|

Research Ideas and Outcomes : Workshop Report

|

|

Corresponding author: David C. Rose (dcrose100@gmail.com)

Received: 18 Sep 2017 | Published: 21 Sep 2017

© 2017 David Rose, Prue Addison, Malcolm Ausden, Leon Bennun, Craig Mills, Stephanie O’Donnell, Caroline Parker, Melanie Ryan, Lauren Weatherdon, Katherine Despot-Belmonte, William Sutherland, Rebecca Robertson

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: Rose DC, Addison P, Ausden M, Bennun L, Mills C, O’Donnell SAL, Parker C, Ryan M, Weatherdon L, Despot-Belmonte K, Sutherland WJ, Robertson RJ (2017) Decision support tools in conservation: a workshop to improve user-centred design. Research Ideas and Outcomes 3: e21074. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.3.e21074

|

|

Abstract

A workshop held at the University of Cambridge in May 2017 brought developers, researchers, knowledge brokers, and users together to discuss user-centred design of decision support tools. Decision support tools are designed to take users through logical decision steps towards an evidence-informed final decision. Although they may exist in different forms, including on paper, decision support tools are generally considered to be computer- (online, software) or app-based. Studies have illustrated the potential value of decision support tools for conservation, and there are several papers describing the design of individual tools. Rather less attention, however, has been placed on the desirable characteristics for use, and even less on whether tools are actually being used in practice. This is concerning because if tools are not used by their intended end user, for example a policy-maker or practitioner, then its design will have wasted resources. Based on an analysis of papers on tool use in conservation, there is a lack of social science research on improving design, and relatively few examples where users have been incorporated into the design process. Evidence from other disciplines, particularly human-computer interaction research, illustrates that involving users throughout the design of decision support tools increases the relevance, usability, and impact of systems. User-centred design of tools is, however, seldom mentioned in the conservation literature. The workshop started the necessary process of bringing together developers and users to share knowledge about how to conduct good user-centred design of decision support tools. This will help to ensure that tools are usable and make an impact in conservation policy and practice.

Keywords

decision support tools; decision support systems; evidence-based conservation; science-policy; science-practice; technology; user-centred design

Introduction

Evidence-based decision-making is vital to the successful conservation of biodiversity in policy and practice (

Academics and the wider conservation community are now increasingly designing such systems for practitioners (

From an analysis of the papers reviewed by Bagstad et al. (2013) and more recent work on tool use in conservation (e.g.

Lack of knowledge about how to do user-centred design has been highlighted in several papers (

The existing knowledge and practice of user-centred design: a pre-workshop survey

A pre-workshop survey was filled in by 17 delegates. Noting the small sample size, and the likelihood of self-selection (i.e. those attending may have been more interested in user-centred design and thus had practised it before), we asked delegates a number of questions about decision support tools in conservation. 10/17 delegates had used a conservation decision support tool before, mainly in the form of online websites, but paper and software-based tools were also mentioned. As suggested by the literature, respondents raised the issue of low uptake; 50% of those who had tried a conservation decision support tool had never used it again for the following reasons:

- Ambiguity of results

- Lack of benefits to use

- Lack of relevance

- Too expensive

- Too time-consuming

- Lack of evidence-based results

- Complex interface

The survey also asked for experience of designing decision support tools. Eight delegates had designed tools before, with six involving users at a variety of stages, mainly at conception, but also at the design or post-development phase. Designers suggested that user involvement had led to modifications to the user interface and to the content.

Outline of the day

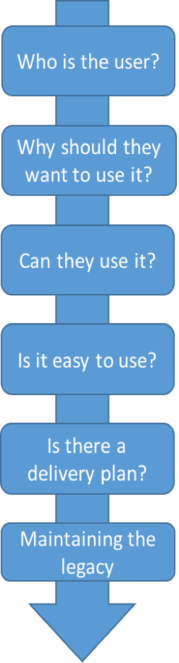

The workshop programme covered the six key steps in good user-centred design outlined by

Talks were structured as follows:

- The importance of user-centred design/matching workflows

- The importance of clear benefits to use

- User testing of tools

- The need for the tool to be easy to use

- Adopting a good delivery plan

- Maintaining tool legacy (see Fig.

1 )

The content and lessons learned in each of the sessions are now discussed. We then discuss how these lessons may inform the future direction of the research and practice of designing decision support tools for conservation.

The importance of user-centred design/matching workflows

Professor Caroline Parker from Glasgow Caledonian University gave a presentation on the importance of user-centred tool design. Distilling 30 years of experience, mainly amassed in the interface between agricultural decision support tools and users, she argued that developers of tools were still not readily including users. A useful thought piece was presented. In it, a group of culinary experts had all the necessary skills to cook a good meal for a client requesting party food; however, the chefs failed to ask about user requirements, and designed a menu completely unsuitable for the intended audience (children’s birthday party not an adult party as they had envisaged). Professor Parker argued that decision support tool development was often done in a similar way by expert designers who had little knowledge about the demands of end users, but nevertheless had a solid conviction that they were able to solve ‘the problem’. She presented results from a structured literature review (see Rose et al., in press) which illustrated that fit to task/workflow was a key component of good user-centred design; in other words, rather than expecting the user to adapt to new tools, a tool was far more likely to be successful if it fit in with existing workflows. A tool should have a clear audience in mind and not be diluted by trying to target multiple groups without understanding the differences between them.

A panel session then discussed how to engage users in tool development. Melanie Ryan (Luc Hoffmann Institute), Stephanie O’Donnell (WILDLABS.NET, FFI), and Dr Prue Addison (University of Oxford), shared their experience of successful user engagement. Ms Ryan spoke about her experience of managing decision support tool design within the Australian Cooperative Research Centres (CRC) Programme, which links research, industry, government and practitioners around multifaceted decision contexts. Dr Addison presented her insights as a NERC Knowledge Exchange fellow at the University of Oxford in which she worked with a variety of clients in the area of decision support (e.g., incorporating biodiversity into business decision-making), whilst O’Donnell offered her insights gained during the establishment of a network of conservationists interested in sharing technology (WILDLABS.NET). They each illustrated the benefits of engaging the user at an early stage, and then throughout the project (even afterwards to evaluate successful uptake of decision-support tools). Reaching out to users by highlighting mutual benefits, and having the empathy required to champion user involvement, were seen as important for a successful stakeholder engagement project. Panellists felt that developers of decision support tools might inadvertently be perceived as deliberately creating a divide between ‘experts’ and users if they did not reach out to their user communities (see Rose et al., in press), failing to recognise that all participants in developing decision support tools have relevant and useful knowledge and expertise. Involving users throughout the project was considered to build trust, allowing users to gain ownership of the project, thereby improving legitimacy, transparency, dissemination and uptake of the tool. Developing a good rapport with users also allow the tool to be improved iteratively by gathering feedback and may help to build an interested user community (see Fig.

Dr Malcolm Ausden, Principal Ecologist at the RSPB, and Dr Leon Bennun from The Biodiversity Consultancy (TBC), shared user perspectives in the context of decision support tools. Both offered an insight into the decision-making process used at both organisations. The RSPB use a variety of different sources of knowledge in management decision-making (see Walsh et al., 2015). The main tool used by TBC is the Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool (IBAT) that brings together key global datasets to help with decision-making about biodiversity (e.g. in relation to development projects). Dr Bennun argued that it was a useful tool since it collated multiple datasets, but some key datasets were missing, and there were some issues with access and cost. Both presenters presented a list of the types of questions posed at the RSPB and The Biodiversity Consultancy on a regular basis, also highlighting potential questions that decision support tools could help with. Dr Ausden argued that day-to-day decision-making on a nature reserve revolved around relatively simple questions, whereas more strategic plans were made at a higher level. Understanding the decision environment is therefore useful for ascertaining where and how a decision support tool might fit in. He also argued that decision support tools needed to be flexible enough to allow practitioners to use other forms of knowledge (e.g. experience & expert judgement) alongside them to form a decision cumulatively, and to allow decisions to also take into account site-specific factors. If tools were designed with user input, therefore, the chances that they would answer important questions would be increased, and so would uptake. Dr Bennun argued that there were few decision-support tools directly tailored to good biodiversity management for industrial-scale projects.

The importance of clear benefits to use

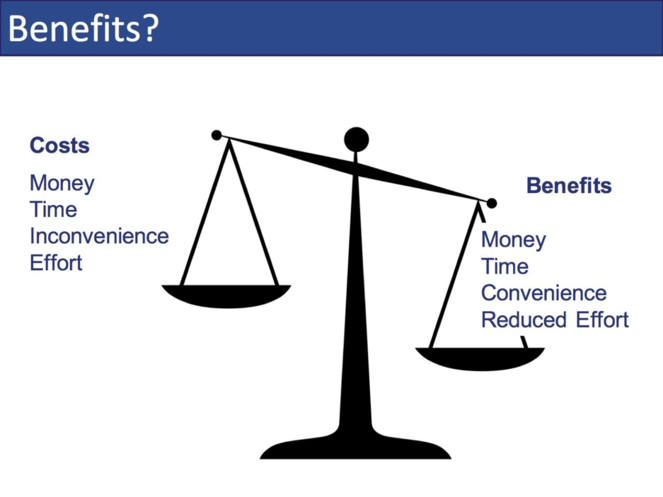

This was a theme touched on by many presenters, but Professor Caroline Parker and Dr Malcolm Ausden offered particularly useful insights. Dr Ausden argued that ‘scientists and conservation practitioners often appear to be operating in parallel universes’, presumably driven largely by the different requirements of journals and conservation practitioners which affected the development of support tools. Tools would often answer scientifically interesting or novel questions, but be poorly suited to the management questions posed by conservation practitioners. As such, tools would be irrelevant and unusable from a practitioner perspective. Professor Parker presented the following figure to explain the importance of highlighting clear benefits to use (see Fig.

Since use of a tool has certain costs to the user (time, effort), benefits must outweigh these costs to make use worthwhile. If a decision could be made in a more efficient way without using a tool, then the tool would be unnecessary. When designing tools, therefore, developers must be clear about highlighting clear benefits to use. This should be a key consideration at the conception phase; if the tool does not improve on current decision-making, or performs a similar role to an existing support tool, then it is not needed.

User testing and ease of use

The themes of ‘can they use it?’ and ‘is it easy to use?’ are similar, but it is important to separate them out. A decision support tool must be usable by the intended end users, otherwise it will not be taken up in practice. Developers must understand the technical knowledge of their end users, whether the necessary infrastructure (e.g. internet) is available in the decision environment, and whether it works every time. More important than the mere ability to use it, the tool must also be easy to use, providing instantaneous answers, without unnecessary hassle. Users are busy and if decision support tools cannot facilitate efficient decision-making, then they will not be used (

The workshop contained a user testing session of eleven decision support tools. Exhibitors of these tools had 15 minutes to display these tools to revolving groups of delegates (over a two-hour period) and feedback on desirable design characteristics was captured in a group discussion session afterwards (see Fig.

User testing of decision support tools. The list of tools exhibited were as follows: (1) Facilitator (Rowan Eisner), (2) Ecobat (Paul Lintott and Sophie Davison), (3) Local Evidence Assessment Tool (Claire Wordley, (4) IBAT (Kerstin Brauneder and Natasha Ali on behalf of IBAT Alliance), (5) Camgeocon (Dilkushi de Alwis Pitts), (6) Species+ (Kelly Malsch), (7) Protected Planet (Brian MacSharry), (8) TradeMapper (TRAFFIC), (9) LEFT (Peter Long), (10) NaturEtrade (Peter Long and Beccy Wilebore), and (11) WCS Offenders database (Andy Plumptre).

Based on their experience of testing tools, delegates proposed several good and bad design features. From a post-workshop survey (n=22), delegates also ranked from 1-10 various design features of decision support tools (based on factors identified by

- Relevance to user – 211 (9.6)

- Benefits to use – 204 (9.3)

- Ease of use – 202 (9.2)

- Trusted evidence-based – 191 (8.7)

- Helps to satisfy existing work requirements (e.g. legislation, targets) – 180 (8.2)

- Cost (affordability) – 173 (7.9)

- Fits user routine – 169 (7.7)

- Matches decision habits – 168 (7.6)

- Integrates with other systems – 168 (6.7)

- Recommended by colleagues – 167 (6.7)

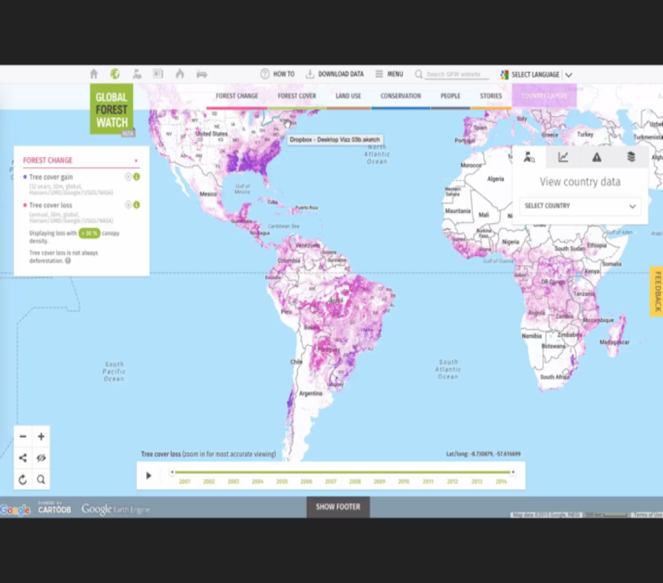

Craig Mills from Vizzuality also offered his key tips for good design, including the use of appealing visualisations and choice of colours, to generate an exciting and attractive user interface. They have an example of Global Forest Watch, pictured below, for which they developed an engaging design. Mills also mentioned the concept of progressive disclosure, in other words a simple interface at a superficial level, but a deeper layer that users can explore if they want to (see Table

Good and bad design features as described by delegates (number in brackets determines no. of mentions).

|

Positive design features |

Negative design features |

|

Ease of use (8) |

Slow or difficult to use (4) |

|

Ability to personalise it/flexibility/relevance for user (8) |

Trying to do too much (3) |

|

Simple language/interface (7) |

Unclear who user is (2) |

|

Fun to use/engaging design (5) |

Unclear output (2) |

|

Clarity over who the user is (5) |

No sense of where underlying data is from (2) |

|

Adaptive/integrated design (4) |

No thought about ongoing maintenance (2) |

|

Allow user feedback (3) |

No unique selling point (1) |

|

Transparent, evidence-based datasets (3) |

Expensive (1) |

|

Incorporate user-testing in design (2) |

Poor reliability (1) |

|

Clear benefits to use (2) |

Complicated language (1) |

|

Good legacy plan (1) |

|

|

Do one thing and do it well (1) |

|

|

Simple user tutorial (1) |

Global Forest Watch had Vizzuality design input (credit: www.globalforestwatch.org).

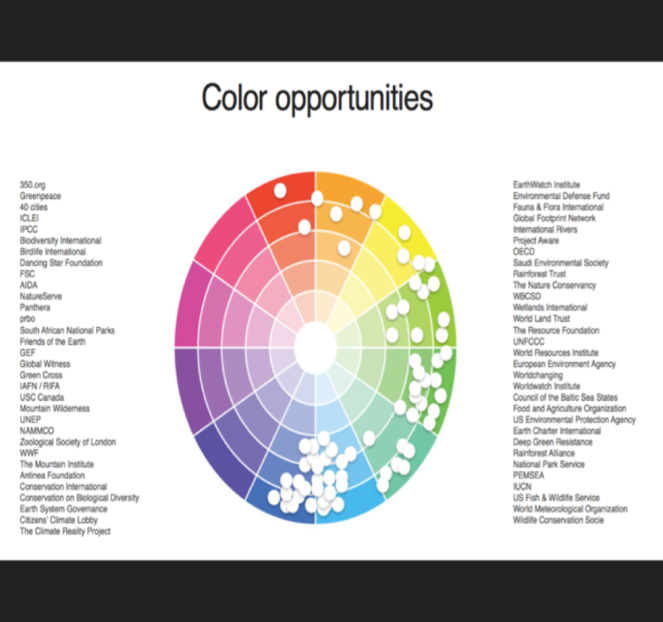

Adopting a good delivery plan

Craig Mills from Vizzuality also gave advice on how to develop a good delivery plan. Delegates agreed that if users did not know that a tool existed, then it could not be used in practice. He argued that conservation organisations tend to adopt the same colour of branding, and therefore alternative colours might help a new tool to stand out from the crowd. In terms of engaging people, Mills suggested that tool developers should aim to convert ‘1000 true fans’ (http://kk.org/thetechnium/1000-true-fans/). These fans would help spread the message, be brand ambassadors, and recommend the tool to others. The key to stimulating user interest is to get people to say nice things about the tool without the developer being in the room. The exhibitors from the World Café session also shared how they had promoted their tools – from organising workshops with end users, to the use of social media, and conference presentations (see Fig.

Maintaining the legacy

Lauren Weatherdon from UNEP-WCMC shared insights on preserving tool legacy, drawn from her own experiences as well as those of Katherine Despot-Belmonte, Corinne Martin, and others at UNEP-WCMC, and from the European Biodiversity Observation Network project. Decision support tools designed by researchers with external funding can quickly become unusable if they are not adequately maintained once funding ends. Weatherdon encouraged designers to create a business plan for their tool at the beginning of the process. She also highlighted several key points to ensure that a tool has longevity (Credit: Weatherdon and Despot-Belmonte):

- Start with a clear and user-driven policy mandate/objective

- Locate your product’s niche within the biodiversity informatics landscape

- Engage in iterative co-design with users throughout the design process

- Develop strategies for ensuring continued capacity (financial; human)

- Reconcile ‘open access’ data with value-added services

- Don’t consult once, and never again!

- Don’t leave it too late to consider your business plan

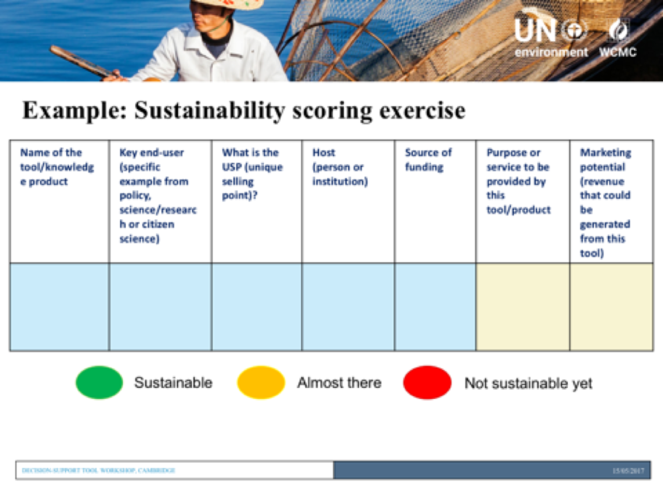

Weatherdon proposed the following scoring exercise, designed by Katherine Despot-Belmonte, to determine the sustainability of a decision support tool, focusing on highlighting the unique selling point, the service provided by the tool, and the marketing potential (i.e. how revenue or partner support could be generated to secure long-term maintenance, see Fig.

Key messages and future research directions

From a post-workshop survey of delegates (n=22) the following take home messages were collected. When developing DSS there is a need to:

- Identify whether there is a demand for the tool, and who the potential end users are.

- Engage users in tool design to ensure that the technology was relevant to user needs.

- Test tools on actual end users rather than like-minded colleagues.

- Link tools to legislative instruments to improve relevance.

- Pay attention to interface design, including engaging colours and simple navigation.

- Consider actively marketing the product, and not to see marketing as a ‘dirty’ word. Users will not know about a tool unless there is a good marketing strategy.

- Think about the long-term legacy of the tool once funding ends. Will it be easy to maintain afterwards and what incentive is there for other people to do it?

We hope to foster greater interest in user-centred design of decision support tools, and one useful next step may be to hold a follow-up workshop sharing principles about how to carry out stakeholder engagement effectively (see

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the University of Cambridge Conservation Research Institute, the Luc Hoffmann Institute, and the European Biodiversity Observation Network (7th Framework Programme funded by the European Union under grant agreement No. 308454) for funding the workshop. We would like to thank all speakers, panelists, exhibitors, and delegates for their contributions to the workshop, and the Cambridge Conservation Initiative for hosting the workshop at the David Attenborough Building in Cambridge. P.F.E.A would like to thank the UK Natural Environmental Research Council for support through the NERC Knowledge Exchange fellowship scheme (NE/L002663/1). We also thank others who have helped with this work including C. Wordley, A. Harvey, B. Vira, and O. Shears. DCR also thanks funding from the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of East Anglia.

References

-

Conservation practitioners' perspectives on decision triggers for evidence-based management.Journal of Applied Ecology53(5):1351‑1357. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12734

-

Towards quantitative condition assessment of biodiversity outcomes: Insights from Australian marine protected areas.Journal of Environmental Management198:183‑191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.04.054

-

Practical solutions for making models indispensable in conservation decision-making.Diversity and Distributions19:490‑502. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12054

-

Are we missing the boat? Current uses of long-term biological monitoring data in the evaluation and management of marine protected areas.Journal of Environmental Management149:148‑156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.10.023

-

A comparative assessment of decision-support tools for ecosystem services quantification and valuation.Ecosystem Services5:27‑39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.07.004

-

Decision triggers are a critical part of evidence-based conservation.Biological Conservation195:46‑51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.12.024

-

Conservation in the dark? The information used to support management decisions.Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment8(4):181‑186. https://doi.org/10.1890/090020

-

Organising evidence for environmental management decisions: a ‘4S’ hierarchy.Trends in Ecology & Evolution29(11):607‑613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.09.004

- https://www.ipbes.net/dataset/thematic-assessment-pollinators-pollination-and-food-production. Accessed on: 2017-9-07.

-

Integrated environmental modeling: A vision and roadmap for the future.Environmental Modelling & Software39:3‑23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.09.006

-

Promoting sustainable intensification in precision agriculture: review of decision support systems development and strategies.Precision Agriculture18(3):309‑331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-016-9491-4

-

Design of a decision support tool for visualising E. coli risk on agricultural land using a stakeholder-driven approach.Land Use Policy66:227‑234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.05.005

-

User-centred design does make a difference. The case of decision support systems in crop production.Behaviour & Information Technology20(6):449‑460. https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290110089570

-

A theory of participation: what makes stakeholder and public engagement in environmental management work?Restoration Ecologyhttps://doi.org/10.1111/rec.12541

-

Biodiversity works.INVALUABLE Working Paper,The Hague,5pp.

-

The social side of spatial decision support systems: Investigating knowledge integration and learning.Environmental Science & Policy76:177‑184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.06.015

-

Decision support tools for agriculture: Towards effective design and delivery.Agricultural Systems149:165‑174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2016.09.009

-

Decision support tools in agriculture: learning lessons for effective user-centred design.International Journal of Agricultural Management.

-

Evidence complacency hampers conservation.Nature Ecology & Evolution1(9):1215‑1216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0244-1

-

The need for evidence-based conservation.Trends in Ecology & Evolution19(6):305‑308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.018

-

Barriers and Solutions to Implementing Evidence-Based Conservation.University of Cambridge[Inunpublished].

-

Blueprints of Effective Biodiversity and Conservation Knowledge Products That Support Marine Policy.Frontiers in Marine Science4https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00096