|

Research Ideas and Outcomes : Review Article

|

|

Corresponding author: Kristina von Rintelen (kristina.rintelen@mfn-berlin.de)

Received: 07 Sep 2017 | Published: 11 Sep 2017

© 2017 Kristina von Rintelen, Evy Arida, Christoph Häuser

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: von Rintelen K, Arida E, Häuser C (2017) A review of biodiversity-related issues and challenges in megadiverse Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries. Research Ideas and Outcomes 3: e20860. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.3.e20860

|

|

Abstract

Indonesia is one of the ten member states of the economically and politically diverse regional organization of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Southeast Asia comprises four of the 25 global biodiversity hotspots, three of the 17 global megadiverse countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines) and the most diverse coral reefs in the world. All member states are Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). We discuss ASEAN-wide joint activities on nature conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity that do not stop at national borders.

The Indonesian archipelago comprises two of the world’s biodiversity hotspots (areas with a high degree of endemic species that are highly threatened by loss of habitats): Its insular character and complex geological history led to the evolution of a megadiverse fauna and flora on the global scale. The importance of biodiversity, e.g., in traditional medicine and agriculture, is deep-rooted in Indonesian society. Modern biodiversity pathways include new fields of application in technology, pharmacy and economy along with environmental policies. This development occurred not only in Indonesia but also in other biodiversity-rich tropical countries.

This review summarizes and discusses the unique biodiversity of Indonesia from different angles (science, society, environmental policy, and bioeconomy) and brings it into context within the ASEAN region. The preconditions of each member state for biodiversity-related activities are rather diverse. Much was done to improve the conditions for biodiversity research and use in several countries, primarily in those with a promising economic development. However, ASEAN as a whole still has further potential for more joint initiatives. Especially Indonesia has the highest biodiversity potential within the ASEAN and beyond, but likewise the highest risk of biodiversity loss.

We conclude that Indonesia has not taken full advantage of this potential yet. A growing national interest in local biodiversity as a natural resource is a welcome development on one hand, but the risk of too many restrictions for, e.g., the science community (high level of bureaucracy at all project stages from planning phase, visa procedures, field work permits, scientific exchange and project managment issues, governmental budget cuts for basic research and restricted access to international literature for Indonesian researchers) does significantly hamper the internationalization of biodiversity-related science. In the long run, Indonesia has to find a balance between protectionism and sensible access to its national biodiversity to tackle global challenges in biodiversity conservation, health issues, food security, and climate change.

Keywords

Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Indonesian archipelago, environmental policy, conservation, biodiversity loss, access and benefit sharing, sustainable use, biodiversity research and education

Introduction

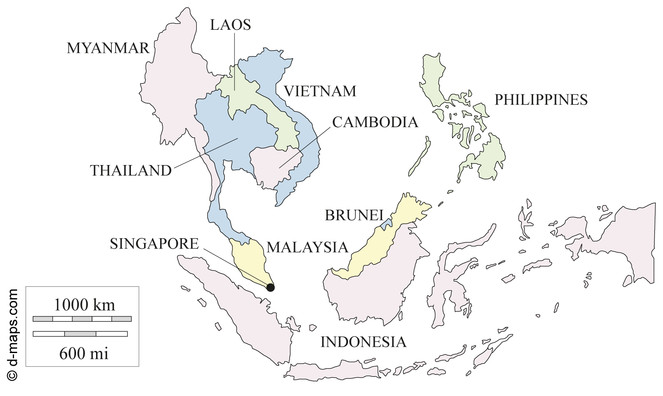

Indonesia is one of the ten member states of the economically and politically diverse regional organization of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Its area covers the tropical countries of Southeast Asia bar East Timor (Fig.

Map of Southeast Asia.

The ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Southeast Asia. The map shows the isolated islands of Indonesia and the Philippines. Their complex biogeographical and geological history led to the evolution of an extraordinary biodiversity and endemism. Map modified from d-maps.com (the original map was downloaded from http://www.d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=28675&lang=en).

Why a focus on Indonesian biodiversity? The Indonesian archipelago comprises 17,000 islands with many different types of habitats and an extremely complicated geological history, although the latter counts not only for Indonesia but for Southeast Asia in general (

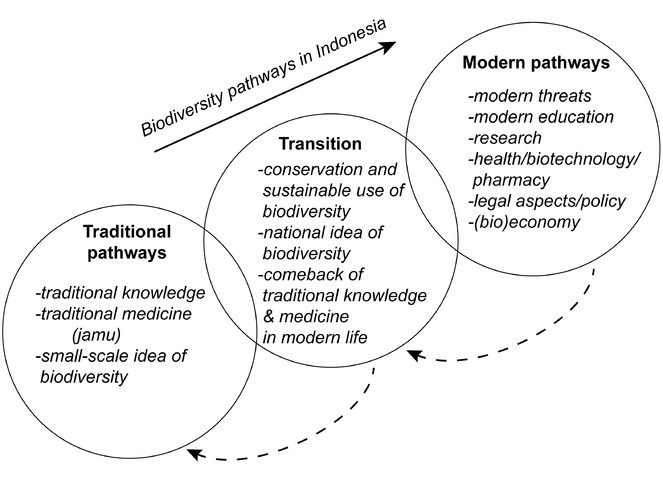

The changing role and pathways of biodiversity in Indonesian society

Biodiversity affects different aspects of Indonesian society. Indonesia is not only megadiverse in terms of biodiversity but also in terms of cultural diversity. The country has about 370 ethnic groups (

The changing pathways of biodiversity in Indonesian society (without any claim of completeness and time scale).

The oldest forms of biodiversity-related knowledge changed over time and (local) space, also from rather bottom-up (local knowledge) to more top-down pathways (e.g., governmental programmes) (continuous line). However, modern pathways also rely on older pathways and the whole process is not only unidirectional (dashed line) as older pathway (traditional knowledge and medicine) are often making a comeback.

The traditional pathways of biodiversity (Fig.

Apart from the national perspective, there are also rather small-scale transitional pathways: Traditional pathways can make a comeback in modern life, such as traditional medicine (jamu) (

In comparison, the modern pathways (Fig.

A biodiversity-related comparison of Indonesia and the other ASEAN member states

We here discuss different approaches to biodiversity in Indonesia and all other ASEAN member states. The following parameters used to compare biodiversity-related data among the ASEAN member states are mainly based on the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity (ACB): National biodiversity data, threatened species, invasive alien species, conservation programmes and ABS (Access and Benefit Sharing) regulations. Furthermore, we compare the research output (publications) on country-specific biodiversity, biodiversity-related infrastructure per country, general economic data, bioeconomy policy strategies and approaches for the sustainable use of biodiversity.

National biodiversity facts and figures

The Convention on Biological Diversity uses the National Biodiversity Index (NBI) to quantify biodiversity in different countries. The NBI estimates country richness and endemism in four terrestrial vertebrate classes and vascular plants, index values range between 1.000 (maximum) and 0.000 (minimum) and includes some adjustment allowing for country size (Suppl. material

Indonesia has the highest NBI of all ASEAN countries, Cambodia the lowest (Suppl. material

It is essential to consider the threats to and loss of biodiversity when looking at biodiversity hotspots as defined by

Invasive species can have negative economic and environmental impacts and are also an increasing threat to biodiversity in Southeast Asia (

Biodiversity-related conservation programmes and ABS regulations

Within the ASEAN region, there are several (national) biodiversity-related policies and conservation initiatives. We here focus on major programmes that exist across all ASEAN member states such as regional protected areas (PAs) including the ASEAN-specific Heritage Parks Programme. Another recent development is the so-called Nagoya Protocol on ABS (Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization): Abundance of biodiversity in the ASEAN region also means abundance of genetic resources. If these genetic resources and the traditional knowledge associated with them are studied and utilized abroad (e.g., from basic biological research to applied research & development), the Nagoya Protocol on ABS applies. As a supplementary agreement to the CBD “it provides a transparent legal framework for […] the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources” (

Suppl. material

However, the IUCN management categories are voluntary for countries to apply and the lack of such does not mean a lack of protected management or biodiversity conservation (

ASEAN Heritage Parks (Suppl. material

All ASEAN countries with a lower middle to low economic situation (Suppl. material

Biodiversity-related research output

Various public (partly national) and private research institutions in the ASEAN region conduct biodiversity-related research. However, there are major differences in research infrastructure and research output per country. One method to compare the research output on local biodiversity is to look at the number of scientific publications on biodiversity-related topics per country in ISI-listed journals (for details see legend of Suppl. material

Generally, the results (for details seeSuppl. material

Biodiversity-related infrastructure within the ASEAN

Biodiversity-related infrastructure within the ASEAN was assessed by counting local institutions with natural history collections, zoological and botanical gardens, herbaria, biobanks, culture and other collections per country (Suppl. material

A possible reason for the high number of biorepositories in Thailand might the high proportion of so-called culture collections (these are repositories of cultures of microorganisms and cultured cells), i.e., 63 culture collections among a total of 86 biorepositories (Suppl. material

A general problem of all biological collections within ASEAN is subtropical or tropical climate with high temperatures, high humidity and lots of potential threats like insect pests and mold. Dry and alcohol-preserved collections need to be air-conditioned and well-maintained. In Indonesia, for instance, with its thousands of islands, this certainly is a challenge, although the problem can be mitigated in important logistic hubs like the area around the capital Jakarta in West-Java with its national collections of the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI).

Bioeconomy and sustainable use of biodiversity

Bioeconomy is a relatively new field of economy. Its aim is the utilization of renewable biological resources and their transformation into sustainable products for industrial purpose, for example, biological pharmaceuticals, biofuels, biosensors (

Indonesia and Germany, for instance, have a long-term cooperation in biotechnology and recently established a cooperation between the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) and several German research institutes in the fields of biodiversity and health sciences (

Biodiversity-related education and capacity building

Within the ASEAN, there are many initiatives on environmental education by schools, universities, governmental research institutions, and various NGOs. As a joint feature, the ASEAN established ASEAN Guidelines on Eco-Schools for environmentally friendly model schools in the region in order to raise environmental awareness in every aspect of the education system (

A classical scientific approach to biodiversity is taxonomy, i.e., the identification, description and classification of organisms. It is the basic precondition for conservation and sustainable use of our biotic environment. Taxonomic capacity building is thus essential to secure biodiversity-related knowledge for future generations. Just to name one ASEAN specific initiative, the ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity is frequently holding workshops on taxonomy (

In the framework of capacity building, there are a number of bilateral exchange programmes with ASEAN member states. For example, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) is active in all ten countries. Currently, Indonesia started a biodiversity-related exchange programme with Germany focusing on the innovative discovery and conservation of biodiversity in the framework of “Biodiversity & Health” (DAAD 2016).

Conclusions and challenges for Indonesian and Southeast Asian biodiversity

Indonesia is a megadiverse country. Its special insular nature along with the high number of endemic species vs. a high number of threatened species and a high number of invasive alien species make the country more vulnerable to negative impacts than any other Southeast Asian country. Other key drivers of biodiversity loss such as deforestation and habitat loss are continuing in Indonesia, and are similarly fatal. The long-term destruction of the huge carbon storage ecosystems on Sumatra and Kalimantan are certainly among the bigger challenges, not to mention the transboundary haze pollution caused by forest and peat fires (

In terms of biodiversity conservation, Indonesia has one of the highest numbers of protected areas within the ASEAN and the highest number when applying IUCN categories. Nevertheless, compared to a global scale (for instance, this becomes already obvious when only compared to Brazil and Germany), Indonesia still has a high potential for more PAs. Another great potential is biodiversity-related research of various disciplines, from basic taxonomy (identification, description, and classification of organisms) to applied biotechnology and pharmacy. Another key factor is the sustainable use of its numerous biological resources, for example for human health, food security and bioeconomy. Indonesia is one of the few ASEAN member states that have developed a bioeconomy policy strategy. In 2015, Indonesia launched a new Indonesian Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (IBSAP 2015-2020;

Indonesia was one of the first countries worldwide to sign the Nagoya Protocol (NP) when it was open to signature (May 2011), ratified it in September 2013 and its party status entered into force in October 2014 (

The international scientific community is well aware of Indonesia’s extraordinary biodiversity and its infrastructure is generally well-suited for biodiversity-related research. A good number of comparatively well-equipped research institutions exist throughout the country for this purpose. Unsurprisingly perhaps, no other Southeast Asian country has more publications on their respective natural environment. On the other hand, Indonesia showed a higher discrepancy between international and national biodiversity-related research output (almost 60% of publications lack authors from Indonesian institutes) than other countries with a similarly rich biodiversity. In other words, there is a high potential for local researchers to get their share of the international cake. So, what is the reason for this discrepancy and what can one do to take full advantage of this potential?

Currently, there is rising concern in Indonesia’s biodiversity research community over recent financial cuts from the government as well as the fact that the application process for foreign research permits in Indonesia is complicated and time-consuming (see review in

In order to realize its full research potential, Indonesia needs to increase profit from international collaborations and equally strengthen biodiversity interest groups at the national level. For example, it could reach out regionally by linking Indonesian natural history collections, collaborate with museums and herbaria in western countries to get better access to historic collections by making them available online (digitization), and strengthen capacity building in taxonomy and access to international literature in science.

In conclusion, Indonesia has a very high if not the highest biodiversity potential within the ASEAN region. It needs to fully capitalize on this huge potential through targeted and strategic investments in its national scientific and educational capacities to allow long-term value out of its biodiversity for the country – time will tell if the new national biodiversity strategy and action plan might be a further step forward. Due to the highly international and globally connected research and R&D in life sciences in general, the country needs to become more open and engaging in international cooperation, as no single country will be able to successfully master this challenge on its own.

Megadiverse countries like Indonesia, the Philippines or Brazil have a worldwide effect by influencing climate, bioresources, human well-being and health on a larger scale. Generally, there is a high potential for further joint biodiversity-related activities for all ASEAN member states despite different preconditions in economy, infrastructure and environmental policies. Biodiversity does not stop at national borders and there are general environmental threats all ASEAN member states have to face. Although a lot has been done already, it is worth keeping track of biodiversity-relevant political, economic and scientific developments in the region.

Overall, Indonesia’s scientific output would greatly benefit from increased internationalization and further capacity building. The bureaucratic obstacles for foreign and local researchers in the country are still high (high level of bureaucracy at all project stages from planning phase, visa procedures, field work permits, scientific exchange and project managment issues, governmental budget cuts for basic research and restricted access to international literature for Indonesian researchers) along with a steadily growing protectionism of its national biodiversity that could hamper the internationalization of science. In the long run, Indonesia has to find a balance between protectionism and sensible access to its national biodiversity to tackle global challenges in science and technology, health issues, food security, and climate change.

Acknowledgements

The idea for this review came from a 6-months feasibility study on biodiversity facilities in Asian countries funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the International Bureau (IB) in Germany. Further aspects and results were incorporated from a 1-year pilot study on Indonesian biodiversity and the sustainable utilization of natural active compounds (BMBF grant number 16GW0032) plus the ongoing research project IndoBioSys (Indonesian Biodiversity and Information System; BMBF grant number 16GW0111K) within the German-Indonesian G2G programme “Biodiversity and Health – from biodiscovery to biomedical innovation”. We further thank Thomas von Rintelen, Luis Valente (both MfN Berlin, Germany), Michael Balke (ZSM Munich, Germany), Hendrik Freitag (Ateneo de Manila University, Philippines) and Andreas Wessel (Germany) for valuable comments on the manuscript.

References

-

The Access and Benefit-Sharing Clearing-House (ABSCH) by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. https://absch.cbd.int. Accessed on: 2016-10-06.

-

ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity: ASEAN Biodiversity Outlook.Dolmar Press, Inc., Philippines,208pp. [ISBN978-971-94164-4-9]

-

ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity: ASEAN Heritage Parks as of December 2015. http://chm.aseanbiodiversity.org. Accessed on: 2016-10-06.

-

ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity: One ASEAN. One Biodiversity. http://www.aseanbiodiversity.org. Accessed on: 2016-9-15.

-

ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity: ASEAN to hold taxonomy training in Indonesia. http://aseanbiodiversity.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=290:asean-to-hold-taxonomy-training-in-indonesia-&catid=1:news&Itemid=109. Accessed on: 2016-11-07.

-

ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity: ASEAN Biodiversity Events. http://aseanbiodiversity.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=12&Itemid=104¤t=102. Accessed on: 2016-11-07.

-

The role of traditional knowledge and access to genetic resources in biodiversity conservation in Southeast Asia.Biodiversity and Conservation19(4):1189‑1204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-010-9816-y

-

ASEAN Cooperation on Nature Conservation and Biodiversity. http://environment.asean.org/asean-working-group-on-nature-conservation-and-biodiversity/. Accessed on: 2016-10-14.

-

ASEAN Cooperation on Environmental Education. http://environment.asean.org/asean-cooperation-on-environmental-education/. Accessed on: 2016-10-14.

-

Indonesian Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan – National Document. The National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS), Jakarta. https://www.cbd.int/countries/?country=id. Accessed on: 2016-10-11.

-

Indonesian Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (IBSAP) 2015-2020. The National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS), Jakarta. http://www.bappenas.go.id/id/profil-bappenas/unit-kerja/deputi-bidang-sumber-daya-alam-dan-lingkungan-hidup/direktorat-lingkungan-hidup/contents-direktorat-lingkungan-hidup/indonesian-biodiversity-strategy-and-action-plan-ibsap-2015-2020/. Accessed on: 2017-2-17.

-

Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung / Federal Ministry of Education and Research Germany (BMBF). Deutsch-indonesische Kooperation für Wirkstoffforschung. http://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/de/5263.php. Accessed on: 2016-11-07.

-

Borneo and Indochina are Major Evolutionary Hotspots for Southeast Asian Biodiversity.Systematic Biology63(6):879‑901. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syu047

-

Indonesia: Policies and Biodiversity. In: Lutz E, Caldecott J (Eds)Decentralization and Biodiversity Conservation. A World Bank Symposium.The World Bank,Washington, D.C.,43-53pp.

-

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD): List of Parties. https://www.cbd.int/information/parties.shtml. Accessed on: 2016-9-22.

-

Indonesia – Country Profile: Biodiversity Facts. https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/default.shtml?country=id#facts. Accessed on: 2016-9-22.

-

About the Nagoya Protocol. https://www.cbd.int/abs/about/default.shtml. Accessed on: 2016-10-04.

-

Biodiversity, cultural pathways, and human health: a framework.Trends in Ecology & Evolution29(4):198‑204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.01.009

-

Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst / German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). DAAD’s „Biodiversity & Health“ Programme. http://daadjkt.org/index.php?daads-biodiversity-and-health. Accessed on: 2016-11-07.

-

Biodiversity indicators: the choice of values and measures.Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment98:87‑98. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8809(03)00072-0

-

Jamu: Indonesian traditional herbal medicine towards rational phytopharmacological use.Journal of Herbal Medicine4(2):51‑73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hermed.2014.01.002

-

More strictly protected areas are not necessarily more protective: evidence from Bolivia, Costa Rica, Indonesia, and Thailand.Environmental Research Letters8(2):025011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/025011

-

Bioeconomy Policy (Part II) – Synopsis of National Strategies around the World. A report of the German Bioeconomy Council. http://biooekonomierat.de/fileadmin/international/Bioeconomy-Policy_Part-II.pdf. Accessed on: 2017-2-08.

-

The use of various plant types as medicines by local community in the enclave of the Lore-Lindu national park of Central Sulawesi, Indonesia.Global Journal of Research on Medicinal Plants & Indigenous Medicine5(1):29‑40.

-

Bioeconomy Policies around the World. http://biooekonomierat.de/biooekonomie/international. Accessed on: 2016-10-05.

-

Measuring biodiversity performance: A conditional efficiency measurement approach.Environmental Modelling & Software25(12):1866‑1873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.04.014

-

Access to Genetic Resources in Indonesia: Need Further Legislation?Oklahoma Journal of Law and Technology79:1‑19. URL: http://www.law.ou.edu/sites/default/files/files/FACULTY/latifah%20final%20version%202.pdf

-

Toward clearer skies: Challenges in regulating transboundary haze in Southeast Asia.Environmental Science & Policy55:87‑95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.09.008

-

Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia/Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI). http://lipi.go.id. Accessed on: 2016-10-12.

-

Indonesia – Germany Agree to Enhance Cooperation on Biodiversity and Health Sciences Sector. Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia/Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Bureau of cooperation, Law and Public Relations. http://lipi.go.id/berita/Indonesia-Jerman-Sepakati-Tingkatkan-Kerjasama-Iptek-Bidang-Biodiversitas-dan-Kesehatan/16531. Accessed on: 2017-10-12.

-

Biogeography of the Indo-Australian Archipelago.Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics42(1):205‑226. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145001

-

Advancing taxonomy and bioinventories with DNA barcodes.Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences371(1702):20150339. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0339

-

Megadiversity: earth’s biologically wealthiest nations.Cemex,Prado Norte, Mexico.

-

Species Identification in Malaise Trap Samples by DNA Barcoding Based on NGS Technologies and a Scoring Matrix.PLOS ONE11(5):e0155497. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155497

-

Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities.Nature403(6772):853‑858. https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501

-

The National Parks Board: Biodiversity. https://www.nparks.gov.sg/biodiversity. Accessed on: 2016-10-05.

-

Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National University of Singapore (NUS). http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg. Accessed on: 2016-10-05.

-

Economic and Environmental Impacts of Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in Southeast Asia.PLoS ONE8(8):e71255. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071255

-

A perspective on education for sustainable development: Historical development of environmental education in Indonesia.International Journal of Educational Development29(6):621‑627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.12.002

-

Indicators for Monitoring Biodiversity: A Hierarchical Approach.Conservation Biology4(4):355‑364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.1990.tb00309.x

-

Biodiversity and Natural Resource Management in Insular Southeast Asia.Island Studies Journal1(1):81‑108. URL: https://www.islandstudies.ca/sites/vre2.upei.ca.islandstudies.ca/files/u2/ISJ-1-1-2006-Persoon-vanWeerd-pp81-108.pdf

-

The Intersections of Biological Diversity and Cultural Diversity: Towards Integration.Conservation and Society7(2):100‑112. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.58642

-

Environmental Ethics in Local Knowledge Responding to Climate Change: An Understanding of Seasonal Traditional Calendar PranotoMongso and its Phenology in Karst Area of GunungKidul, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.Procedia Environmental Sciences20:785‑794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.095

-

A biodiversity intactness index.Nature434(7029):45‑49. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03289

-

Southeast Asian biodiversity: an impending disaster.Trends in Ecology & Evolution19(12):654‑660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.09.006

-

ASEAN Guidelines on Eco-School. http://environment.asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ASEAN-Guidelines-on-Eco-schools.pdf. Accessed on: 2016-9-14.

-

Indonesia launches national blueprint to protect its biodiversity. UNDP Press Releases. http://www.id.undp.org/content/indonesia/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2016/01/21/indonesia-launches-national-blueprint-to-protect-its-biodiversity.html. Accessed on: 2017-2-17.

-

UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK: Biodiversity A-Z website. www.biodiversitya-z.org. Accessed on: 2016-10-07.

Supplementary material

Download file (16.84 kb)