols with which distributed data can be uniformly queried and evaluated. Access to Biological Collection Data (ABCD,

A number of protocols and software components have been developed and successfully implemented for access to distributed databases. These include Distributed Generic Information Retrieval (DiGIR*

Data capture and collection databases

The overall digitization of German herbaria requires the decentralized availability of systems with which collection data can be collected, curated and connected to national and international networks. In the field of botany, various powerful software systems (e. g. Virtual Herbaria JACQ, Diversity Workbench, Symbiota, Brahms, Botalista, SeSam, 4D) are already successfully used. In recent years there has been a trend towards cooperation in system development and joint data management.

In Germany, for example, the collection management systems JACQ and Diversity Workbench are cooperative developments used by a steadily growing number of herbaria.

The JACQ system is presently used by nine institutions and covers 40% of all digitized records in German herbarium collections. JACQ is used worldwide by 41 institutions in 14 countries*

The Diversity Workbench is presently used by ten herbaria in Germany and covers a large number of vascular plants records as well as the majority of all digitized records in German fungal and bryophyte collections (700,000 records altogether). Diversity Workbench is used by more than 30 institutions, mainly in Germany*

The curation of botanical collection data in cooperative online networks has a number of advantages that are of great value for the overall digitization of German herbaria. For example, as the amount of data already entered into the systems grows, the likelihood that metadata for new objects have already been entered for the associated duplicates and exsiccatal series in other collections increases. The research- and society-relevant (meta-)data can then be jointly curated in agreed interfaces and be re-used. In addition, agreements on data entry conventions and data standards can be easily implemented in interfaces accessing various underlying database systems. Automatic and semi-automatic data quality control and semantic annotation workflows can be uniformly applied to relevant data from multiple sources. And finally, technical interfaces to national and international data networks could be developed and maintained cooperatively, which means considerable savings in costs. In comparison to other kinds of natural history collections, herbaria are particularly suitable as a pilot project for jointly operated online editing interfaces, e.g. in the context of DiSSCo, the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) and the National Research Data Infrastructure (NFDI), due to their existing high standardization and cooperative community. Such environments for a common management of research- and society-relevant collection data will be a valuable add-on to the established in-house collection management systems with a lot of institution-specific and process-oriented functions and a high data security level.

Indexing and portals

In a predominantly decentralized data infrastructure for digital herbaria, central components must be set up that guarantee fast access to the entire data stock and provide functions that can be most effectively implemented centrally. Over the last few years, a number of portal systems have been developed for this function and are available as open source software. These include, for example, the Atlas of living Australia (ALA)*

These portal systems are quality checked, cleaned, and stored in an index database for quick access. Data providers receive logs of the identified quality problems and can clean them up at source. The possibility of extending user queries to taxonomic synonyms is provided by connecting taxonomic backbone databases. The unified processing of the primary data enabled the development of standardized portals which, based on the central index, provide data access via web pages and web services. The different portals of the Global Genome Biodiversity Network*

Semantics and annotation

The semantic enrichment of data with links to external resources (persons, geographic features, habitat types, exsiccatal series etc.) plays an increasingly important role in the integration of collection data across institutions. The enriched data is delivered via Linked Open Data (LOD) compatible identifiers (

The bibliographic account of exsiccatal series "IndExs"*

AnnoSys (

European botanical collections have created a common freely available "benchmark dataset" to evaluate and compare innovative methods of content indexing and semantic annotation (

International networking

By using existing international standards of biodiversity informatics as well as established protocols and software, a digital infrastructure of the German herbaria will be compatible with international data infrastructures from the very beginning. New developments, e. g. within the framework of DiSSCo currently under development, can be rolled out uniformly in the participating systems and integrated into the existing infrastructure. The resulting services will therefore make a valuable contribution to the national and international "data space" of natural history collections. With the recently published documents under the EU-project "Innovation and consolidation for large scale digitization of natural heritage” (ICEDIG)*

Storage and archiving

With the overall digitization of German herbaria, a common and coherent approach to the management and preservation of approximately 20 million digital herbarium images is required. For the long-term archiving of raw images, the capacities and expertise of existing institutions should be used. One option would be to archive the data in a EUDAT data center located in Germany, which offers standardized services for uploads and integrity tests. The archiving process must be decoupled from continuous digitization, so that, for example, in the event of temporary network failures or bandwidth restrictions, digitization can continue. This is achieved by setting up sufficient local buffer memory. A suitable calibration of the upload process must be carried out in cooperation with the data center on the basis of the existing technical framework conditions. In a Data Management Plan (DMP) agreed between the collections and data centers involved, it is also defined which files are generated during digitization, which files are archived permanently, and which files are temporary and can be deleted if they no longer fulfil a function in the digitization process. Fast access to the archived image data will not be required. Textual label data and any further specimen assigned (meta) data (enriched data) might be processed and archived following data pipelines as currently implemented by the GFBio collection data centers*

A reduced file size of approx. 10 MegaByte (MB) per image corresponds to an image resolution that allows to identify most of the morphological diagnostic features used in identifying organisms to species level or assessing traits (e.g. indumentum, glands) that can be discerned in such an image. The storage of the entire digital stock of German herbaria for access would therefore mean a demand of well below 500 TeraByte (TB). Consequently, a network of 2 to 4 synchronized copies of the entire data stock, operated by the participating research institutions and provided for fast access, would be possible. Should larger file sizes be required in future years, these can be generated at any time from the long-term archived raw data. This ensures that future image resolution requirements can be met. This storage infrastructure requires the development of synchronization and load-balancing mechanisms as well as the implementation of a service interface designed to integrate the data into research workflows. Cooperation with comparable developments in the context of the DiSSCo initiative is sought.

Use Cases for an Infrastructure of Botanical Collections in Germany (and Beyond)

Full digital access to specimens in German herbaria and associated data in a common data infrastructure will offer a data resource that opens up research opportunities and applications in various fields of basic and applied sciences (

Botanical collections in Germany have the capacity to demonstrate the utility of a completely digitized collection type by addressing urgent scientific and societal questions and by developing innovative formats for teaching, outreach and citizen participation. We showcase some examples here.

-

Biodiversity discovery and research: A digital infrastructure of botanical collections will accelerate the discovery and description of species (

Bebber et al. 2010 ). In the face of rapid species loss, it is necessary to accelerate and streamline taxonomic workflows. Models for a collaborative, data-based approach to tackle the taxonomic impediment do exist (e.g.Borsch et al. 2015 ,Kilian et al. 2015 ), but they depend on the availability of digital specimen information and associated data and objects, such as images, sequence data, georeferences, traits and more. Taxonomy as the science of discovering, describing and documenting the diversity of organisms, elucidating their phylogenetic relationships, detecting morphological and molecular (diagnostic) characters and providing valid names, is fundamental to all subsequent research on organisms. The German Research Foundation established the Priority Program “Taxon-Omics: New Approaches for Discovering and Naming Biodiversity” (SPP 1991)*32 for a six year period. A major task in this program is the “Efficient or novel use of natural history collections through automated image analysis, genetic or genomic data from historic specimens or living collections, or new ways of comparing and quantifying traits”. In the first phase of the priority program, altogether eleven projects focused on plants, fungi, lichens or algae, highlighting the importance of Botanical collections*33 . Taxonomists must be provided with cutting-edge data infrastructures and analysis tools to tackle the taxonomic impediment, and the German herbaria will make a major contribution to this goal. Through better accessibility, German collections will be used more extensively by the global scientific community, thus improving their scientific value and the level of scientific treatment. -

Biomonitoring and conservation planning: Digitized herbarium specimens serve as tools for quality control of biomonitoring activities (

Geiger et al. 2016 ). Cross-checking of species identification against reliably identified specimens is key, especially if taxonomically difficult groups are concerned. Digital approaches such as virtual herbaria (e.g. Virtuelles Herbarium der Lausitz*34 or specialised portals for challenging taxa*35 (Dressler et al. 2017 ) allow for greatly enhanced accessibility and new options for data presentation. Digital collections thus constitute references for morphological and molecular reference libraries, and in connection with relevant information, such as indicator values or extinction risk, they can be used to create tools such as checklists, taxonomic monographs or factsheets for biomonitoring purposes. The use of digitized diatoms in factsheets about water quality assessment (Kasten et al. 2018 ) is an applied example from the world of microscopic collections, which may be worthwhile including as a special collection prototype into a digital infrastructure of botanical collections in Germany. In addition, herbarium specimens are an important source of information for documenting floristic changes (e. g.Wörz and Thiv 2015 ), as it can be seen in the recent checklist and red list of vascular plants in Germany (Metzing et al. 2018 ). -

Forecasts about biodiversity development: Niche modelling uses the wealth of data coming with digitization of specimens to create forecasts about biodiversity and biodiversity changes (

Greve et al. 2016 ,Pinkernell and Beszteri 2014 ,de Menezes et al. 2018 ). This powerful tool links to the current debate about biodiversity decline. Before a species becomes extinct, it suffers a gradual, often undetected loss of its populations. Herbarium data, with their depth in space and time, are a valuable data source to create and validate respective models – if they are digitally available and comprehensively exploitable. -

Generation of molecular and other trait information: Extraction of DNA and generation of nucleotide sequence data is by far the most frequent invasive investigation performed on herbarium specimens. These data provide the basis for phylogenetic and phylogenomic biodiversity research (

Bakker 2018 ) and provide new identification tools (Kress et al. 2005 ,Geiger et al. 2016 ). Digitized herbarium specimens play a dual critical role in this process: They have to be explored digitally in order to find the material to close the gaps in the molecular tree of life – and they are an indispensable basis for documentation and unambiguous identification. DNA sequence information is of limited value, unless linked, ideally in a digital fashion, to a specific specimen it has been derived from. In this context, it should also be mentioned that digital specimens are a prerequisite of linking legal documents to genetic resources and thus constitute an important component of implementation of e. g. the Nagoya Protocol (Stevens et al. 2019 ). Regarding molecular and chemical traits, the role of botanical living collections should also be highlighted here. By linking different botanical collection types (e. g. herbarium, living collections, BioResource Centres, DNA-banks, seed banks), an even more comprehensive, well-documented and sustainable research resource can be created. This is especially relevant in plants, algae and fungi for which the use of many "omics" methods requires living organisms which should be curated under consistent workflows with derived permanently preserved objects (i.e. a herbarium specimen linked to a plant in a living collection or seed bank). We refer for example to the national network of Botanical living collections Gardens4Science*24 , which makes living collections in Botanic Gardens available as a living research resource. Likewise, some fungi can be simultaneously preserved both as a herbarised specimen and metabolically inactive culture, so that information on both phenotypic traits and genetic properties will be available for future studies (e.g.Spirin et al. 2017 ). Last but not least, all generated trait data, when linked back to digital specimens, enhance the data pool and allow more and more sophisticated data driven research approaches (e. g.Lauterbach et al. 2019 ). -

Using artificial intelligence for biodiversity research and collection curation: Digitized specimens in large numbers are a unique resource for training data and analysis by image recognition techniques. This includes taxon recognition (

Carranza-Rojas et al. 2017 ,Younis et al. 2018 ), e. g. for incoming material and error detection. It also can be applied for recognition of qualitative morphological traits (Younis et al. 2018 ) as well as measurement of quantitative traits (Gaikwad et al. 2019 ). -

Automated pathogen detection: Plant pests and pathogens can be detected in herbarium specimens (

Böllmann and Scholler 2006 ,Lees et al. 2011 ,McCain and Hennen 1986 ), and available digital images are an important source of knowledge. Crop diseases threat global food security. Fast and accurate pathogen detection is of high economic importance in agri- and horticulture. Digital images can be used by phytopathologists in two ways. First, reference material containing properly identifed plant pests or pathogens (viruses, bacteria, fungi, insects) creates a solid basis for deep machine learning tools. Trained on public image datasets neural networks achieved high accuracy of plant disease detection (e. g.Mohanty et al. 2016 ,Ramcharan et al. 2017 ). Second, trained on reference datasets, tools can be used to analyse retroactively the distribution of plant pathogens, their host spectrum and the diversity of symptoms. -

Facilitating straightforward contextualisation of specimens: In the course of biographical or historical research it may be necessary to link objects of different kinds that may be stored in different collections with publications or even unpublished documents (letters, diaries). In historical times, during their expeditions, botanical explorers not only collected plant specimens but also e.g. shells, coins, artifacts, photographs, geological objects and geographical information. In an ongoing interdisciplinary project we demonstrate the added value of virtually interlinking these classes of objects*

36 . Obviously this will be possible only when the relevant objects are available in digitized manner. In this spirit, European natural history collections are increasingly made available to the digital infrastructure Europeana Collections*37 through the OpenUp! network*38 , which was significantly driven by the Botanical community. -

Enabling provenance research: Exploring the cultural history of natural history collections sheds light on the circumstances under which organisms from nature have been transformed into objects through the work of scientists and thus gain their value through connected data. However, localization of specimens in geographical and historical contexts requires digital access paths independent from the taxonomic storage systems of physical objects. Provenance research has gained increasing attention in colonial contexts mainly for cultural history collections, but is also of interest for natural history collections (e. g.

Rahemipour 2018 ,Timler and Zepernick 1987 ). Working towards an eye-sight collaboration between countries, the botanical community has been proactive towards balancing asymmetries between developing and industrialized nations through fostering access to collections and by committing to the fair sharing of benefits arising from the utilisation of genetic resources, as required by the convention on biological diversity. -

Education, outreach and citizen science: Digitizing collections increases their value for purposes of outreach and education. The Digiphyll*

39 project, for example, links fossil plant species to their extant relatives – it offers an identification key for fossil leaves and makes their images digitally available. The portal is designed for students of palaeontology, but also for schools and the general public, because it provides a wealth of appealing information about the fossil plants. The portal links to the accessions of extant relatives of these fossil plants in the Botanic Garden of Hohenheim and thus attracts students and the interested public to both the digital and the real collections and it is an example for the added value of linking different collection types. The high potential of herbaria for citizen science initiatives is illustrated by the project 'Die Herbonauten'*40 , where a highly committed community has formed in the service of science.

Feasibility

The rate of herbarium specimen digitization and the time needed to fully digitize Germany’s non-digitized herbarium specimens is dependent on factors like digitization equipment, the material to be digitized, on digitization modalities and the availability of trained staff. The community will use synergies for retro-digitization at an industrial scale by creating highly efficient digitization centers particularly beneficial for smaller herbaria, or by making use of commercial digitization centres. Thus all herbaria can train and instruct their staff and prepare their material based on already established, efficient workflows and digitization pipelines and do not have to invest in workflow development on their own. Along with the maturity of the technical concept, clear ideas exist how to prepare for the digitization process and how to manage the new digital collection that will arise. The community has agreed on tasks that are shared between the herbaria and tasks that will remain in the responsibility of the individual collections. For example in GBIF, Germany organised an innovative decentralised model for its contributions, based on the research communities in the country. After a construction project phase, the botanical and mycological GBIF nodes are fully sustained by institutional commitments of the contributing collections. The German GBIF model was further very helpful in the harmonization of data exchange protocols which are currently further developed by GFBio. While the curation of the digital objects and the associated data as well as the responsibility for physical loans has to remain in the responsibility of the institutions (curators), the new central digital infrastructure will

- Provide high-quality data and services for science and society

- Centrally coordinate loans requests

- Organize the continuous digitization of incoming material

- Provide tools for automated data capture

- Facilitate and improve curation of collections by data linkage and online annotation

- Concentrate efforts for storage and archiving

- Implement and improve common taxonomic reference systems

- Share software development and maintenance

- Implement common policies for data provision and use.

All the tools and policies that are already available or will be newly developed are in accordance and compatible with international standards, policies and initiatives like Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG), the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), the efforts around the Distributed System of Scientific Collections (DiSSCo) and its associated projects and the policies and developments of The European Consortium of Taxonomic Facilities (CETAF), which will ensure a seamless integration of the digital infrastructure into larger collection data infrastructures.

Conclusions

We therefore advocate starting the next, most ambitious phase of digitization of German botanical collections with the overall "wall to wall" digitization of the flat objects stored in herbaria, since

- highly efficient industrial processes for high-throughput digitization are available and affordable due to the homogeneous form and can therefore be completed within a manageable framework,

- the greatest possible geographical and taxonomic coverage can be achieved with one object type due to the large number of objects stored in German collections, and

- herbarium collections are particularly suitable for linking further object types and the establishment of a national virtual research collection due to their central role in the research workflows of the institutions as anchors for general collection activities.

German herbarium collections are held by a highly organized community. Complete digitization can be achieved with manageable effort. The digitization process is well-established and the methodology is comparatively easy. The technical infrastructure is developed to a large degree and missing components can be quickly developed within confined projects and in accordance with international standards and initiatives. Mass digitization of standard herbarium specimens will provide the data to support excellent science and to satisfy urgent societal information demands. The digitization of historical and type specimens is a noteworthy example of the first comprehensive set of herbarium specimens that became available at a global level. It has been instrumental for the assessment of plant species diversity and also revolutionized the research process by providing access to specimen information across countries. Moreover, digitization of specimens for the first time opened up their contextualisation within a cultural framwork and such inter- and transdisciplinary approaches for generating novel insights are likely to grow with the development of the semantic web and mass data analyses (see our example use cases). From the beginning, the new infrastructure will contain research results of the German biodiversity informatics community on semantic indexing, cross-collection integration with Linked Open Data, semantic web annotation as well as advanced collaborative taxonomic data processing platforms. In this way, a data space is created that opens up herbaria for a variety of innovative semantics-aware applications. Most importantly, the networked initiative of managing research data in the biological disciplines (GFBio) has already established an integration of data centers (data curation and archiving) with complementary as well as cooperative software development and will certainly be at the forefront of big data analysis in biodiversity. Making a global impact, of course, requires that the data potential of German natural history collections such as herbaria is made available. The authors propose to start this initiative now in order to valorize German botanical collections as a vital part of a worldwide biodiversity data pool.

References

-

Herbarium Genomics: Plant Archival DNA Explored.Population Genomics205‑224. https://doi.org/10.1007/13836_2018_40

-

Herbaria are a major frontier for species discovery.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America107(51):22169‑22171. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011841108

-

GBIF-D and BIOLOG Biodiversity Informatics - the German contribution to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. In: Beck E et al. (Ed.)Sustainable use and conservation of biological diversity - A challenge for society. Proceedings of the International Symposium.Berlin,1-4 Dec 2003.Bonn

-

The Brazil Flora Group: Brazilian Flora 2020: Innovation and collaboration to meet Target 1 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC).Rodriguésia69(4):1513‑1527. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-7860201869402

-

Life cycle and life strategy features of Puccinia glechomatis (Uredinales) favorable for extending the natural range of distribution.Mycoscience47(3):152‑158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10267-006-0282-z

-

An integrative and dynamic approach for monographing species-rich plant groups – Building the global synthesis of the angiosperm order Caryophyllales.Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics17(4):284‑300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2015.05.003

-

Going deeper in the automated identification of Herbarium specimens.BMC Evolutionary Biology17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-1014-z

-

The latitudinal diversity gradient of epiphytic lichens in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest: does Rapoport's rule apply?The Bryologist121(4):480‑497. https://doi.org/10.1639/0007-2745-121.4.480

-

Towards an integrated biodiversity and ecological research data management and archiving platform: The German Federation for the curation of Biological data (GFBio).In: Plöderer E, Grunske L, Schneider E, Ull D (Eds)Informatik 2014 – Big Data Komplexität meistern. GI-Edition: Lecture Notes in Informatics (LNI). Proceedings.232.Köllen-Verlag,Bonn,1711-1724pp.

-

A benchmark dataset of herbarium specimen images with label data.Biodiversity Data Journal7:e31817. https://doi.org/10.3897/bdj.7.e31817

-

Comprehensive and reliable: a new online portal of critical plant taxa in Germany.Plant Systematics and Evolution303(8):1109‑1113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-017-1419-6

-

The Global Genome Biodiversity Network (GGBN) Data Portal.Nucleic Acids Research42(Database issue):607‑612. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt928

-

The importance of herbaria.Plant Science Bulletin49:94‑95.

-

Measuring Morphological Functional Leaf Traits From Digitized Herbarium Specimens Using TraitEx Software.Biodiversity Information Science and Standards3https://doi.org/10.3897/biss.3.37091

-

How to tackle the molecular species inventory for an industrialized nation-lessons from the first phase of the German Barcode of Life initiative GBOL (2012-2015).Genome59(9):661‑70. https://doi.org/10.1139/gen-2015-0185

-

The DNA bank network: the start from a german initiative.Biopreservation and Biobanking9(1):51‑55. https://doi.org/10.1089/bio.2010.0029

-

Realising the potential of herbarium records for conservation biology.South African Journal of Botany105:317‑323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2016.03.017

-

Stable identifiers for collection specimens.Nature546(7656):33‑33. https://doi.org/10.1038/546033d

-

The BioCASE Project - a biological collections access service for Europe. In: Walisch T (Ed.)Proceedings of the first international recorder conference.Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle, Luxembourg,2.-3.12.2005.

-

Actionable, long-term stable and semantic web compatible identifiers for access to biological collection objects.Database2017:bax003. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/bax003

-

Developing integrated workflows for the digitisation of herbarium specimens using a modular and scalable approach.ZooKeys209:93‑102. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.209.3121

-

Digitization and the future of natural history collections.PeerJhttps://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.27859v1

-

Building compatible and dynamic character matrices – Current and future use of specimen-based character data.Botany Letters165:352‑360. https://doi.org/10.1080/23818107.2018.1452791

-

Global Biodiversity Informatics Outlook: Delivering biodiversity knowledge in the information age.Global Biodiversity Information Facilityhttps://doi.org/10.15468/6JXA-YB44

-

The ABCD of primary biodiversity data access.Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology146(4):771‑779. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2012.740085

-

Steckbriefe der Phytoplankton-Indikatortaxa in den WRRL-Bewertungsverfahren PhytoSee und PhytoFluss mit Begleittext – 1. Lieferung: 50 Steckbriefe ausgewählter Indikatortaxa.Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin177. https://doi.org/10.3372/spi.01

-

B-HIT - A Tool for harvesting and indexing biodiversity data.PLOS One10(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142240

-

Sample data processing in an additive and reproducible taxonomic workflow by using character data persistently linked to preserved individual specimens.Database2015:bav094. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/bav094

-

Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences102(23):8369‑8374. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0503123102

-

Accelerating the discovery of biocollections data.GBIF Secretariat,Copenhagen. URL: http://www.gbif.org/resource/83022

-

Using herbaria to study global environmental change.New Phytologist221:110‑122. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15401

-

Variation in leaf anatomical traits relates to the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in Tribuloideae (Zygophyllaceae).Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics39https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2019.125463

-

The French Muséum national d’histoire naturelle vascular plant herbarium collection dataset.Scientific Data4(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.16

-

Tracking origins of invasive herbivores through herbaria and archival DNA: the case of the horse‐chestnut leaf miner.Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment9(6):322‑328. https://doi.org/10.1890/100098

-

Flora Brasiliensis.Missouri Botanical Garden,St. Louis.

-

Collection of plant materials damaged by pathogens: An expression of support.TAXON35(1):119‑121. https://doi.org/10.2307/1221045

-

Lightweight Information Describing Objects (LIDO): The international harvesting standard for museums.Repro Stampa Ind. Grafica,Rome.

-

The unrealised potential of herbaria for global change biology.Ecological Monographs88(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1307

-

Rote Liste gefährdeter Tiere, Pflanzen und Pilze Deutschlands.7.Bundesamt für Naturschutz,Bonn-Bad Godesberg. [ISBN978-3-7843-5612-9]

-

Using Deep Learning for Image-Based Plant Disease Detection.Frontiers in Plant Science7https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01419

-

Potential effects of climate change on the distribution range of the main silicate sinker of the Southern Ocean.Ecology and Evolution4(16):3147‑3161. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1138

-

Bipindi - Berlin. Ein wissenschaftshistorischer und künstlerischer Beitrag zur Kolonialgeschichte des Sammelns.Kosmos Berlin - Forschungsperspektive Sammlungen,1.BGBM Press,Berlin,104pp. [ISBN978-3-946292-29-6]

-

Deep learning for image-based cassava disease detection.Frontiers in Plant Science8https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01852

-

The GBIF integrated publishing toolkit: facilitating the efficient publishing of biodiversity data on the internet.PLOS One9(8):e102623. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102623

-

The Natural History Museum Data Portal.Database : the journal of biological databases and curation2019https://doi.org/10.1093/database/baz038

-

Studies in the Phaeotremella foliacea group (Tremellomycetes, Basidiomycota).Mycological Progress17(4):451‑466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-017-1371-4

-

Documentation of specimens at the Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin with regard to ABS.BGjournal3(1):22‑25.

-

AnnoSys—implementation of a generic annotation system for schema-based data using the example of biodiversity collection data.Database (Oxford)2017(1):bax018. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/bax018

-

The world's herbaria 2018: A summary report based on data from Index Herbariorum. http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/docs/The_Worlds_Herbaria_2018.pdf. Accessed on: 2019-11-18.

-

German Colonia Botany.Berichte der Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft100:143‑168.

-

Diversity Workbench – A virtual research environment for building and accessing biodiversity and environmental data. https://diversityworkbench.net. Accessed on: 2019-10-09.

-

History of exsiccatal series in cryptogamic botany and mycology as reflected by the web-accessible database of exsiccatae "IndExs – Index of Exsiccatae". In: Döbbeler P, Rambold G (Eds)Contributions to Lichenology. Festschrift in Honour of Hannes Hertel. Biblioth. Lichenol.88.739pp.

-

Pilzherbarien – Neue Aufgaben im Bereich Biodiversitätsinformatik und Datenmanagement. In: Bayerische Akademie der WissenschaftenRundgespräche der Kommission für Ökologie, Ökologische Rolle von Pilzen.Bd. 37.München,158pp.

-

Sammlungsschätze online – Schritte zur Virtuellen Naturhistorischen Sammlung.Natur im Museum. – Mitteilungen der Fachgruppe Naturwissenschaftliche Museen im Deutschen Museumsbund4:31‑35.

-

AnnoSys – an online tool for sharing annotations to enhance data quality.Proceedings of TDWG1https://doi.org/10.3897/tdwgproceedings.1.20315

-

Darwin Core: An Evolving Community-Developed Biodiversity Data Standard.PLOS One7(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029715

-

The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship.Scientific Data3(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

-

Bericht zur wissenschaftsgeleiteten Bewertung umfangreicher Forschungsinfrastrukturvorhaben für die Nationale Roadmap.Drs. 6410-1.Wissenschaftsrat,Köln.

-

The temporal dynamics of a regional flora - the effects of global and local impact.Flora217:99‑108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2015.09.013

-

Taxon and trait recognition from digitized herbarium specimens using deep convolutional neural networks.Botany Letters165:377‑383. https://doi.org/10.1080/23818107.2018.1446357

Partners: Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin (MfN, Coordination); Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig (DSMZ); Freie Universität Berlin, Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin (BGBM), Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (SGN); Staatliche Naturwissenschaftliche Sammlungen Bayerns, München (SNSB); Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Stuttgart (SMNS); Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander König, Bonn (ZFMK).