|

Research Ideas and Outcomes :

Forum Paper

|

|

Corresponding author: Jeremy A. Miller (jeremy.miller@naturalis.nl)

Received: 02 Mar 2017 | Published: 06 Mar 2017

© 2017 Willi Egloff, Donat Agosti, Puneet Kishor, David Patterson, Jeremy Miller

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Egloff W, Agosti D, Kishor P, Patterson D, Miller J (2017) Copyright and the Use of Images as Biodiversity Data. Research Ideas and Outcomes 3: e12502. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.3.e12502

|

|

Abstract

Taxonomy is the discipline responsible for charting the world’s organismic diversity, understanding ancestor/descendant relationships, and organizing all species according to a unified taxonomic classification system. Taxonomists document the attributes (characters) of organisms, with emphasis on those can be used to distinguish species from each other. Character information is compiled in the scientific literature as text, tables, and images. The information is presented according to conventions that vary among taxonomic domains; such conventions facilitate comparison among similar species, even when descriptions are published by different authors.

There is considerable uncertainty within the taxonomic community as to how to re-use images that were included in taxonomic publications, especially in regard to whether copyright applies. This article deals with the principles and application of copyright law, database protection, and protection against unfair competition, as applied to images. We conclude that copyright does not apply to most images in taxonomic literature because they are presented in a standardized way and lack the individuality that is required to qualify as ‘copyrightable works’. There are exceptions, such as wildlife photographs, drawings and artwork produced in a distinctive individual form and intended for other than comparative purposes (such as visual art). Further exceptions may apply to collections of images that qualify as a database in the sense of European database protection law. In a few European countries, there is legal protection for photographs that do not qualify as works in the usual sense of copyright. It follows that most images found in taxonomic literature can be re-used for research or many other purposes without seeking permission, regardless of any copyright declaration. In observance of ethical and scholarly standards, re-users are expected to cite the author and original source of any image that they use.

Keywords

Big data, Intellectual property rights, Open Access, Taxonomy

Introduction

Communication is a key part of science. Through access to prior scientific results and through communication of new results, we collectively assemble a better understanding of the world than can be achieved by individuals working in isolation. Communication allows sceptics to assess prior work, repeating the work when warranted. Scientific communication is most reliably achieved by the publication of articles in peer-reviewed journals. It is widely accepted that peer-review helps to ensure that each publication meets community standards of integrity, novelty, conforms to general scientific principles and to the standards and best practices of the relevant scientific domain (

In order to build on prior results, science is best presented in a standardized way. Publications begin with general background that provides context and identifies the most relevant prior work. Methods of experimental setup and data collection are reported in a dedicated block of text that may be referred to as ‘Materials and Methods’ or a similar heading. New information is presented in the “Results’ section, and their significance is discussed in the context of prior work and current understanding in the ‘Discussion’ section. In the ‘Results’, most measurements are given in internationally standardized units, and may be represented in charts and diagrams.

The advent of the Internet has been followed by the emergence of standard formats for digital data. Data standards include the FASTA format for protein and DNA sequence data, IUPAC/IUB codes for referring to amino acids and nucleotides (

The spectrum of biodiversity that manifests in the form of different species is the subject matter of taxonomy. Since the first accepted contributions to taxonomy (

Contributions to taxonomy may take the form of a taxonomic revision, containing treatments of all species in a supraspecific taxonomic group such as a genus or subfamily. Publications may be geographically limited (to a country, region, continent) or be global in scope. Publications may describe one or a small number of new taxa, or add and refine knowledge regarding a taxon that was described previously. Over time, all taxonomic groups receive contributions from multiple researchers working independently. The conventions of scholarship demand that all relevant previous work be cited. Although this is rarely the case in science, taxonomists are especially diligent in this regard and, ideally, are attentive to ALL previous treatments of a taxon (

Taxonomic treatments must be published on paper or in electronic form (

Images as a form of biodiversity data

The identification and diagnostic aspects of taxonomy require researchers to focus on attributes (also known as features, characters, traits or character states) that differ in some way between taxa. The accounts of those attributes are achieved through a combination of text and images (and increasingly other kinds of content). The presentation is explicitly intended to allow comparison with similar organisms, facilitating the task of pointing to or comparing distinguishing features. To achieve this, images typically depict an organism (in whole or selected parts) with a particular orientation and rendered in a particular style to highlight certain details.

Achieving standard approaches

With multiple independent researchers contributing knowledge to a taxonomic group, communities tend to adopt the same views and formats to better communicate with each other. Scientific illustrators are taught to be aware of conventions operating within the scientific discipline to which they are contributing. “Maintaining consistent conventions permits the work of several illustrators to be easily compared and ensures that an illustration will be ‘read’ properly” (

The combination of structured text and standard view images in taxonomic treatments is a mechanism for documenting facts (

Consistency over time

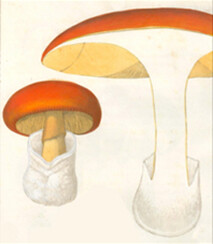

Taxonomy began as a scientific discipline in the middle of the 18th century. Botany and zoology designate different works of Carl Linnaeus as the starting points for their respective taxonomic domains: Species Plantarum (

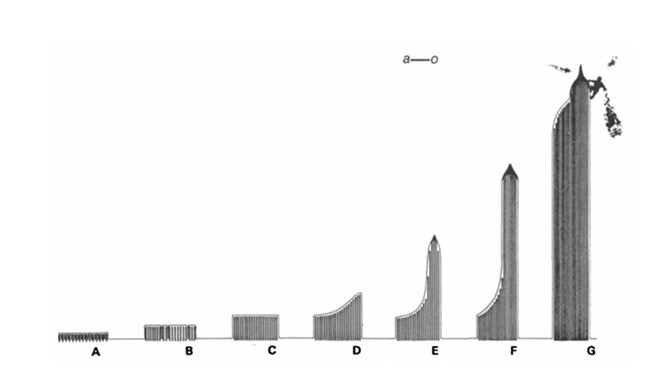

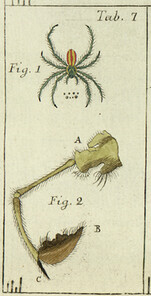

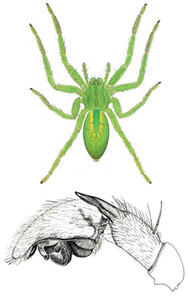

Time series of taxonomic illustrations depicting the spider Micrommata virescens (Arachnida: Araneae: Sparassidae) in standard views.

b: From

Comparative anatomy is a dominant organizing principle in taxonomic publications, regardless of the domain of life concerned. Fig.

Foraminifera are single-celled amoeboid protists, mostly less than 1 mm in length, that typically construct a test (or shell). Although Foraminifera are relatively simple organisms, the cardinal orientations of their anatomy have long been recognized by taxonomists. Fig.

Time series of taxonomic illustrations depicting Sigmoilina (Chromista: Foraminifera: Miliolida: Hauerinidae) in standard views.

b: Sigmoilina sigmoidea, from

c: Sigmoilina species, from

Scientific illustration can be expensive and time consuming to prepare, and costly to publish. This has historically placed limits on how thoroughly a treatment can be illustrated. For example, Biologia Centrali Americana (1879-1915) was a massive effort to document a regional fauna. It comprised 63 weighty volumes and included 1677 figure plates. But only 37% of the species treated were illustrated, and most of those species that were illustrated appeared in only one or two figures (

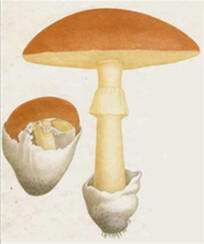

Time series of taxonomic illustrations depicting various katydid (bush crickets) species (Insecta: Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) in standard views.

b: Neoconocephalus affinis, after

Interpretive difficulties arise when images of the same structure are not illustrated in the same way or from the same angle (

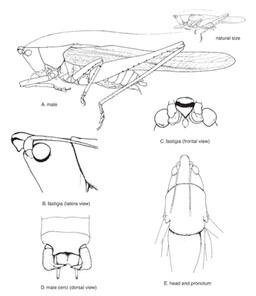

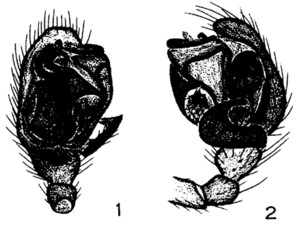

Taxonomic illustrations depicting illustrations of spider (Arachnida: Araneae: Linyphiidae) pedipalps from standard and non-standard views.

b: Illustrations of Bathyphantes gracilis from

c: Illustrations of three Linyphantes species all from the rarely used apical view, from

As taxonomic knowledge within any particular group grows, community consensus about the relative value of various standard view images evolves. The importance of standard views to facilitate comparison has remained unchanged even as technologies and techniques have evolved, facilitating the inclusion of more numerous, high-quality images.

Forms of Images

Taxonomists and scientific illustrators use a variety of media to capture and convey the morphology and anatomy of organisms. Traditional techniques apply ink, graphite, paint, or other such substances alone or in combination to paper, board, or other such surfaces (

Starting around the mid-1980s, new technologies introduced alternative mechanisms for capturing and rendering information about morphology. Computer-aided illustration techniques were developed. Mixed media approaches made it possible to combine multiple techniques into single composite images, such as a body rendered by hand in pencil combined with photographs of wings (Fig.

Use of alternative media to depict and compare anatomy.

b: Scanning electron microscope images comparing the spinnerets of various spider species, from

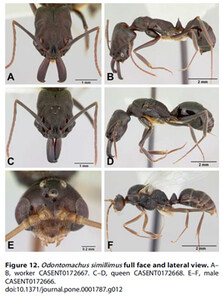

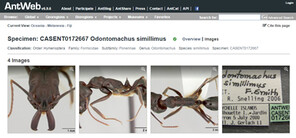

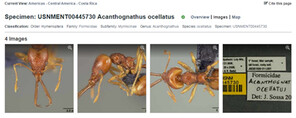

Extended focus composite photographs of ants in a taxonomic publication and the

b: The ant Odontomachus simillimus on

c: The ant Acanthognathus ocellatus on

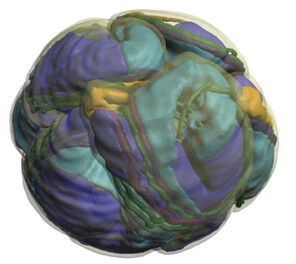

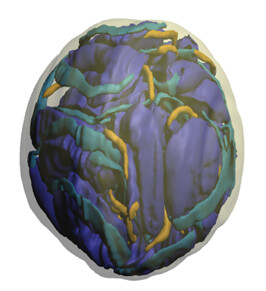

Other radiation imaging techniques, such as X-rays, are used to detail skeletal elements in animals, and tomography (micro-CT, synchrotron) is increasingly used to compare detailed anatomy with the aid of three dimensional computer models (Fig.

Surface renderings of spider sperm reconstructed based on digital tomography.

b: Orsolobus pucara (Orsolobidae), from

Comparative sonograms visualizing sounds made by a selection of animal groups.

b: Oscillograms showing two types of male airborne calls from three species of katydid (Insecta: Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae: Conocephalus), from

c: Three different call types (alarm, threat, and contact) across three monkey species (Mammalia: Primates: Cercopithecidae), from

d: Echolocation calls of three bat species, two of each included to show some intraspecific variation (Mammalia: Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae), from

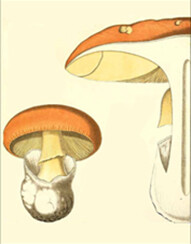

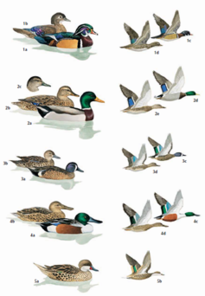

Taxonomic publications often feature photographs from the field, typically depicting living organisms and their habitats (Fig.

Semi-standardized photographs depicting live animals in the field and associated habitats. From

b: The damselfly Africocypha varicolor (Chlorocyphidae), male specimen and type locality.

Various automated methods are increasing used to capture information. Camera traps are automated image capture systems left in the field for an extended time to document wildlife activity in a particular location (

Images of specimens from museum collections.

b: Entire entomological collection drawer imaged using high resolution semi-automated method. Lower image is detail from upper left corner of drawer, from

Of special significance to taxonomists are images of specimens that are held in institutions such as museums and herbaria. These are estimated to be over 3 billion specimens in about 55,000 museums and 3,500 herbaria around the world. Many are of individual organisms that are significant to the taxonomic or nomenclatural history of the taxon. Of these, the most important are the organisms that are type material as they help establish the identity of taxa. All other specimens help to clarify variation within and among species. As taxonomists need to inspect the materials on which nomenclatural and taxonomic decisions are made, they require access to the preserved material. Historically, taxonomists had to visit repositories or have materials shipped to them. This was costly and specimens were at high risk of being damaged if shipped around the world. Now the use of high resolution images inclusive of 3D images is effective for most purposes, cheap and with low risks of damage. This has led to the investment in specimen digitization programs, such as iDigBio is the US (

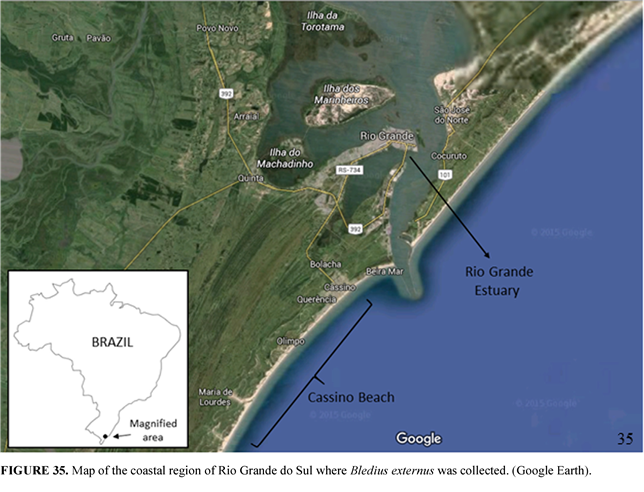

Taxonomic publications often include maps, typically to show the geographic distribution of occurrence records. Base maps may be static, from a printed or graphical source, or rendered as a layer in a GIS (Geographic Information System) environment. Google allows annotation and non-commercial distribution of its maps including their use in journal articles when proper attribution is provided (Fig.

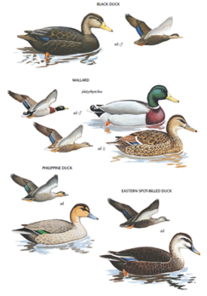

Individual figures are often combined to form plates composed of several species to facilitate comparison (Fig.

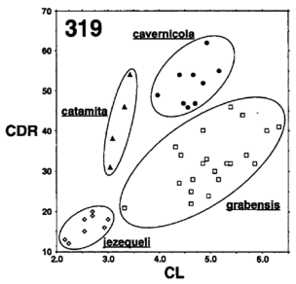

Quantitative data may be represented as scatter plots (with or without trend-lines), graphs, histograms, pie charts, and other such devices. Charts provided for the purpose of establishing or comparing the distinguishing characteristics of a species lack the requisite creative element that makes copyright applicable (Fig.

Visualizations of diagnostic morphometric characters. Quantitative characters, alone or in combination, can contribute to taxonomic identification. Values from an unknown specimen can be compared to those presented in charts such as these.

b: Sculpture ratio, a quantification of shell texture based on a ratio of two measurements, for three Holocene snail species (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Thiaridae: Melanoides), from

To accommodate the growing collection of digitized images relevant to taxonomy, online image archives are growing. These include, Morphbank, BHL on Flikr, and the Biodiversity Literature Repository, which at the time of writing includes over 100,000 images extracted from 15,000 taxonomic publications. Image analysis is being used to automatically identify specimens based on libraries of reference images (

The criteria for determining whether copyright applies to a class of images are the same regardless of subject matter. We emphasize here those classes of images most applicable to taxonomy, but the principle applies to other domains of science. That is, if the image adopts conventions intended to facilitate comparison with other works, then the image is unlikely to be a creative work in the sense of copyright. This does not mean that images in taxonomy are less important than those from creative fields, only that copyright protection is neither applicable legally nor desirable in the context of comparative science.

Rights and scientific images

It is a widespread belief among biologists that scientific images are "owned" by somebody, such as the author, photographer, the institution that employs the creator, or the publishing house responsible for publishing the images (

Imbuing images with a sense of ownership as if they were tangible goods is misleading, because images are not tangible goods (

Numerus clausus of Intellectual Property Rights

National laws specify which non-tangible goods may be regarded as intellectual property. As is the case with property rights with respect to tangible goods, each country may have different rules for intellectual property rights. International instruments such as treaties and conventions aim to harmonize national rules and reduce discrepancies by fixing minimum standards and recommending rules for the application of rights. Various international instruments address specific branches of intellectual property. Well known examples include the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (

The protection of non-tangible goods is always limited to specific areas and specific objects; there is no "general protection". If national laws do not specify that particular non-tangible goods are objects of intellectual property rights, then no rights apply. Individuals cannot claim intellectual property rights over items that are not covered by the relevant national laws.

Intellectual property rights with respect to non-tangible goods is always limited to a restricted number (the so-called "numerus clausus") of specifically attributed rights (

Copyright

Copyright protects certain human creations in art and literature. The minimum standard of this protection, applicable within the 172 countries that have introduced this form of intellectual property rights into their national laws, is defined in the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic works. The Convention was first established in 1886 and has been amended several times (

Article 2 paragraph 1 of the Berne Convention (

Copyright confers to the author a set of privileges which result in far-reaching control over access to the work and over most forms of re-utilization. These rights are limited in time (normally to 50 or 70 years after the author’s death) and may be restricted by numerous legally defined exceptions and limitations. Again, there are important differences from country to country with respect to the content and the extension of rights conferred to authors as well as to the definitions of exceptions and limitations. In the United States of America, the “fair-use-principle” (see below "Exceptions and limitation, fair use") substitutes for the concept of exceptions and limitations.

When a concept or intent is captured in the form of a photograph, graph, drawing or illustration, it is said to be ‘fixed’ or ‘expressed’. The Berne Convention (

The Berne Convention does not define the notion of "work", but leaves that definition to national legislators. As a consequence, the notion of “artistic work” or "photographic work" can vary from country to country. However, there are aspects of this term that are identical in all copyright systems. One of them is that “works” must be man-made. Objects produced by nature or by organisms never qualify as copyrightable. Another important criterion is that intellectual productions qualify as works only if they are somehow original. This criterion does not refer to the content of the work, but to the form of presentation (

The same applies to drawings and other forms of scientific illustrations: they are works in the sense of copyright if they adopt an original form of expression. Illustrations that follow predefined rules or conventions do not qualify as copyrightable works. Illustrations of biological information, especially in taxonomy, usually follow conventions that facilitate comparisons with similar illustrations. When this is the case, the images do not qualify as copyrightable works.

According to U.S. Copyright Law, a work may not qualify for copyright protection if it is about an "idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work." (

The mechanical reproduction of an already existing photograph, drawing, painting or other forms of two-dimensional presentation (such as herbarium sheets) cannot qualify as photographic works for copyright purposes (

Copyright protection, does not only refer to single works, but also to collections of objects (Art. 2 paragraph 5, Berne Convention). Again, the qualification as copyrightable work requires that there is originality and individuality by reason of the selection or the arrangement of the objects. This condition is expressly stated in Art. 10 paragraph 2 of the TRIPs-Agreement (

Database protection

In most countries, databases are protected by intellectual property rights to the extent that they qualify as works in the sense of copyright. This is the case where there is individuality in the selection of data or in the form of presentation of these data. Databases that do not meet these requirements are not subject to specific protection rules.

An important exception to this rule exists in the E.U. The E.U. introduced, with directive 96/9/EC (

The term "database" is defined in Art. 1 no. 2 of directive 96/9/EC: "For the purposes of this Directive, 'database' shall mean a collection of independent works, data or other materials arranged in a systematic or methodical way and individually accessible by electronic or other means." This is consistent with a data environment being structured into one or more tables, of tables having one or more fields, and fields holding data. The fields are defined by metadata. The content of such databases is made visible or can be copied using web-services or web interfaces.

Database protection does not deal with individual data elements. The intellectual property right refers to the database as a whole, not to an individual datum. Database protection may therefore apply to a collection of scientific images, but not to an individual image. The protection is very specific to prevent the extraction and re-utilization of the database as a whole or of substantial parts of it. It does not serve to prevent the extraction and re-utilization of individual data or of groups of datasets that do not constitute a substantial part of a database.

As the European Court of Justice has pointed out in several judgments, European database protection concerns the creation of databases out of material that already exists, but does not deal with the creation of data as such. “Investment in the obtaining, verification or presentation of the contents” refers therefore to the resources and efforts that were called on to find, collect, verify and/or present existing materials. What constitutes a ‘substantial investment’ was explored in case (

Protection against unfair competition

Many countries have legal regulations which seek to prevent unfair competition in industrial and commercial matters. The minimum standard for this protection, applicable in 194 countries, is defined by the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, established in 1883 and amended most recently in 1979 (

1. all acts of such a nature as to create confusion by any means whatever with the establishment, the goods, or the industrial or commercial activities, of a competitor;

2. false allegations in the course of trade of such a nature as to discredit the establishment, the goods, or the industrial or commercial activities, of a competitor;

3. indications or allegations the use of which in the course of trade is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose, or the quantity, of the goods.“

Many countries consider that one form of unfair competition is to reproduce and exploit a competitor’s product or service which is ready for marketing without contributing any novel performance or investment. This legal protection does not aim at a defined intellectual property right, but at lawful commerce. It’s actions prevent behavior that could harm fair competition in an open market.

With respect to scientific images, it might constitute unfair competition to reproduce published images and sell them for individual profit. Unfair competition protection only applies if there is competition between the publisher of the images and the seller. The competition law does not prevent the utilization of published images for other non-competing purposes, such as for any scientific use.

Specific photograph protection in some European countries

A few European countries such as Germany and Austria have introduced special protection for photographs. The purpose is to protect against unfair competition. Photographers in these countries have a specific intellectual property right in their photographic production, but it applies only within that country. The right lasts for 50 years from the date of publication and protects against every form of re-use.

This special protection must be understood in the light of its historical background (

The specific photograph protection applies only to non-individual photographs, taken from three-dimensional objects. As it is the case in copyright law, the reprography of a print, a drawing or a pre-existing photography is not a photograph in the sense of these laws (

Discussion

Considering this outline of intellectual property rights, we conclude that principles of copyright do not normally apply to scientific images because most images adhere to the conventions of the discipline. Certainly, copyright is not applicable to images that are intended to facilitate comparison among related taxa.

Rights in scientific images apply only in special cases

Copyrightable works are defined as individual, original human creations, that show originality in the form of presentation compared to other works of the same kind. Most scientific images lack an original form of expression and so cannot qualify as copyrightable works. This is particularly true for machine-generated images, such as robotic systems used to digitize specimens in natural history collections, or pictures obtained from camera-traps positioned to monitor animal activity over time. Such pictures are not man-made and they can consequently not be copyrightable works. For the same reason, they do not qualify for the special photograph protection that applies within a few European countries.

Individually prepared photos and drawings, produced in line with scientifically recognized and standardized conventions, also fall outside the scope of copyright because of their standardized form of expression (

Similar arguments apply to the combination of text and standardized images that make up taxonomic treatments. Treatments follow conventions to facilitate the effective documentation of facts, and comparison between descriptions. The expectations are so firm that peer review would not allow treatments that are individual in the sense of literature or art. They are technically “correct” if they are done according to the applicable protocols, and they are “incorrect” if they do not follow those standards. They express facts in a pre-established, standardized form. They do not, therefore, qualify as copyrightable works (

The same criterion leads to the conclusion that collections of biodiversity data are also not copyrightable by default as the selection and arrangements of those collections as well as their form of expression follow predefined systems of biological classification, metadata, ontology, vocabulary and quantitative units. Tables of quantitative or qualitative information can be considered as collections of data, the selection and presentation of which are scientifically predefined. The more complete and systematic a collection, the less probable it is that it qualifies as a work in the sense of copyright. This conclusion does not devalue scientific work, but it is a logical consequence of copyright legislation that aims to protect individual forms of expression.

The situation is less consistent as far as wildlife illustrations are concerned. Some images are created for artistic purpose or to create a commercial product. Some photographs or drawings generated during field research and which are not produced in line with established standards, may fulfil the criterion of individuality and originality and therefore qualify as works in the sense of copyright. Copyright protection may apply to such images.

The situation may also be slightly different in E.U. countries which apply the sui generis protection for databases. Collections of biodiversity data may be subject to this specific protection against the re-use of a substantial part or the totality of the content of the database. Another exception that researchers should be aware of is the specific photograph protection in some European countries (such as Austria, Denmark, Germany, and Italy). Of course, these specific protection rules apply only in the countries that have introduced them. Outside these countries, the protection has no legal effect.

Blue2 - an updated “Blue List”

‘The blue lists’ identify those elements which may reasonably be expected to occur in taxonomic works and, because of their compliance with conventions, lack the creativity that makes copyright applicable. The first list (

- A hierarchical organization (= classification), in which, as examples, species are nested in genera, genera in families, families in orders, and so on.

- Alphabetical, chronological, phylogenetic, palaeontological, geographical, ecological, host-based, or feature-based (e.g. life-form) ordering of taxa.

- Scientific names of genera or other uninomial taxa, species epithets of species names, binomial combinations as species names, or names of infraspecific taxa; with or without the author of the name and the date when it was first introduced. An analysis and/or reasoning as to the nomenclatural and taxonomic status of the name is a familiar component of a treatment.

- Information about the etymology of the name; statements as to the correct, alternate or erroneous spellings; reference or citation to the literature where the name was introduced or changed.

- Rank, composition and/or apomorphy of taxon.

- For species and subordinate taxa that have been placed in different genera, the author (with or without date) of the basionym of the name or the author (with or without date) of the combination or replacement name.

- Lists of synonyms and/or chresonyms or concepts, including analyses and/or reasoning as to the status or validity of each.

- Citations of publications that include taxonomic and nomenclatural acts, including typifications.

- Reference to the type species of a genus or to other type taxa.

- References to type material, including current or previous location of type material, collection name or abbreviation thereof, specimen codes, and status of type.

- Data about materials examined.

- References to image(s) or other media with information about the taxon.

- Information on overall distribution and ecology, perhaps with a map.

- Known uses, common names, and conservation status (including Red List status recommendation).

- Description and / or circumscription of the taxon (features or traits together with the applicable values), diagnostic characters of taxon, possibly with the means (such as a key) by which the taxon can be distinguished from relatives.

- General information including but not limited to: taxonomic history, morphology and anatomy, reproductive biology, ecology and habitat, biogeography, conservation status, systematic position and phylogenetic relationships of and within the taxon, and references to relevant literature.

- Photographs (or other image or series of images) by a person or persons using a recording device such as a scanner or camera, whether or not associated with light- or electron-microscopes, using X-rays, acoustics, tomography, electromagnetic resonance or other electromagnetic sources, of whole organisms, groups, colonies, life stages especially from dorsal, lateral, anterior, posterior, apical or other widely used perspectives and designed to show overall aspect of organism.

- Photographs (or other image or series of images) by a person or persons using a recording device such as a camera associated with light- or electron-microscopes, using X-rays, acoustics, tomography, electromagnetic resonance images or other electromagnetic sources) of parts of organisms such as but not limited to appendages, mouthparts, anatomical features, ultrastructural features, flowers, fruiting bodies, foliage, intra-organismic and inter-organismic connections, of compounds and analyses of compounds extracted from organisms that demonstrate the characteristics of an individual or taxon and/or allow comparison among individuals/taxa.

- Photographs (or other image or series of images) of whole organisms, groups, colonies, life stages, parts of organisms made by camera or scanner or comparable devices using automated procedures.

- Drawings of organisms or parts of organisms made by a person or persons to demonstrate the characteristics of an individual / taxon or to allow comparisons among taxa.

- Graphical / diagrammatic representation (such as, but not limited to, scatter plots with or without trend lines, histograms, or pie charts) of quantifiable features of one or more individuals or taxa for the purposes of showing the characteristics of or allowing comparison of individuals or taxa and made by a person or persons.

The first ‘Blue List’ (

The situation may differ as far as wildlife illustrations and photos produced during field research are concerned. Such illustrations may be expressed in an individual form and so qualify as works to which copyright may be applied.

Exceptions and limitations, fair use

Images that do not qualify as copyrightable work and that are not protected by any other intellectual property right, can be reused by any other person for any other legal purpose. Images and collections of images that are protected by copyright or by database protection may only be used with the consent of and under terms set by the rights holder. However, there are situations where even the use of copyrighted material is allowed without authorization.

The rules for these copyright exceptions vary fundamentally in different law systems. While the U.S. applies the so called “fair-use-defense”, European countries aim at the same objective through a catalogue of legally binding rules, called “exceptions and limitations”. In the U.K. and other common-law legislations, the exceptions and limitations are sometimes combined with a “fair-dealing-clause”. The different systems lead to different consequences with respect of the use of copyrighted material.

The “fair-use-clause” is part of the U.S. Copyright Act (

The “exceptions and limitations” which are used in the great majority of copyright laws are specific legal rules that authorize uses of copyrighted material for certain purposes. A commonly allowed exception to Copyright law is the use of copyrighted material for research purposes. These rules can be found in the national copyright laws and vary from country to country. The E.U. Directive 2001/29/EC (

The re-use of copyrighted material even for research purposes may therefore be hampered by current copyright and database protection. The risk is particularly true for international big data studies that were not foreseen by the law-makers and do not fit into the “fair-use”-criteria of U.S. copyright nor will be authorized by any exception rule of European copyright law. Such large projects are likely to inadvertently run counter to some exceptions and limitations or legislation that applies in some national jurisdictions (

No economic incentive

In creative fields, copyright is sometimes justified as a mechanism for encouraging innovation and creativity (

Because taxonomic research is funded in great part by public and philanthropic sources rather than capital investment, it follows that the fruits of this investment and labor are owed to the public rather than to investors. The current practice to cede legal rights to a private publisher, who may use these rights to restrict access to such publications, is highly problematic. The interests of both science and the public are better served by investing in publishing models that maximize accessibility, rather than producing research products paid for by, but not accessible to, the public (

Law and opinions

We do not present our opinion as an indisputable interpretation of the Law, but that it is one of several competing opinions. Laws are not rigid structures but are subject to interpretation. Judicial consensus as to how a law should be interpreted emerges through 'case law' - a success of cases in which the application of the law is contested. We know of no case history that specifically deals with the application of copyright law to biodiversity images.

Competing opinions are held by publishers and by scientists. Until relatively recently, publishers presented themselves as allies of and advocates for scientists, promoting dissemination and awareness of scientific content and further served the scientific community by taking on board the responsibility for shielding scientists from queries about re-use of their materials. In return, they received income from publication fees, sale of publications, and publicity for themselves. Increasingly, the balance has shifted to the commercial model for re-use of scientific literature. This included monopolizing access to their products by, in some cases, seeking transfer of rights from authors to publishers. Authors are put under pressure to assign rights to the publisher to protect the financial interests of the publishers. This has led to a backlash that created many new and exciting new publishing models (

The historical practices of publishers have established a largely untested opinion as to rights in regard to scientific data, scientific data objects, and publications. Scientists as authors are familiar with this model, some accept it others do not.

Several further arguments have developed from the reliance of scientists on information generated by others. One is the presumption that it is legitimate and reasonable to re-use this information but with the ethical obligation to give credit to those who generated the data. That is, a corner-stone of science is that information is free and openly available.

Another is that research funded through the public purse (as most is) should find its place in the public domain. Taxonomic research is funded in great part by public and philanthropic sources rather than by capital investment. The opinion that the fruits of investment and labor are owed to the public rather than to investors lead to a conclusion that the practice of ceding legal rights to private publishers, who may use these rights to restrict access to such publications, is ethically unsound. Science and the public are better served by investing in publishing models that maximize accessibility, rather than producing research products paid for by, but not accessible to, the public (

A final opinion is the value of subjecting reports to scrutiny. This process can correct errors, show weaknesses in arguments, point to other publications that are not cited. That is, scrutiny adds value. The traditional publishing model adds independent scrutiny by two or three reviewers of manuscripts. Other models that make content freely accessible, even before publishing, provide increased opportunity for independent checks and leads to a healthier and more robust science. The malleable nature of scientific products further undermines any case that copyright principles to apply to scientific content.

The value of the competing opinions regarding copyright law as it applies to images in the biological sciences has not been tested in Court. There is as yet no judicial consensus. We argue that the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co. (

Attribution

The principles of scholarship in taxonomic research include the expectation that relevant previous work be cited. Citation of publications identifies prior work and helps to assure reproducibility and comparability of the results of scientific research.

Citation offers a mechanism of providing credit to work by others, that is, attribution. In an increasingly digital world, we should be attentive to the principles of citation, comply with any legal obligations, and identify those who acquired the data or in any way contributed to the supply chain and/or added value to data (

Attribution in copyright

In the case of copyrighted work, citation is a legal obligation. As is stipulated in Art. 6bis of the Berne Convention (

A special clause of the Berne Convention (Art. 10) deals with “quotations”. Quotations from a work made lawfully available to the public are permissible as long as the extent of the quotation does not exceed that justified by its purpose. Every quotation must be attributed to the source, and has to mention the name of the author if it appears in this source. This obligation is also transformed into the national law of nearly all member states of the Berne Convention and is therefore of general validity.

These legal obligations, however, apply only to copyrighted works or to quotations from copyrighted works. As we have seen before, scientific images are in most cases not copyrightable. As a consequence, there is no general obligation to attribute scientific images based in copyright law. Legal obligations are limited to the minority of cases where scientific images are copyrightable.

The E.U. database protection as well as the protection against unfair competition do not include any obligation to attribution. The same is true for the protection of non-copyrightable photographs as it exists in some European country. The only legal instrument that contains an obligation to attribute is therefore the copyright law.

Despite the absence of legal obligations, the tradition of citation has served science well, and benefits both the cited with credit and the citer with a reputation for integrity. It is the view of the authors that failing to recognize authors and/or suppliers of images is comparable to plagiarism. As noted by

How to attribute authorship in images

In the previous sections, we have laid out the arguments as to why images in scientific articles should be considered to be data, and not encumbered by copyright. We also argue that all previous work should be given attribution. Acceptance by the community that most images are not being subject to copyright must be accompanied attribution. It will be up to the scientific community to develop attribution standards.

In order to make recommendations about how to give attribution to the original authors, we take inspiration from a few other sources that have thought deeply about this subject, namely, the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), Harvard University Library, and Europeana.

The data use policy of the DPLA is based on goodwill, not a legal contract (

Europeana, the digital portal for all of Europe’s culture, has a mission to “transform the world with culture!” As such, Europeana makes all metadata available on europeana.eu free of restrictions, under the terms of the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.” Europeana does encourage users to “follow the Europeana Usage Guidelines for Metadata and to provide attribution to the data sources whenever possible”.

Following in the footsteps of DPLA, Harvard Library, Europeana, and others, we recommend that authors recognize the author and source for each image that is used, and that publishers assign a DOI or other unique identifier to every image and mark the images with CC0. Publishers should provide a clear statement about copyright, recommend a suggested citation for images in the Terms of Use and the Data Policy sections of the website. Elsewhere we have argued that the use of unique identifiers with each data item (image in this case) allows the application of annotation technology that is capable of rewarding all members of the supply chain with credit and quantifiable metrics (

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Tim Smith (Zenodo, CERN), Lyubo Penev (Pensoft), Scott Miller (Smithsonian Institution), Chuck Miller (Missouri Botanical Garden) and Alberto Ballerio for advice and discussion, and to the numerous colleagues we involved and challenged with this view over the last years in any conference, meeting, or gathering we attended. Thanks to PLoS Biology for reviewing an earlier draft of the manuscript and, despite its rejection, whose reviews have beein incorporated and addressed here and led to a more complete article. Thanks to all the many commentators on the preprint (http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2016/11/11/087015) uploaded to the bioRxiv preprint service, exposed by 56 unique followers to a potential of over 100,000 followers whose concerns we tried to address and helped improve the manuscript.

Funding program

EU BON project, funded by European Union’s Seventh Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement No 308454. DJP was supported by the US National Science Foundation grant DBI-1062387 (The Global Names Architecture, an infrastructure for unifying taxonomic databases and services for managers of biological information).

Author contributions

WE, DA, PK, DJP, and JM conceptualized the study. WE performed the legal analysis. DA provided administrative responsibility. WE and JM wrote the initial draft with substantial input from DA, PK, and DP. All authors contributed to the final draft.

References

- Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach.BMC Research Notes2(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-2-53

- AntWeb. http://www.antweb.org. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Forderung aus Urheberrechtsverletzung / unerlaubte Handlung. Release date:2016-6-01. URL: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.322761

- A Revision of the Malagasy Species of Homalium Sect. Eumyriantheia Warb. (Salicaceae).Candollea71(1):33‑60. https://doi.org/10.15553/c2016v711a7

- Promoting Access to Public Research Data for Scientific, Economic, and Social Development.Data Science Journal3:135‑152. https://doi.org/10.2481/dsj.3.135

- From GATT to TRIPs- The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.Wiley,504pp.

- Collezione dei funghi commestibili, velenosi e malsani della provincia di Mantova : con figure lavorate a colori.Tipografia Virgiliana,Mantova [Italy],126pp.

- No specimen left behind: industrial scale digitization of natural history collections.ZooKeys209:133‑146. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.209.3178

- Comparison of morphometric techniques for shapes with few homologous landmarks based on machine-learning approaches to biological discrimination.Paleobiology36(3):497‑515. https://doi.org/10.1666/08068.1

- Social complexity parallels vocal complexity: a comparison of three non-human primate species.Frontiers in Psychology4https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00390

- Report on the Foraminifera collected by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-1876.Report of the scientific results of the voyage of HMS Challenger during the years 1873-76 under the command of Captain George S Nares and Captain Frank Tourle Thomson. Zoology.Vol IX.Neill,Edinburgh.

- Birds of East Asia. Helm Field Guides.Christopher Helm,London,528pp.

- The Herbarium Handbook.3rd Edition.Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew,334pp.

- An Illustrated Flora of the Northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions from Newfoundland to the parallel of the southern boundary of Virginia, and from the Atlantic Ocean westward to the 102d meridian.2nd Edition,Vol. 2.Scribner's Sons,New York,735pp. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.55504

- Advanced Techniques for Imaging Parasitic Hymenoptera (Insecta).American Entomologist51(1):50‑56. https://doi.org/10.1093/ae/51.1.50

- Herbier de la France, ou collection complette des plantes indigenes de ce royaume; Avec leurs Détails Anatomiques, leurs propriétés, et leurs usages en Medecine.Volume 3.Published by the author (Rue des Postes, au coin de celle du Cheval vert) and Diderot,Paris.

- Update on the Brazilian coastal species of Bledius Leach (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae: Oxytelinae) with the description of two new species.Zootaxa4111(2):145‑57. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4111.2.3

- TaxPub: An Extension of the NLM/NCBI Journal Publishing DTD for Taxonomic Descriptions.Proceedings 2010.National Center for Biotechnology Information (US),Bethesda. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47081/

- A Hundred New Species of American Spiders.Bulletin of the University of Utah32(13):1‑117. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/36.2.318

- Scanning electron microscopy in taxonomy and functional morphology.Clarendon for the Systematics Association,Oxford,315pp.

- Svenska Spindlar uti sina hufvud-slågter indelte samt under några och sextio särskildte arter beskrefne och med illuminerade figurer uplyste / Aranei Svecici, descriptionibus et figuris æneis illustrati, ad genera subalterna redacti, speciebus ultra LX determinati.Salvius,Stockholm,154pp. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.119890

- Spinneret silk spigot morphology: evidence for the monophyly of orbweaving spiders, Cyrtophorinae (Araneidae), and the group Theridiidae plus Nesticidae.Journal of Arachnology17:71‑95.

- A revision of the funnelweb mygalomorph spider subfamily Ischnothelinae (Araneae, Dipluridae).Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History226:1‑133.

- A Monograph of the Foraminifera of the North Pacific Ocean. Part VI. Miliolidae.Bulletin United States National Museum71:vii‑108. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.03629236.71.6

- DPLA Data Use Best Practices. https://dp.la/info/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/DPLADataUseBestPractices.pdf. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Sixty new dragonfly and damselfly species from Africa (Odonata).Odonatologica44:447‑678. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.35388

- Autoren und Apparate: Die Geschichte des Copyrights im Medienwandel.S. Fischer Verlag GmbH,Frankfurt a. M.,432pp.

- Flow cytometry as a tool for the study of phytoplankton.Scientia Marina64(2):135‑156. https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.2000.64n2135

- Sexual Selection and Animal Genitalia.Harvard University Press,Cambridge,244pp.

- Open exchange of scientific knowledge and European copyright: The case of biodiversity information.ZooKeys414:109‑135. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.414.7717

- Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1469793705452&uri=CELEX:32001L0029. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Micro-computed tomography: Introducing new dimensions to taxonomy.ZooKeys263:1‑45. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.263.4261

- A Revision of Malagasy Species of Anochetus Mayr and Odontomachus Latreille (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).PLoS ONE3(5):e1787. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001787

- Changing Incentives to Publish.Science333(6043):702‑703. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1197286

- Acoustic Identification of Eight Species of Bat (Mammalia: Chiroptera) Inhabiting Forests of Southern Hokkaido, Japan: Potential for Conservation Monitoring.Zoological Science21(9):947‑955. https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.21.947

- Scientific Method in Practice.Cambridge University Press,Cambridge,435pp. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511815034

- Camera-trapping: a new tool for the study of elusive rain forest animals.Tropical Biodiversity1(2):131‑135.

- Harvard Library Open Metadata. http://library.harvard.edu/open-metadata

- Developing integrated workflows for the digitisation of herbarium specimens using a modular and scalable approach.ZooKeys209:93‑102. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.209.3121

- Digital Imagingof Biological Type Specimens. A Manual of Best Practice.Results from a study of theEuropean Network for Biodiversity Information,Stuttgart,viii+309pp. URL: http://www.gbif.org/system/files_force/gbif_resource/resource-80576/enbi_ImagingBiologicalSpecimens_manual_en_v1.pdf?download=1

- Der Schutz der Fotografie im Urheberrecht Deutschlands, Frankreichs und der Vereinigten Staaten.C.H.Beck,München,274pp.

- Systematics as Cyberscience.MIT Press,Cambridge,x+307pp. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262083713.001.0001

- The Guild Handbook of Scientific Illustration.Second Edition.John Wiley & Sons,Hoboken,656pp.

- Whole-drawer imaging of entomological collections: benefits, limitations and alternative applications.Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies12(1):1‑13. https://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1021218

- C-203/02 - The British Horseracing Board and Others. http://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?language=en&jur=C,T,F&num=C-203/02&td=ALL. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Amendment of Articles 8, 9, 10, 21 and 78 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature to expand and refine methods of publication.ZooKeys219:1‑10. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.219.3944

- IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. Abbreviations and symbols for the description of the conformation of polypeptide chains. Tentative rules (1969).Biochemistry9(18):3471‑3479. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00820a001

- North American spiders of the genus Bathyphantes (Araneae, Linyphiidae).American Museum Novitates2364:1‑70.

- Estimating tiger Panthera tigris populations from camera-trap data using capture—recapture models.Biological Conservation71(3):333‑338. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(94)00057-w

- Changes to publication requirements made at the XVIII International Botanical Congress in Melbourne - what does e-publication mean for you?Brittonia63(4):505‑509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12228-011-9205-1

- DeepSurveyCam—A Deep Ocean Optical Mapping System.Sensors16(2):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/s16020164

- Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti.Princeton University Press,Princeton,384pp.

- A guide to the practice of herbarium taxonomy.Regnum Vegetabile, Volume 58.International Bureau for Plant Taxonomy and Nomenclature of the International Association for Plant Taxonomy,Utrecht,60pp.

- 17 U.S. Code § 107 - Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/107. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- 17 U.S. Code § 102 - Subject matter of copyright: In general. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/102. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340. https://www.law.cornell.edu/copyright/cases/499_US_340.htm. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Species Plantarum (2 Volumes).Salvius,Stockholm,xii+1231pp. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.669

- Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis.Laurentius Salvius,Stockholm,854pp. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.542

- Philosophia botanica: in qua explicantur fundamenta botanica cum definitionibus partium, exemplis terminorum, observationibus rariorum, adjectis figuris aeneis.Second Edition.Thomae,Vienna,360pp. https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-22522

- Ultrastructure of spermatozoa of Orsolobidae (Haplogynae, Araneae) with implications on the evolution of sperm transfer forms in Dysderoidea.Journal of Morphology275(11):1238‑1257. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.20332

- Traité de la propriété littéraire et artistique.Litec,Paris,xxi+1104pp.

- The Mythology of the Public Domain: Exploring the Myths Behind Attacks on the Duration of Copyright Protection.Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review (Loyola Law Review)36:253‑322.

- Atlas des plantes de France: Utiles, Nuisibles et Ornementales.Librairie des Sciences Naturelles,Paris.

- Guide de la Convention de Berne pour la protection des oeuvres littéraires et artistiques.World Intellectual Property Organization,Genève,258pp.

- Managing the Modern Herbarium, An Interdisciplinary Approach.Society of the Preservation of Natural History Collections and The Royal Ontario Museum Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Research,Washington D.C.,384pp.

- Evolutionary morphology of the male reproductive system, spermatozoa and seminal fluid of spiders (Araneae, Arachnida) – Current knowledge and future directions.Arthropod Structure & Development43(4):291‑322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asd.2014.05.005

- A camera trap assessment of terrestrial vertebrates in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda.African Journal of Ecology51(1):21‑31. https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.12004

- Vermivm terrestrium et fluviatilium, seu animalium infusoriorum, helminthicorum et testaceorum, non marinorum, succincta historia.Heineck and Faber,Copenhagen and Leipzig,xxvi+214pp. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.12733

- Katydids of Costa Rica: Vol. 1. Systematics and bioacoustics of the cone-head katydids (Orthopters: Tettigoniidae: Conocephalinae sensu lato).The Orthopterists' Society,164pp. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.270035

- Five task clusters that enable efficient and effective digitization of biological collections.ZooKeys209:19‑45. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.209.3135

- Urheberschutz für Software-Produktbeschreibungen in Zeitschriftenartikeln. http://www.jurpc.de/jurpc/show?id=20020231. Accessed on: 2002-6-25.

- Camera traps in ecology: methods and analyses.Springer,Tokyo,xiv+271pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-99495-4

- Shared Values and Membership Principles of the OCLC Cooperative. http://www.oclc.org/content/dam/oclc/membership/values_principles.pdf. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- BioNames: linking taxonomy, texts, and trees.PeerJ1:e190. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.190

- Names are key to the big new biology.Trends in Ecology & Evolution25(12):686‑691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.09.004

- Scientific names of organisms: attribution, rights, and licensing.BMC Research Notes7(1):79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-79

- Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America.Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,New York,544pp.

- Descriptions of New or Inadequately Known American Spiders (Second Paper).Annals of the Entomological Society of America22(3):511‑525. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/22.3.511

- The genus Sigmoilina Schlumberger.Australian Journal of Zoology22(1):105‑115. https://doi.org/10.1071/zo9740105

- The morphology and relationships of the walking mud spiders of the genus Cryptothele (Araneae: Zodariidae).Zoologischer Anzeiger - A Journal of Comparative Zoology253(5):382‑393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcz.2014.03.002

- Linking of digital images to phylogenetic data matrices using a morphological ontology.Systematic Biology56(2):283‑294. https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150701313848

- The WIPO Treaties 1996.Butterworths Lexis Nexis,London,581pp.

- Digital Imaging of beetles (Coleoptera) and other three-dimensional insects.Digital imaging of biological type specimens: a manual of best practice.European Network of Biodiversity Information: 41-55,Stuttgart.

- One hundred and one new species of Trigonopterus weevils from New Guinea.ZooKeys280:1‑150. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.280.3906

- The Spiders of Great Britain and Ireland [3 Volumes].Harley Books,Colchester,229+204+256pp.

- A new species and new records of Cryptodacus (Diptera: Tephritidae) from Colombia, Bolivia and Peru.Zootaxa4111(3):276‑290. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4111.3.5

- Histoire Des Champignons Comestibles Et Vénéneux.Deuxième édition.Fortin, Maset et Cie,Paris,482pp. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.114851

- A reference process for automating bee species identification based on wing images and digital image processing.Ecological Informatics24:248‑260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2013.12.001

- Insecta. Orthoptera, Volume I.Biologia Centrali-Americana.R.H. Porter,London. URL: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/14636#page/1/mode/1up

- Collecting and preserving insects and mites: techniques and tools.Systematic Entomology Laboratory, USDA,Washington, D.C.,68pp. URL: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80420580/CollectingandPreservingInsectsandMites/collpres.pdf

- Urheberrecht. Kommentar.4 Auflage.C.H. Beck,München.

- The outflow of academic papers from China: why is it happening and can it be stemmed?Learned Publishing24:95‑97. https://doi.org/10.1087/20110203

- Overestimation of heterotrophic bacteria in the Sargasso Sea: direct evidence by flow and imaging cytometry.Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers42(8):1399‑1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0967-0637(95)00055-b

- Camera trap, line transect census and track surveys: a comparative evaluation.Biological Conservation114(3):351‑355. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3207(03)00063-6

- Beyond dead trees: integrating the scientific process in the Biodiversity Data Journal.Biodiversity Data Journal1:e995. https://doi.org/10.3897/bdj.1.e995

- Comparison of phylogenetic signal between male genitalia and non-genital characters in insect systematics.Cladistics26(1):23‑35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-0031.2009.00273.x

- The Role of the Scanning Electron Microscope in Plant Anatomy.Kew Bulletin28(1):105‑115. https://doi.org/10.2307/4117068

- no. 130 III 714. Auszug aus dem Urteil der I. Zivilabteilung i.S. Blau Guggenheim gegen British Broadcasting Corporation BBC (Berufung). http://relevancy.bger.ch/php/clir/http/index.php?lang=de&type=show_document&highlight_docid=atf://130-III-714:de. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- no. 134 III 166. Auszug aus dem Urteil der I. zivilrechtlichen Abteilung i.S. Documed AG gegen A. und ywesee GmbH (Beschwerde in Zivilsachen). http://relevancy.bger.ch/php/clir/http/index.php?lang=de&type=show_document&highlight_docid=atf://134-III-166:de. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Development of macrociliary cells in Beroë. II. Formation of macrocilia.Journal of cell science89 (Pt 1):81‑95.

- Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council.Official Journal of the European CommunitiesL(77):20‑28. URL: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31996L0009&rid=1

- Evolution of leaf warbler songs (Aves: Phylloscopidae).Ecology and Evolution5(3):781‑798. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1400

- Ist der immaterialgüterrechtliche “numerus clausus” gerecht?Festgabe für M. Gutzwiller.Helbing & Lichtenhahn,Basel,769-787pp.

- Legal Interoperability of Research Data: Principles and Implementation Guideline.RDA-CODATA Legal Interoperability Interest Group,42pp. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.162241

- Parnassia palustris, Spiterstulen, Jotunheimen, Norway. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parnassia_palustris_ellywa.png. Accessed on: 2016-9-29.

- Thinking About Biology.Cambridge University Press,Cambridge,248pp. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511754975

- Darwin Core: An Evolving Community-Developed Biodiversity Data Standard.PLoS ONE7(1):e29715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029715

- Describing Species: Practical Taxonomic Procedure for Biologists.Columbia University Press,New York,518pp.

- WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT). http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/wct/. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Rome Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organizations. http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details.jsp?id=12656. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (as amended on September 28, 1979). http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details.jsp?id=12633. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (as amended on September 28, 1979). http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details.jsp?id=12214. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization. Annex 1C: Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/legal_e.htm#TRIPs. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights. https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips_01_e.htm. Accessed on: 2017-2-22.

- World Register of Marine Species at VLIZ. http://www.marinespecies.org. Accessed on: 2016-8-19.

Supplementary materials

Kukulcania hibernalis (Filistatidae), from Michalik and Ramírez (2014), with credit to E. Lipke. This PDF file contains interactive 3D content. Click on the image to activate content and use the mouse to rotate objects. Additional functions are available through the menu in the activated figure.

Orsolobus pucara (Orsolobidae), from Lipke et al. (2014). This PDF file contains interactive 3D content. Click on the image to activate content and use the mouse to rotate objects. Additional functions are available through the menu in the activated figure.