|

Research Ideas and Outcomes : Research Idea

|

|

Corresponding author: Megha Abbey (abbey1me@gmail.com)

Received: 21 Sep 2016 | Published: 28 Sep 2016

© 2016 Megha Abbey.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: Abbey M (2016) Functional characterization of the several splice variants of Fmr1. Research Ideas and Outcomes 2: e10593. doi: 10.3897/rio.2.e10593

|

|

Abstract

Background

Fmr1 has been known to be a crucial contributor in neurodevelopment. Events such as alternative splicing in its coding region and the use of different trancription start and end sites in its non-coding regions result in the production of a range of mRNA transcripts. Structural and functional characterization of some of these transcripts have been performed, but several of them remain uncharacterized. Differences in the temporal and spatial expession of these transcripts may play important roles in regulating the development of the fetal and adult brain structures and thus, their physiological functions.

New information

The extensive set of experiments suggested in this study plan exploit mice brain, neuronal cultures and in vitro studies. The proposed study for the identification and full characterization of the known and novel transcripts of Fmr1 is an important initial step towards the assignment of the specific known roles and the determination of the so-far unknown roles of Fmr1 at the various stages of neurodevelopment. This systematic study helps in categorizing the transcripts that can produce stable proteins and further understand their cellular localization and cellular functions individually and in concert with each other. Similarly, identification of the non-coding transcripts helps us in exploring their roles in the regulatory processes, if any, which might also impact the expression of the coding transcripts in the neuronal cells.

Keywords

FMRP, Fmr1, splice variant, alternative splicing, CGG repeats, protein isoform

Overview and background

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that results in intellectual disabilities in addition to autistic traits, anxiety and seizures. It is caused by the dysfunctioning of Fmr1 (fragile X mental retardation gene 1) located on the X-chromosome. Fmr1 is also identified as a monogenic cause of autism. It encompasses ~38 Kb and consists of 17 exons. Its 5’ UTR consists of CGG repeats. In FXS, the number of CGG repeats increases to >200 (full mutation) instead of the healthy number of <55. This increase leads to transcriptional silencing of Fmr1 and thus, a complete loss of expression of its encoded protein, FMRP. In addition, if the CGG repeat number increases to be within 55-200 (pre-mutation), Fmr1 RNA levels increase in the cells, though FMRP levels are reduced. This condition is linked to two disorders, namely, fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome and fragile X-related primary ovarian insufficiency. Studies conducted with Fmr1 KO models have shown that loss of Fmr1 is associated with an increased density of immature dendritic spines in the neuronal cells. Though, several recent studies have suggested that this phenotype varies with respect to the different brain areas and the different developmental stages of the brain (as reviewed in

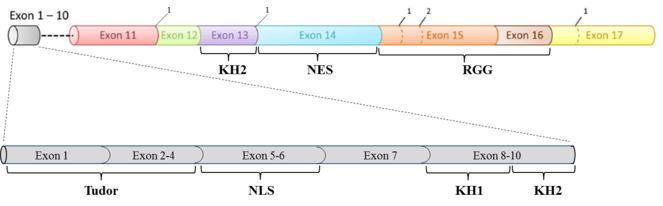

FMRP consists of two Tudor domains, a nuclear localization signal (NLS), three K homology domains (KH0, KH1, KH2), a nuclear export signal (NES) and an arginine-glycine-glycine domain (RGG) from N- to C-terminus. The tudor, KH and RGG domains are mainly involved in RNA binding, though they also have protein interaction partners. FMRP is ubiquitous but is highly expressed in the brain and reproductive organs. Being a RNA-binding protein, FMRP has been shown to be involved in the regulation of translation, stability and localization of several mRNA targets (as reviewed in

Diagrammatic representation of the exon structure of Fmr1 and its corresponding functional domains. The splice acceptor sites are marked as 1 and 2.

As per some recent studies, it has been shown that different transcription start and end sites exist and are used during the transcription of mouse and human Fmr1, which along with the alternative splicing events occurring in the coding region, would account for a diverse range of transcripts and thus, would regulate the production of different protein isoforms of Fmr1 (

Objectives

As stated above, in order to fully dissect the role of Fmr1 in the functioning of a healthy brain, it is important to draw a map of the wide variety of transcripts (coding and non-coding) produced by the gene in the different regions of the brain at different stages during development. This detailed information would form the basis of a systematic analysis and finding correlations between the existence/expression of Fmr1 and the different on-going processes in the brain. For such an analysis, it is crucial to identify and functionally characterize all the known and novel transcripts of Fmr1. Henceforth, this task is largely divided into three objectives: (a) identification, cloning and characterization of the various (known and novel) splice variants of Fmr1 expressed in the different regions of the mouse brain, (b) analysis of the known Fmr1 transcripts and isoforms and (c) elucidating the structure of full-length FMRP.

Implementation

I. Identification, cloning and characterization of the various (known and novel) splice variants of Fmr1 expressed in the different regions of the mouse brain

a. Cloning and sequencing of the splice variants: Pretto et al. in their study have predicted the presence of 24 different transcripts of Fmr1 as a result of alternative splicing in the coding region (Pretto et al. 2014). They along with other studies have validated the presence of different Fmr1 splice variants in the different regions of the mouse brain at different developmental stages ranging from the embryo to adult (

b. Protein expression from the splice variants as a result of variations in coding and non-coding regions: Since, it would be important to know if the splice variants of Fmr1 are translated/are capable to produce stable proteins in the cells, protein expression from each of these different transcripts could be monitored. (i) If appropriate antibodies would be available at the time, this could be done using Western blotting, or (ii) a fusion tag sequence could be inserted immediately upstream of the mRNA coding sequence and Western blotting against the fusion tag could be used to detect the produced protein. The 5’ and 3’ UTR regions of the mRNAs can also show variations and thus, can determine the translation efficiency and stability of the mRNAs. Tassone et al. have shown the existence and usage of different transcription start and end sites in the Fmr1 mRNAs isolated from mouse and human brains (

c. Functional characterization of the protein isoforms expressed from the splice variants: This could be performed by overexpressing each of the splice variants (transiently or stably as required) in neuronal cell cultures (eg. dissociated neuronal cell lines) to check their cellular localization and interactions with other proteins in the cells using pull-down studies, their effects if any, on dendritic spine morphology or on neuronal activity. Differences could also exist with respect to the RNA molecules that associate with these different isoforms of FMRP. Thus, this could also be analyzed using FMRP isoform-specific pull-down or co-immunoprecipitation studies. Similar studies with Fmr1 transcript and isoform expression could also be performed with non-neural and progenitor brain cells (

II. Analysis of the known Fmr1 transcripts and isoforms

a. Identification of the known isoforms of Fmr1: Bonaccorso et al. have shown that the total content of FMRP decreases in the cortex and the cerebellum of the mouse brain during its development and the proportion of decrease varies between the two regions. It was also shown that the total protein content varies between the other regions of the mouse brain as well. The analysis was made using Western blotting with an antibody that recognizes the N-terminus region of FMRP and thus, recognizes its different isoforms (

b. Transcript isoform 7: Pretto et al. have shown that the expression of transcript isoform 7 increases during the development of mouse brain ranging from the embryo to the adult stage (

c. Group C transcripts (lacking exon 12): It has been shown that transcripts of group C are expressed more during the later stages of brain development and amongst the various transcripts been expressed in the cerebellum, they are expressed maximally (

d. Group A (consisting of all exons), B (lacking exon 14) and D (lacking exon 12 and 14) transcripts: It has been shown that the expression of mRNA transcripts for the members of these groups is very low in the different regions of the mouse brain (

III. Elucidating the structure of full-length FMRP

So far, only the structures of the individual domains of FMRP, namely, RGG and N-terminal domains containing KH1-KH2 or Tudor-KH domains are available (

References

-

Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) interacting proteins exhibit different expression patterns during development.International journal of developmental neuroscience : the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience42:15‑23. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2015.02.004

-

FMR1 transcript isoforms: association with polyribosomes; regional and developmental expression in mouse brain.PloS one8(3):e58296. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058296

-

Fragile X mental retardation protein: A paradigm for translational control by RNA-binding proteins.Biochimie114:147‑54. DOI: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.02.005

-

Detection of the 5'-cap structure of messenger RNAs with the use of the cap-jumping approach.Nucleic acids research29(22):4751‑9. DOI: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4751

-

The impact of miRNA target sites in coding sequences and in 3'UTRs.PloS one6(3):e18067. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018067

-

FMRP regulates neurogenesis in vivo in Xenopus laevis tadpoles.eNeuro2(1):e0055. DOI: 10.1523/ENEURO.0055-14.2014

-

The FMRP regulon: from targets to disease convergence.Frontiers in neuroscience7:191. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00191

-

Isolation and identification of cell-specific microRNAs targeting a messenger RNA using a biotinylated anti-sense oligonucleotide capture affinity technique.Nucleic acids research41(6):e71. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gks1466

-

The trouble with spines in fragile X syndrome: density, maturity and plasticity.Neuroscience251:120‑8. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.03.049

-

Fragile x mental retardation protein regulates proliferation and differentiation of adult neural stem/progenitor cells.PLoS genetics6(4):e1000898. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000898

-

Searching the coding region for microRNA targets.RNA (New York, N.Y.)19(4):467‑74. DOI: 10.1261/rna.035634.112

-

Human FMRP contains an integral tandem Agenet (Tudor) and KH motif in the amino terminal domain.Human molecular genetics24(6):1733‑40. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddu586

-

Differential increases of specific FMR1 mRNA isoforms in premutation carriers.Journal of medical genetics52(1):42‑52. DOI: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102593

-

Alternative splicing of exon 14 determines nuclear or cytoplasmic localisation of fmr1 protein isoforms.Human molecular genetics5(1):95‑102. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/5.1.95

-

Differential usage of transcriptional start sites and polyadenylation sites in FMR1 premutation alleles.Nucleic acids research39(14):6172‑85. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkr100

-

Fragile X mental retardation syndrome: structure of the KH1-KH2 domains of fragile X mental retardation protein.Structure (London, England : 1993)15(9):1090‑8. DOI: 10.1016/j.str.2007.06.022

-

Crystal structure reveals specific recognition of a G-quadruplex RNA by a β-turn in the RGG motif of FMRP.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America112(39):5391‑400. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1515737112

-

Transcriptional and functional complexity of Shank3 provides a molecular framework to understand the phenotypic heterogeneity of SHANK3 causing autism and Shank3 mutant mice.Molecular autism5:30. DOI: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-30

-

Identifying microRNA targets in different gene regions.BMC bioinformatics15 Suppl 7:S4. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-S7-S4